On a cool Saturday morning in March 2000, Lewis Gravitt and his wife, April, were arguing in their Chattanooga home. Things were so bad, they were seriously considering going their separate ways.

He was a very angry man, she said later. You never knew when he would snap and hurt someone. "Sorry" was just not enough anymore.

But Gravitt knew where his anger came from; he had known for 11 years.

"Sit down," Gravitt told her that morning. "What I'm fixing to tell you, I don't know how you're going to take it or what it's going to do, but what I'm fixing to tell you I've never told anybody."

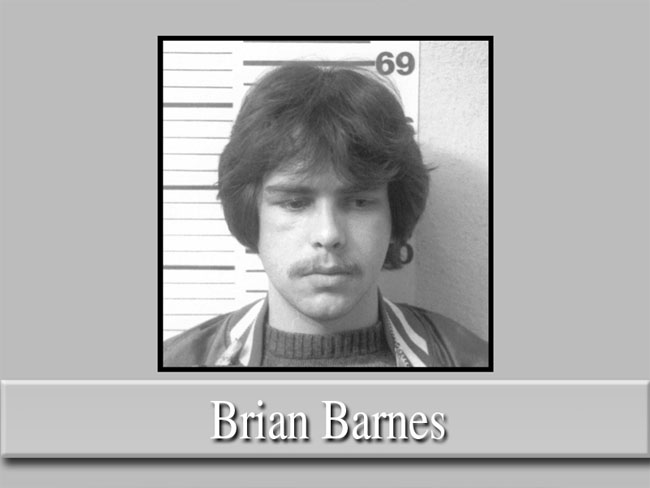

"Do you remember Brian Barnes?" he asked her.

"Yeah," she said.

One of April's friends had dated Barnes in the mid-'80s. They all used to hang out together.

"I'm the one that killed him," he said.

Police didn't even know Barnes was dead. All they knew was he was missing and had been since 1989.

The same day that Gravitt confessed to his wife, Walker County Sheriff Steve Wilson received a cell phone call as he was leaving a funeral.

"I just got to meet with you," Ray Biddy, a long-time acquaintance, said on the other end, urgency in his voice. "I have a man here ... who is telling us about a murder he committed about 11 years ago and he's wanting to confess to you and only you and, furthermore, he wants to take you and show you where he buried him."

For Wilson, it sounded unbelievable.

"Eleven years after a murder, how often does someone come forward and confess to it without being prodded, especially then go and actually prove there's a body there?" the sheriff asked, sitting in his Walker County office for a recent interview.

"It was a very strange meeting," Wilson said. "Maybe that's one-in-a-career type of thing."

* * * * *

Inside a small gray room, Gravitt works for hours at a time, thinking, measuring, cutting and gluing.

The Paperman - as everyone knows him - sits on a white plastic chair with his supplies on a plain plastic table.

He has soft blue eyes behind bifocals, short hair and a trimmed mustache. Tattooed unicorns and skulls start at his wrists and disappear under his shirt sleeves. As he holds the safety scissors it's easy to notice the faded, tattooed letters on his fingers, but they're hard to read. Gravitt said they're something he would get rid of if he could.

With callused, dry hands, he takes a paint brush, dips it into a red Folger's plastic can filled with Elmer's glue, then spreads the glue out on cardboard, before he adds a layer of brown paper. He explains that it hides the corrugation of the cardboard, making it easier to give it the texture needed for the life-size deer or parade floats he makes for nonprofit groups and schools.

His creations border on the extraordinary. A spinning tabletop carousel, each horse striking a different pose. A Noah's ark about 3 feet long, the animals two by two, no bigger than a thumb and finely detailed. A full-size upright piano, so real-looking you're tempted to walk over and play.

For Gravitt, 46, folding and twisting the paper not only allows him to make something beautiful. As he glues and paints and designs, he also travels.

Sometimes he sticks close to home and goes fishing or hunting in Ellijay, Ga. Sometimes he lets his imagination fly and visits places that have never been or real places he may never get to see.

Because as soon as he leaves that room, the Paperman is again inmate 460297 at Hays State Prison, a close security facility in Trion, Ga., where he is sentenced to spend the rest of his life.

* * * * *

Moments after talking to Biddy that day in 2000, Wilson got in his car and drove for about 30 minutes to a ranch-style house in Rossville built in the 1960s.

As he walked into the house, through the living room, everything was quiet, as if someone had died.

In the kitchen, he found Lewis Gravitt - Junior or J.R. as friends and family call him - sitting on one end of the kitchen table. Most of Gravitt's family - his mother, stepfather, wife, in-laws and brother - sat or stood near him. Gravitt asked him to have a seat and offered Wilson a cup of coffee.

