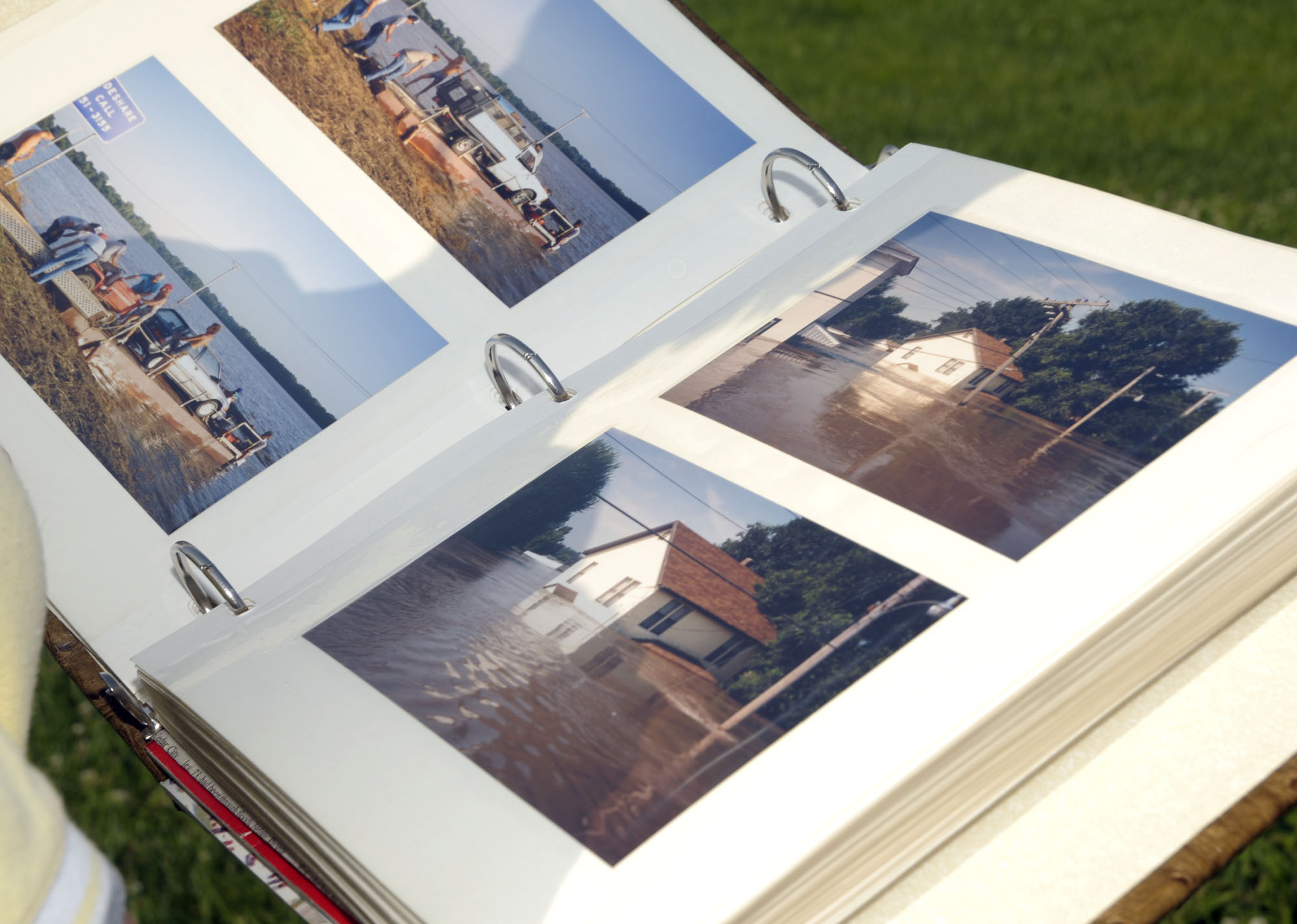

Claudia Boyce holds a photo album of pictures from the flood of 1993 as she stands in the former homestead in Cedar City, Mo. She grew up in the small town of Cedar City, just across the Missouri River from Jefferson City. The Federal Emergency Management Agency has spent more than $2 billion to buy out land in flood-prone areas over a nearly two-decade period. The buyout program launched after widespread flooding in 1993 now has gobbled up almost 37,000 properties, tearing down the homes that were there and prohibiting people from rebuilding. In some cases, entire neighbors and small towns have disappeared as a result of the buyouts. (AP)

Claudia Boyce holds a photo album of pictures from the flood of 1993 as she stands in the former homestead in Cedar City, Mo. She grew up in the small town of Cedar City, just across the Missouri River from Jefferson City. The Federal Emergency Management Agency has spent more than $2 billion to buy out land in flood-prone areas over a nearly two-decade period. The buyout program launched after widespread flooding in 1993 now has gobbled up almost 37,000 properties, tearing down the homes that were there and prohibiting people from rebuilding. In some cases, entire neighbors and small towns have disappeared as a result of the buyouts. (AP)By DAVID A. LIEB and JIM SALTER, Associated Press

JEFFERSON CITY, Mo. - Standing in the front yard of her former childhood home, Claudia Boyce looks across the street to the site of the wooden-framed Methodist church where people had gathered along the banks of the Missouri River since 1878. There's no trace of it now. Gone, too, is her family's yellow, two-story home, the Baptist church to her right, the row of neighbors' homes to her left, even most of the trees.

