Of the 37 Hamilton County public schools that failed to achieve federal standards this year, 29 fell short because they struggled to educate poor black students, an analysis of test results shows.

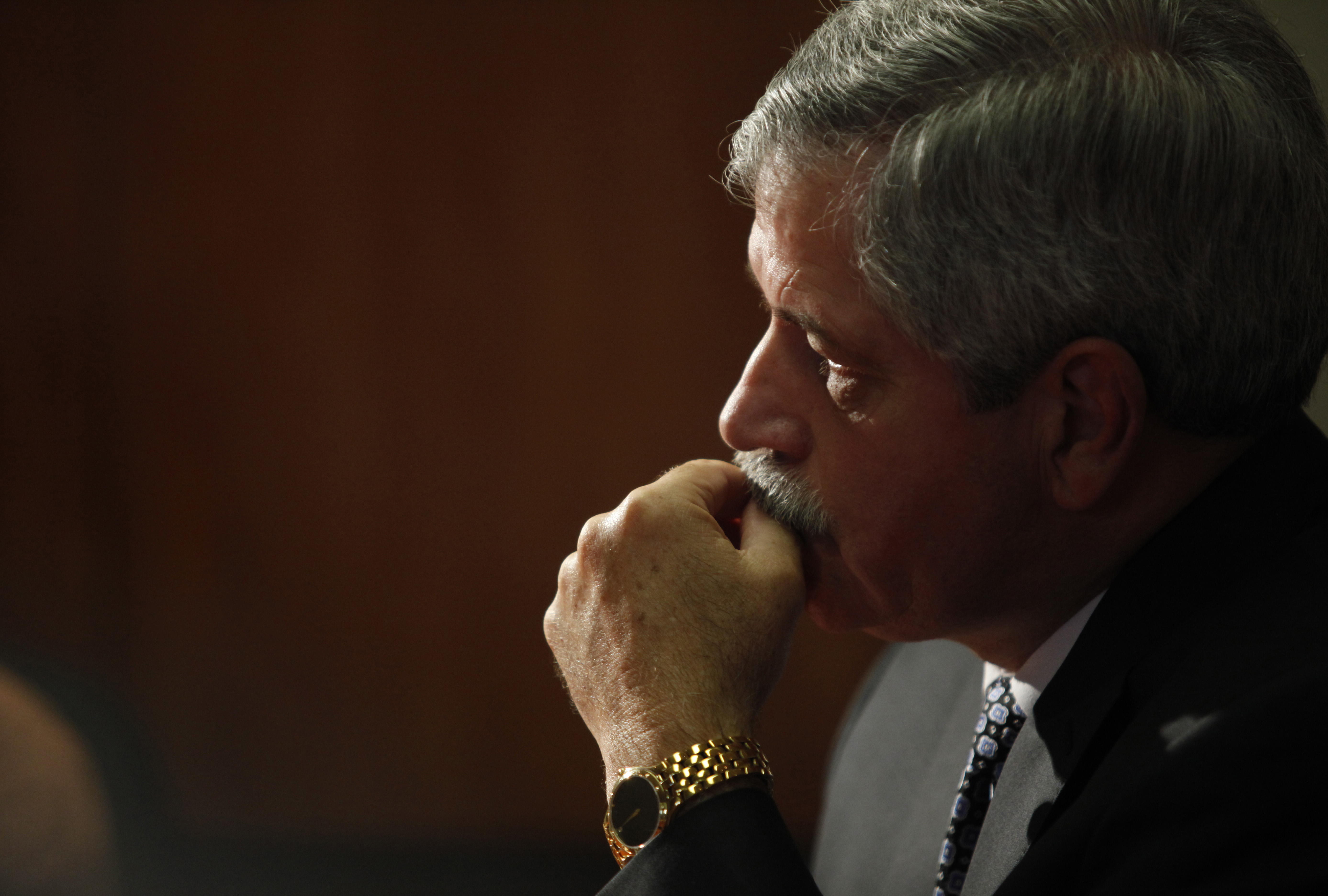

Superintendent Rick Smith said it was those students' test scores that forced the district into a high-priority category, at risk of state takeover if scores don't improve.

Lagging achievement among low-income, minority students is a persistent problem here and elsewhere, one that the federal No Child Left Behind law was intended to address.

