John Edwards III combed through archives to find information about black soldiers in the Civil War, but a frustrating thread ran through everything he saw.

"Most of the information started off with 'very little is known,' so our position was to help make it known," he said. "When people have done so much and fought so hard to get where we are -- and then to not take advantage of that -- is a slap in the face to people who contributed."

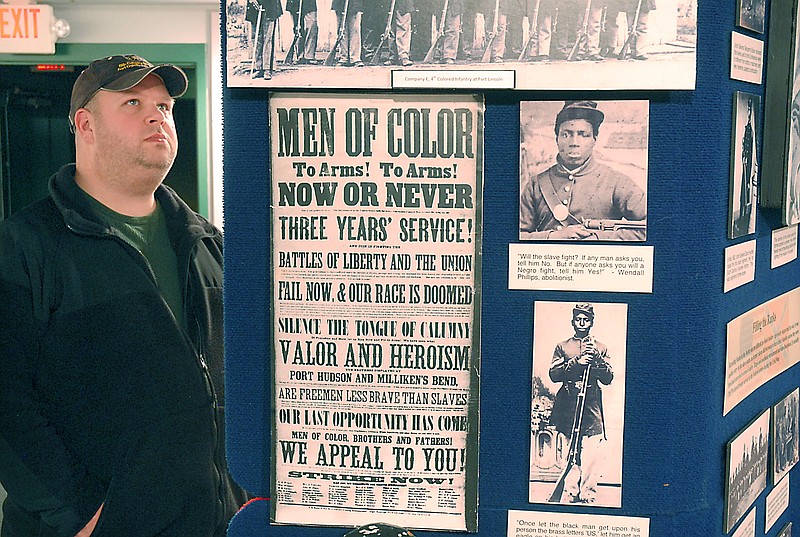

Fifteen years ago, Mr. Edwards, curator at the Mary Walker Historical and Education Foundation, started the research project with his father. The culmination of his efforts is on display as a temporary exhibit at the Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park in Fort Oglethorpe, Ga.

According to the exhibit, the Union Army did not enlist black soldiers at first, but economic factors prompted officials to change policy early in the conflict.

About 80 percent of the 178,975 black troops who fought with the Union during the Civil War escaped from slave states. While many had jobs burying bodies and harvesting plants, some earned positions as officers and 16 received Medals of Honor.

"There's still a lot that's not known about the black soldiers' participation," said Bill Floyd, a Civil War historian who toured the exhibit. "You never know it all. But you always learn something new here -- the depth of their participation and their involvement in various battles. Obviously, in terms of manpower, they contributed a tremendous amount to the Union Army."

Also featured in the exhibit are black women who helped slaves attain freedom. Alongside photographs of Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth is material on Susan King Taylor, who taught black soldiers of the First South Carolina Volunteers to read and write.

Dozens of striking photographs illuminate the exhibit. In one taken at the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg, a black Union soldier shakes hands with a Confederate infantryman.

Many blacks stayed in the Army after the Civil War to engage in Reconstruction efforts, the exhibit explains. The U.S. Army continued the practice of segregated regiments through World War II.

"African-American history should be a part of the history books, not a separate issue," Mr. Edwards said. "It should be part of American history.

"In the overall timetable, these things happened when other things were going on, and the story needs to be told."