Antarctic Weather History Lesson Everyone Should Know

Wednesday, December 7, 2011

Departure day! I was very excited to see this NASA image of Antarctica online today. This unique view of the Antarctic Peninsula was taken from aboard the International Space Station. It zeroes in on the exact region we will be visiting. Deception Island is one of the locations we'll be setting foot on - hopefully with similar weather conditions as the astronauts captured in this amazing image. Learn more about NASA's Earth Observatory.

Antarctica's weather is extreme. The coldest reading on Earth was recorded at Vostok Research Station in 1983. An unimaginable reading of minus 128.6 degrees Fahrenheit was obtained by scientists. We have no concept of how cold that is.

My second oldest brother used to live in Fairbanks, Alaska where minus 40 or even minus 50 degrees was possible. I always wanted to visit once during the winter to see if the body can tell the difference between minus 20 and something 20 or more degrees colder.

Thanks to the work of two researchers, we are more knowledgeable about the impact of frigid temperatures.

The man in the image to the right is Charles F. Passel. You probably don't recognize the name, but you are very familiar with his work.

Passel was a team member on Admiral Byrd's third Antarctic expedition. The team left Boston Harbor on a steamer named the North Star on November 15th,1939. The 25 year old Passel signed onto the mission as geologist, his primary task during the next two years was to collect rock samples and map the geologic features in Antarctica.

With dogs and equipment on deck, the crew of the North Star headed south through the Panama Canal, across the Pacific to New Zealand and finally Antarctica. Their journey lasted more than two months.

Passel referred to this expedition as the last of the "romantic expeditions" as they relied on dog sleds and skis for most of their transportation during the nearly two years they lived on the Ross Ice Shelf.

Life was pretty harsh for these explorers. Passel noted that morning temperatures INSIDE would dip to around minus 15 degrees. One of their biggest fears was fire, so the men had to let any heating units go out overnight.

I became acquainted with Charles in 1989 while working as a meteorologist at KTXS-TV. We had a record cold snap that encompassed much of the United States. We were looking for additional stories for our coverage of this arctic outbreak when it was suggested that I go interview Charles Passel.

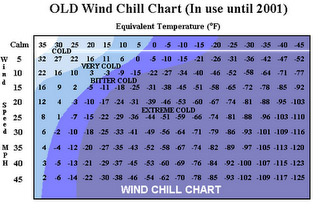

Passel had one other task while on the Byrd expedition: work on the "relative comfort index" with Paul Siple. During the winter night when the men were unable to perform studies away from Little America III, they were given other assignments. Passel and Siple performed more than 400 experiments with a water bottle, thermometer and stopwatch. They wanted to know how fast heat would be removed from an object under certain winds and temperatures. What they were tracking seems like a simple concept, yet until their work, no one had studied this effect since it was first discussed around 1850.

n addition to the water bottle experiments, Passel (seen on the left above) and Siple timed how long it took their faces to freeze under different conditions. Passel estimated they performed these frosty experiments about 100 times. They published their work several years later, mainly for government purposes. The military wanted to know how to protect soldiers in extreme weather conditions. The new "Wind Chill Index" served that purpose. Passel told me once that he had nearly forgotten about this work until a late night ride back to Texas from Louisiana. He was listening to WLS-AM when he heard the disc jockey talking about the Wind Chill Factor. "I knew he was talking about my work," said Passel.

Passel had a wonderful slide show of his time in Antarctica. Three projectors gave everyone the feeling they were actually aboard the North Star or mushing dogs across the frozen landscape. I had the privilege to see his presentation twice. During one program at the Abilene Public Library, Michael Young, the official in charge of the Abilene National Weather Service office, asked a staff member to turn down the air conditioning the night before. The next day the temperature was between 95 and 100 degrees, but inside the room it was about 30 degrees colder. We all felt like we were there with Charles.?

My thanks to Charlotte Passel, Charles' daughter who pointed me in the direction of the Byrd Polar Research Center. Their family donated his original slides to the Goldthwait Polar Library.

Thanks also to Laura Kissel, the Polar Curator of the research center's archival program, for giving me permission to post these pictures. The full collection may be viewed online.

Learn more by reading Passel's book, "Ice: The Antarctic Diary of Charles F. Passel."