In their place is mere grass and dirt. The community of Cedar City has vanished - a victim of the great flood of 1993 and a government buyout program that scattered its 400 close-knit residents to higher ground in other towns.

"It's heartbreaking - it just really is," said Boyce, whose memories of the town now are preserved only in a photo album and old newspaper clippings.

Since floodwaters ravaged Cedar City and other river towns in 1993, the Federal Emergency Management Agency has spent more than $2 billion to buy 36,707 properties nationwide, according to figures provided to The Associated under an open-records request. Millions more has flowed to those buyouts through the federal Community Development Block Grant program. The money brought an end to more than 3,000 towns and neighborhoods.

With floodwaters again reaching historic highs this year throughout the Missouri and Mississippi river valleys, Cedar City stands as a symbol of the river's past might and a foreteller of what could become for other small communities from North Dakota all the way south to Louisiana. Although it's too soon to know how many communities may seek new government buyouts, dozens have experienced substantial flooding, including some that until now had escaped disaster.

Another round of buyouts could cost taxpayers tens of millions of dollars. And for the residents relocated, it could cause emotional pains that last a lifetime. In city halls and homes across the country, residents will face the same choice that those in Cedar City did: rebuild or relocate?

The greatest number of buyouts came in the immediate aftermath of the devastating 1993 floods that caused $15 billion in damage and killed 32 people. No state has had more buyouts than Missouri, though the value of its typically modest homes along the Mississippi and Missouri rivers pales in comparison to the hundreds of millions of dollars spent to buy out properties in hurricane-prone states along Atlantic and Gulf coasts.

Many believe it is money well-spent. The buyouts can save government money in a variety of ways, from reduced flood insurance claims to fewer emergency calls and less spent on sandbagging and other flood-fighting efforts, said Sheila Huddleston, mitigation manager for the Missouri State Emergency Management Agency.

"I personally think it's a very valuable program as far as removing people from harm's way," Huddleston said.

Yet for the people who are moved, it can be a life-changing event - and not necessarily in positive way.

The flood and subsequent buyout forced Claudia Boyce's then 68-year-old mother, Lottie Corley, to move into a duplex in a nearby town with her sister whose home also was destroyed. Lottie Corley eventually ended up in a low-income apartment complex before passing away in 2006.

"They were never happy - ever - after that" flood, Boyce said. "My mom, she lost her home, she lost her church and she lost her job. They just never were happy after they had to leave there."

The residents of Cedar City, a former steamboat-stop town located just across the river from the Missouri Capitol, were well-accustomed to floods. When the river soaked the town in the 1950s, 1970s and 1980s, they simply cleared the mud off the floors and repaired their homes, sometimes with federal aid.

But in July 1993, the Missouri River rose higher than ever, with a current so strong it swept the Cedar City fire station off its foundation. At least one house floated away, smashed into a bridge and disintegrated. A 20,000 gallon propane tank, leaking as waters tore it from its base, forced the closure of a highway.

When the floodwaters finally receded, many homes were damaged beyond repair. Jefferson City, which had annexed Cedar City just a couple years earlier, spent $1.7 million in federal funds to buy 162 properties - the vast majority of those in Cedar City.

Now another large round of buyouts seems likely following devastating floods across much of the country this year. The Mississippi River reached near or above record crests from southern Missouri to the Gulf Coast, forcing the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to open long-closed spillways that unleashed a torrent of water over rural homes.

Heavy rains and snow melts also have caused flooding in the upper Midwest, forcing the Corps to release record amounts of water from dams along the Missouri River. That flooding has spread south through Nebraska, Iowa, Kansas and Missouri. Now more small towns - such Lewis and Clark Village and Big Lake, Mo. - are inundated with floodwaters while other places such as Hamburg, Iowa., are hoping that levees hold up.

Larry A. Larson, executive director of the Association of State Floodplain Managers, said it's impossible to project how many buyouts might occur. Towns that would never have considered one before may have to this year. "There was a lot of flooding in areas that aren't typically flooded," he said.

Larson said local governments are more likely to pursue buyouts if an entire region or neighborhood is open to selling. Otherwise, because land sold in the buyouts cannot be developed, areas with partial buyouts end up with a "patchwork quilt."

In Cedar City, just four houses and a couple of businesses remain. Of the residents who took the buyout, some moved only a few miles away to a town built high on the river bluffs. Others scattered further. Although no longer neighbors, some return each September for a Cedar City reunion at the still-standing Lions Club building. But it's not quite the same. That sense of community cannot be recovered.

"All the people who lived in Cedar, we were just neighbors - we helped each other and cared about each other and visited each other. Anytime you'd go out in the yard there would be a group. I miss that," said Florence Vaughan, 74, whose husband still grows a garden on a plot where their house once stood. They gathered there - for old times' sake - to watch fireworks on the Fourth of July.

----

Salter reported from St. Louis.