Yet despite recent test gains among low-income black students - in preliminary data from the most recent test results, some elementary schools had a 20 percent increase in the number of proficient and advanced students - the county schools still have a long way to go.

"It's clear the schools have made progress, but the gap is there and we have to address it," said Dan Challener, president of the Public Education Foundation, a nonprofit that supports local schools. "A lot of work has to be done."

A Chattanooga Times Free Press analysis of the latest results from standardized tests in Hamilton County Schools also showed:

• Elementary school students outperformed those in middle school, achieving higher proficiency marks in reading and math across the board and having far fewer students below grade level. Only 10.5 percent of third-graders are considered below grade level in math, but by eighth grade that number jumps to 33.9 percent.

• The biggest improvements occurred at the middle school level. The number of students considered proficient or advanced increased 10.4 percentage points among sixth-graders, 9.5 points among seventh-graders and 7.5 points among eighth-graders.

• Although the system made gains in all subject areas, less than half - 44 percent - of public school students are proficient in math. In reading, 45.6 are proficient.

And 20.8 percent of students are below grade level in math, and 14.7 percent are below grade level in reading.

The numbers don't surprise Smith. He didn't expect schools to each produce the required 40 percent of proficient and advanced students in math or the 49 percent of proficient and advanced students in reading. He certainly doesn't expect them to have all children proficient by 2014, as No Child Left Behind mandates.

State officials also call the goals unrealistic. Last week, Gov. Bill Haslam made Tennessee the first state to ask for a four-year exemption until problems with the law are worked out.

BY THE NUMBERS

71: Public schools in Hamilton County37: Number that failed to achieve federal standards19: Number of schools on the No Child Left Behind high-priority list44: Percentage of Hamilton County public school students proficient in math45.6: Percentage of county students proficient in readingSource: Hamilton County Board of Education

"It's getting close to impossible" to meet the federal requirements, said Smith. "It is a tremendous expectation."

Under No Child Left Behind, schools are required to achieve overall goals in the subjects tested. But they also are required to meet them in 18 subgroups.

Being on or off the list of struggling schools can come down to one or two students in a specific subgroup, Smith said.

No Child Left Behind results can amount to a public relations nightmare for schools because it effectively labels schools as good or bad, but Smith said there is an important lesson from the numbers.

Hamilton County school leaders must make literacy, math and leadership improvements a priority if they want to increase the performance of low-income, minority students and make gains overall as a system, he said.

school numbers

Of 39 elementary schools, 16 failed to meet AYP standards. Data from the report show that 14 of those 16 elementary schools failed, in part, because of poor scores in reading or math among economically disadvantaged black students.

Two schools, Bess T. Shephard Elementary and Clifton Hills Elementary, also were flagged for low scores among Hispanic students.

At the middle-school level, Brown Middle, a Title 1 school with a majority of black students, made adequate yearly progress along with Loftis and Soddy-Daisy middle schools. The other eight middle schools did not make AYP because of reading or math scores among black and economically disadvantaged students.

Four of the five high schools that fell short of federal benchmarks were cited for poor scores among black and economically disadvantaged students.

But some are finding ways to reach these subgroups of students.

The key is retaining good teachers, said Challener, whose foundation oversees the Benwood Initiative, a nonprofit that funnels extra money to schools. It trains principals and teachers and works to improve education in 16 inner-city public schools.

Strong principals, professional development, coaching and smaller class sizes have helped Benwood schools retain some successful teachers, even when the pay hasn't been significantly different.

"Teachers are the critical element to student achievement, and we as a community have to attract, retain and train outstanding teachers. The standards have been raised ... the urgency is really clear," Challener said.

Brown Middle School is one place where inroads are being made.

Last year, only 15 percent of Brown Middle's students were considered proficient in math but this year that increased to 35 percent, said Principal Justin Robertson.

Sixty-four percent of Brown's students are on free or reduced-price lunch - a common measure of poverty - and nearly 70 percent are minority.

Robertson said the school has been concentrating on raising test scores.

One of the big changes, he said, was that math teachers started working together more closely.

They met daily to talk about what students were and weren't doing well, and the effort showed that students who traditionally struggle can be reached, he said.

"Too many times teachers go in the room and work by themselves, and we try hard not to do that," he said. "It made a huge difference."

Contact Joan Garrett at jgarrett@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6601.