"If I tell you what I'm wanting to tell you," Gravitt said, "you have to promise you ain't going to put the handcuffs on me."

"OK, we have an agreement," the sheriff said.

Can a person in Georgia go to the electric chair for murder? Gravitt asked.

"They could, but normally there had to be aggravating circumstances to the murder," Wilson said.

Gravitt told the sheriff he was thinking about the killing every night when he lay his head on the pillow and every morning when his feet hit the floor.

They talked for about an hour and, as darkness set in and the temperature started to drop, heading for lows in the 30s, the sheriff decided it was time for Gravitt to prove his story. He wanted to see the body.

A five-minute drive took them to a home on Thomas Drive, named after one of Gravitt's brothers. The home no longer belonged to the Gravitts so the sheriff had to speak to the new owners, explaining what was going on: They needed to look for a body they believed was buried behind the house.

Gravitt leading the way, the group - which included some of Gravitt's family members, the sheriff and other law enforcement officials - walked down a trail into a wooded area. After about 150 steps, Gravitt stopped, looking at one side, then the other. He pointed to a slight indentation in the ground.

They started to dig about 8:30 p.m. The father of a Walker County deputy lived nearby and let them borrow a mini-excavator.

It was getting colder as they began to dig, Gravitt pacing back and forth, fidgety and nervous, unlike the calm Gravitt that Wilson had talked to back at the house.

After a couple of scoops, a piece of yellow fabric popped up. Picking up shovels and picks in the cold, misty rain that had started to fall, investigators dug the rest of the 3-foot-deep hole by hand.

By 1:45 a.m., they had a skull and longer bones, possibly from the legs and arms, a yellow nylon blanket, 11 bullet casings and a confessed murderer behind bars.

"It is my belief that, if Junior Gravitt had not confessed to the murder and showed us where the body was, to this day Brian Barnes would be in that grave and would still be missing," Wilson said. "There's just absolutely no way he would have ever been found."

Gravitt told Wilson he had killed Barnes to protect his family. The motive was never proven, Wilson said, but it's hard not to believe what Gravitt said.

"When a man comes forward and tells you he murdered someone and tells you where the body is at, why wouldn't he tell the whole truth?" Wilson asked.

"The fact remains he did shoot him and did bury his body," he said.

* * * * *

In prison, Gravitt won't discuss details of the murder, although he accepts the blame.

"It's my fault, it's nobody's fault but my own."

He hints about the pressure that steadily built in him after keeping the secret for 11 years.

"I was just through with it," he said. "I did what I did to protect my family. It was an unfortunate situation."

You could say he's in prison on a "voluntary basis," he said.

"This is a small price for me to pay."

Gravitt acknowledged that he made choices in life that brought him to where he is now -- dropping out of school, running away from home, stealing, smoking marijuana and snorting cocaine.

At a time when he was supposed to be playing football and baseball like other young boys, he was working in the hayfields and around the house in Chickamauga, Ga., a community of about 2,000 people at the foot of Lookout Mountain.

"My childhood was taken away from me by the responsibilities that were placed upon my shoulders at such a young age," he wrote in a letter from prison.

But at the same time, those responsibilities taught him a lot, and he came to feel school was in the way. He dropped out of Rossville Junior High School in the seventh grade - and that's when the bad choices began.

He married at 20 and ran away from his responsibilities in Georgia by moving to Texas. His two children, now 24 and 25, still live in Texas. He has watched them grow up through photos.

He divorced his first wife and married April, who already had two children.

Even as a child, he could draw and build things from scratch, a skill that helped when he worked construction in the late 1970s.

Whenever he was depressed or angry as an adult, he returned to those childhood habits. First it was greeting cards, using cardboard from the covers on notebooks. But he made things only to leave them where they lay, serving no purpose.

"I had found myself living a life where nothing else mattered," he said. "I had learned the process of running from my problems only to have them in your face at whatever known destination I arrived at."

Sometimes that destination was prison. In the '90s, he spent four years behind bars for attempted armed robbery, missing the chance to see his father one last time before he died.

Prison "cost me everything in life," he wrote.

* * * * *

In the summer of 1989, 25-year-old Lewis Gravitt pulled his motorcycle into a Golden Gallon in Rossville, needing gas. An old friend of his, Brian Barnes, walked up to him, saying hello, asking for a place to stay the night.

He and Barnes had known each other for a long time. At one point they were neighbors. They ran with the same crowd and were friendly, so Gravitt didn't think twice about letting him crash at Gravitt's parents' home in Chickamauga.

The men rode off across the state line to Soddy-Daisy, to the home where Barnes was staying. There, Gravitt waited outside while Barnes grabbed his clothes, coming out with a small, black duffel bag.

