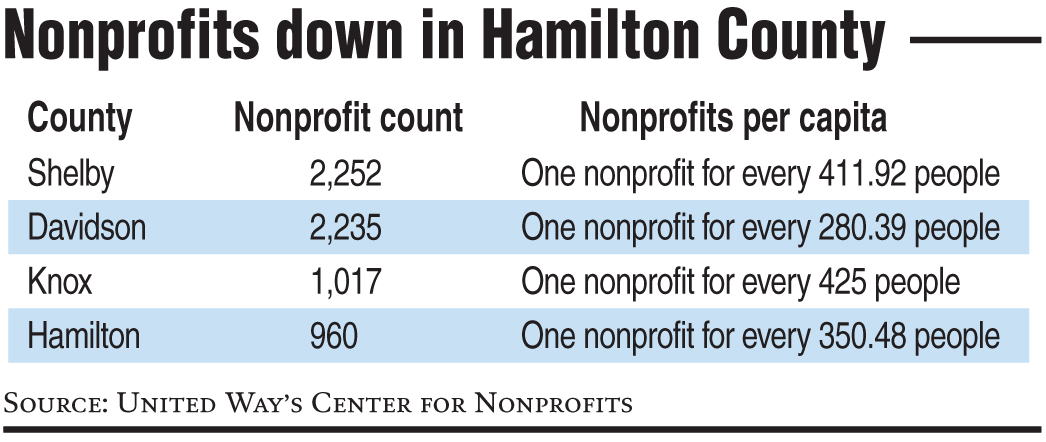

Nonprofit count1. Shelby County: 2,2522. Davidson County: 2,2353. Knox County: 1,0174. Hamilton County: 960Source: United Way's Center for NonprofitsNonprofits per capita1. Knox County: One nonprofit for every 425 people.2. Shelby County: One nonprofit for every 411.92 people.3. Hamilton County: One nonprofit for every 350.48 people.4. Davidson County: One nonprofit for every 280.39 people.Source: United Way's Center for Nonprofits

A shrinking pool of local money is forcing the city's nonprofits to rethink business as usual or close up shop, which hundreds have done.

With as many as 1,800 nonprofits, Hamilton County was once thought of as a Tennessee nonprofit mecca, according to officials at the United Way Center for Nonprofits.

The city's downtown makeover in the 1980s and '90s was shepherded by hundred of millions of private dollars funneled through local nonprofits, and millions more have been pumped into attempts at education reforms, arts resurgence, business recruitment and food education.

That was then. Using Internal Revenue Service data released this year, the United Way Center for Nonprofits discovered there are only 960 nonprofits in Hamilton County and, among larger metropolitan counties in Tennessee, Hamilton now has the fewest total number of nonprofits.

Thirty years ago, Chattanooga had more than half the foundation dollars in the whole state, now it's more like 20 percent, said Pete Cooper, president of the Community Foundation of Greater Chattanooga.

Many of the wealthy families that "funded the evolution of Chattanooga ... will pass (money) to children who don't live here," and may use that money to help nonprofits in other cities, he said. "We aren't going to have the small cadre of rich people to make sure the good projects (in Chattanooga) are funded. It's going to take diverse fundraising ... It's a different ball game."

With less money to go around, some social services in the city have taken a hit. More than 550 families who called the United Way for help couldn't find assistance in the first quarter of this year, according to United Way officials. Eighty-one percent of those calls were for food vouchers, officials said, while many others were for transportation.

Nonprofit agencies provide everything from food to the homeless to afterschool programs for neighborhood children and transportation for the elderly and disabled.

IRS changes

Until IRS guidelines changed in October 2011, no one knew the exact numbers of nonprofits because the IRS wasn't requiring paperwork from smaller nonprofits with less than $25,000 in annual revenue. With the new rules, the new numbers gave a much clearer picture of Chattanooga's nonprofit landscape.

But the IRS rules only revealed what many in the nonprofit world already knew -- these organizations are finding it harder to secure donations because, post-recession, more people are earning less and giving less.

Many nonprofits have gone defunct in the last few years because of lack of funding or inability to file the proper paperwork with the IRS. Some consolidated with other nonprofits to share expenses or avoid service duplication.Community and neighborhood organizations and parent teacher associations have been the hardest hit, said Sheila Moore, executive director of the United Way Center for Nonprofits.

Wayne Owens, transportation director for the Southeast Tennessee Human Resource Agency's special transit services division, said he has seen nonprofits squeezed tighter and tighter in the last decade, and transportation is the first to go. STS financial support has been shrunk by $200,000, or 15 percent, in the last five years, he said.

"The money is not going to be replaced," he said. "Local government can't replace it. That doesn't mean demand has gone away."

Down the chain

Foundations, the agencies that hold most of the money funneled to nonprofit agencies and charities, have struggled, too. Many have reported their investments took a beating during the recession, which gave them less money to hand out.

And well-funded foundations and government agencies are requiring more proof of success before they sign a check over to a nonprofit's cause. Years ago, foundations would approve close to 100 percent of grant proposals, but now agencies are lucky if they get a slice of the foundation pie at all, Cooper said.

Moore said setting standards for nonprofits are important, but those standards can also threaten to run nonprofits out of business. It's expensive to conduct research about whether programs are working. Computer systems that analyze the research data are costly. Researchers are costly. Even background checks for volunteers are costly.

"Nonprofits have to prove it," said Moore. "The big private dollars are changing. Younger generations have changed. In a lot of very wealthy families, that wealth is changing hands."

This year the Lyndhurst Foundation, the legacy of local Coca-Cola bottling magnet Jack Lupton, is changing its structure after 70 years because the family money has been spread out to many out-of-town descendants. Five spin-off foundations will reduce the share of money left in Chattanooga, according to the foundation.

"Forty million dollars is no longer in town. It's not going to be available to Chattanooga like it had been before," said Cooper. "That is the math."

In the meantime, officials with several local nonprofits are looking closely at the big picture in the city, trying to determine if unity among the organizations can do a better job of solving community problems.

The United Way is using a computer program that allows it to map needs in the community based on 211 calls -- a system for social service referrals -- and comparing those spots of need with the actual locations of nonprofit services."It is like a networking across agencies.

It creates a safety net so that it is less likely people will fall through the cracks or use the system in inappropriate ways," said Eileen Rehberg, director of Building Stable Lives and 211 at United Way.

Now that organizers know the total number of nonprofits in Hamilton County, the next step is mapping them out and looking at where their services are located and asking tough questions, she said. Are there too many programs in certain areas? Are there programs that could do a better job of working together? Are there pockets of the community that aren't being reached?

One look at nonprofit afterschool programs showed that children at the Harriet Tubman public housing complex had to walk through high-crime areas to reach the building where the afterschool program was taking place.The data begged the question of whether some of those services should be moved for the children's safety, said Rehberg.

These are the types of problems that nonprofits have to work together to solve, even with fewer dollars, she said.