Once they were back in Chickamauga, Gravitt set up a tent for Barnes behind the house because he knew his mother didn't like having people stay over.

Barnes told Gravitt: "I want to show you something."

From the black bag he took out a big stack of money - $150,000 - and a bag of cocaine.

"Man, what did you do? Where did you get that?" Gravitt asked.

"I got it from where you took me to get my clothes," Barnes said, but his attitude belied his concern.

Barnes made several phone calls. He told Gravitt someone already was looking for them and they had to leave. Gravitt didn't know what to do or what to think, so when Barnes suggested Florida, he agreed.

During their time in Florida, they did odd jobs. Before they even had left Georgia, Barnes had gotten rid of most of the money; only about $4,000 was left. Gravitt didn't know what Barnes did with the cash and never asked.

A couple of weeks later, the pair rode back to Georgia because Barnes said he was due in court in Hamilton County, although he never went.

About two months passed, and Gravitt stopped worrying about the drugs, the money and the men who were supposedly after them. He chalked it up as just one more headache that came with the lifestyle he still couldn't clean up. But it was over and done, he thought.

He was wrong.

Gravitt was outside his house when a car pulled into the driveway. He didn't think much of it because people often used the driveway as a turnaround, but the car stopped and a man got out.

"I've been looking for you," the man said, according to court testimony and the sheriff. He was heavyset, wearing a suit and looked to be in his late 40s.

"Who are you?" Gravitt asked.

The man ignored the question. "Where's Brian?" he asked.

"He's right down there, but who are you?" Gravitt repeated.

Another vehicle pulled up and the doors flew open, a group of men swarming out. They soon had Barnes and Gravitt in the cars, driving to an unknown house.

Once there, the men tied Gravitt and Barnes up, demanding to know where the money was, where the drugs were. They beat them for the information.

Barnes didn't talk. Gravitt didn't know.

"I didn't mean to get you mixed up in this," Barnes said while they lay there, tied up and bleeding.

"It's too late, you know," Gravitt replied.

The man in charge told Barnes and Gravitt they had two weeks to come up with the money - the original $150,000 plus $100,000 for the cocaine.

Barnes called everyone he knew, trying to come up with the cash. They managed to scrape up several hundred dollars.

A couple of days before the due date, the men repeated their routine, including the beatings. Only this time they had a recent photograph of Gravitt, his brother Michael and mother, JoAnn, taken outside their home. They shoved the picture in Gravitt's face and said that's where they were going to start if they didn't get the money.

Gravitt snapped.

"Man, I ought to kill you my damn self for getting me in this," he said as he turned and looked at Barnes.

"That'd be the only thing that would convince me that you are telling the truth that you didn't have anything to do with it," the man in charge told him.

They were let go again, but for Gravitt it was more than his own life on the line. They headed back to their tent behind Gravitt's mother's home.

"You wasn't really serious back there, was you?" Barnes asked as they sat inside the tent, plotting their next move.

"We just need to find a way out of this; we need to find a way out of this," Gravitt told Barnes.

Gravitt knew it was impossible to get the money in time and he couldn't run away without taking his family with him, something else that was impossible. How would he explain? Where would they go?

He left the tent and headed for the house. Inside, he pulled his grandfather's .22-caliber Remington from its case. The family rifle had been passed down to his father.

Back at the tent, Barnes lay inside, propped on his side. When he saw Gravitt coming, rifle in hand, he started to sit up.

"You know we can't come up with the money, and you know what they're going to do," Gravitt said.

"Yeah," Barnes said.

"I'm sorry, man. I'm sorry," Gravitt told his friend. Then he fired the rifle seven times, each shot ending with a click as he let go of the trigger.

He shot Barnes in the head and upper torso, but as he headed back to the house something told him Barnes was still alive. Gravitt reloaded and put another seven bullets into his 23-year-old friend.

No one was at home at the time and no one else heard the shots, or if they did, they never said anything.

At some point, the men had been given a phone number by the leader of their abductors, a way to get in touch. Gravitt dialed the number and, about an hour later, the man in the suit showed up.

Holding a gun, he walked to the tent and peeked inside, poking Barnes' body with his foot. He turned to Gravitt and pulled out the photos of his family, looked at them, then put them back in his pocket.

"I'm going to keep these for future reference," he said.

"What future reference?" Gravitt asked.

"Future reference - you don't know me."

"I don't know you," Gravitt said.

The man got in his car and drove away.

Eleven years later, testifying in his own defense at his trial, Gravitt never identified the man. He said he had never seen him before and couldn't remember his phone number or the location of the house where he and Barnes were taken. Even if he did, he said, he wouldn't tell.

"He got in his car and left. Last I've seen, last I've heard from them," he told investigators. "And I'm laying here with a body, that I just took this man's life away from, and I've got to get rid of this body and I don't know what to do."

* * * * *

It took 11/2 hours in 2000 to select the jury that eventually found Gravitt guilty of murder, felony murder, aggravated assault, possession of a weapon during the commission of a crime and concealing the death of another in 1989.

On Dec. 7, following the two-day trial, the judge sentenced him to life plus 10 years in prison.

His wife, April, didn't want to testify and wasn't forced to.

Barnes' mother was dying of cancer at that time, but his sister, Victoria Hawley, who lived in Atlanta, was present and testified. On the stand, she said she doubted they will ever know the whole truth.

"I guess all we have is his word and whatever evidence is presented, but I don't know that I'll ever know the full story," she testified.

Hawley visited Gravitt in jail and wrote to him. She forgave him, she said in court, but it didn't mean she was OK with it.

And she didn't hate him for it.

"Hate and anger don't bring my brother back, and so I've tried very hard to find a way to deal with all of this. And trying to forgive him is one of the coping mechanisms I've tried to use because I've learned that when you hate someone and you're angry with them, it doesn't hurt them, it hurts you." she said during the trial.

* * * * *

When Gravitt started to serve his life sentence in Hays State Prison, he didn't talk to anyone and kept to himself. He just wanted to serve his time and survive.

In prison, he returned once again to his childhood ability to make something out of anything.

"He has always been artistic; he always worked with his hands," his sister Ceci Ledford recently said as she toured the Victorian Christmas displays in Summerville, Ga., that her brother helped make with other inmates.

He knew wood would be hard to come by in prison, so he thought of nothing more than paper.

About six years ago, while he was working inside his cell on an art project, a woman yelled his name.

At the other side of the hall was LeThicia Davis, a counselor at the prison who was told by a guard she needed to recruit Gravitt for an art program she was starting at the prison. The Faith and Character-Based Program was designed for inmates who want to change, and a component of it is art.

Initially, Gravitt refused to participate.

He was a man who had a problem with authority and a problem with people, a life with no purpose and a life sentence. He had no plans to stay in the program.

In the end, he lost to the power of the woman's persuasion.

As he worked in the program, he began to realize he was just the type of person officials were trying to help, the type of person who had problems dealing with the real world, who would wind up back in prison if he ever got out.

That's where the old Lewis Gravitt met the new Lewis Gravitt.

"This is where things started to matter to me again; this is where the separation of the old Lewis Gravitt, the one with no purpose in life except to do his time, became the new Lewis Gravitt, with a lot of purpose in life," he wrote.

* * * * *

During the six years Gravitt has been in the arts program, he has received more certificates than he ever did while a free man.

He earned his GED this year at age 46. During that time, he had to put his passion aside, he said, and concentrate on his studies with the help of tutors.

His mother came to his graduation.

She had always said, "Boy, how I wish I had seen you graduate," Gravitt said, and he was able to dedicate that day to her.

His family believes he killed Barnes because he had no choice.

"It's not something he wanted to do," said Ledford. "He's had a tough life."

She hopes her brother someday will create art as a free man. He comes up for parole in 2014.

"I just want him out," she said. "I'm extremely proud of him."

Gravitt said he used to talk to his family every week but because of the economy they've had to cut back on the calls.

His son visited him once in prison, but he hasn't seen his daughter in 10 years.

Sometimes he works on projects to get lost, to spend time in his mind with his five grandchildren, whom he has yet to meet.

To feel closer to them, he created a bright red board game. Teach-N-Play is a Monopoly-size board game that teaches children the names of the planets, the numbers, colors, how to save money. The game was invented and made by Gravitt.

He said a wealthy man offered him a lot of money for the game but Gravitt turned him down.

"For me, it's priceless," he said. "I made it for my grandbabies; it is not for sale."

In prison, Gravitt turns the pages of a brown photo album. He takes a picture of every project he works on and, when the album is full, he sends it to his family.

He can look at a picture and remember how he felt when making the artwork, remember where he escaped to in his mind. He might have been at Disneyland or talking to his grandkids.

When he creates art, Gravitt can spend time with his children, his sisters, his brothers. Because as he meticulously turns paper into art, he's no longer a prisoner, at least in his mind.

Staff writer Alison Gerber contributed to this story.

Learn more about the arts program at Hays State Prison

Follow Perla Trevizo on Twitter

EDITOR'S NOTE: Parts of this story about the crime and events leading up to it were taken from Walker County Superior Court records and Lewis Gravitt's interview at the Walker County Sheriff's Office on March 20, 2000. Gravitt's wife, April, declined through a relative to comment.