As bills stack up, poor patients forgo medicines, other care

Friday, January 1, 1904

Dan Cowart sorts through a drawer of medical bills on the front porch of his home on Stringer's Ridge in Chattanooga on Thursday as he talks about his health problems. The bills for doctors' visits and medication to treat conditions such as congestive heart failure and gout, but since he was laid off in 2010 he has been unable to pay them.

Dan Cowart sorts through a drawer of medical bills on the front porch of his home on Stringer's Ridge in Chattanooga on Thursday as he talks about his health problems. The bills for doctors' visits and medication to treat conditions such as congestive heart failure and gout, but since he was laid off in 2010 he has been unable to pay them.Dan Cowart knows what it's like to not be able to pay his medical bills or to skip his medication because he doesn't have money for the prescriptions.

The 47-year-old rifles through a dresser drawer where he keeps the bills -- stacks and stacks of them detailing costs of treating congestive heart failure, high blood pressure, gout, diverticulitis and other conditions.

Cowart, who lives near Stringer's Ridge, was laid off from his job as a maintenance worker in November 2010. He said he is no longer able to work because of his medical condition and has applied for disability.

"There are thousands of people out there just like me, or worse, that can't get the care they need," Cowart said. "It's really sad."

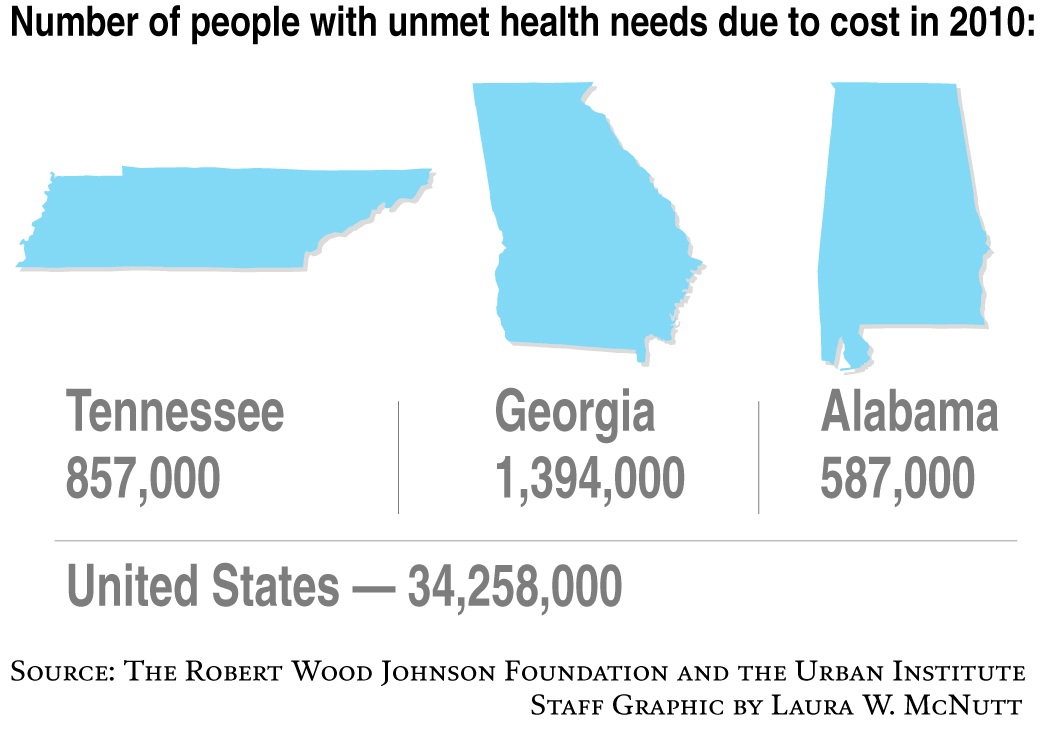

In 2010, about 857,000 Tennesseans and almost 1.4 million Georgians ages 19 to 64 did not receive needed medical care because of cost, according to a study released Tuesday by Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Urban Institute.

In the last decade, Tennessee saw the largest percentage increase in the nation of people -- even those with insurance -- reporting they didn't go to the doctor because they couldn't afford it. Georgia came in third, behind Florida, the study found.

Across the nation, the study found large increases in almost every state of unmet medical needs because of cost, with fewer people having routine check-ups and dental visits. The numbers of uninsured also rose, and those people reported much greater lack of access to care.

"This report is sobering because it demonstrates how profoundly a lack of insurance translates into a lack of medical care, but this report also shows that those with insurance are avoiding care for many reasons, including costs," said Dr. John Lumpkin, with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, in a news release.

DECREASING COVERAGE

The study of changes in medical access from 2000 to 2010 shows that Tennessee, Georgia and Alabama all had increased numbers of uninsured adults ages 19 to 64. Adults in that age range generally are not eligible for Medicaid or Medicare.

Nearly 22 percent of people in Tennessee and Alabama and 24 percent of Georgians in the age range were uninsured in 2010, the study shows.

At 57 percent, Tennessee had the most dramatic increase, rising from nearly 14 percent uninsured in 2000.

Gordon Bonnyman, executive director of Nashville's Tennessee Justice Center, said the sharp increase can be directly linked to TennCare cuts.

"We went, in 2000, from having very broad coverage in TennCare in terms of eligibility and benefits to being one of the most restrictive states in the country in terms of eligibility and what we cover," Bonnyman said.

LOCAL IMPACT

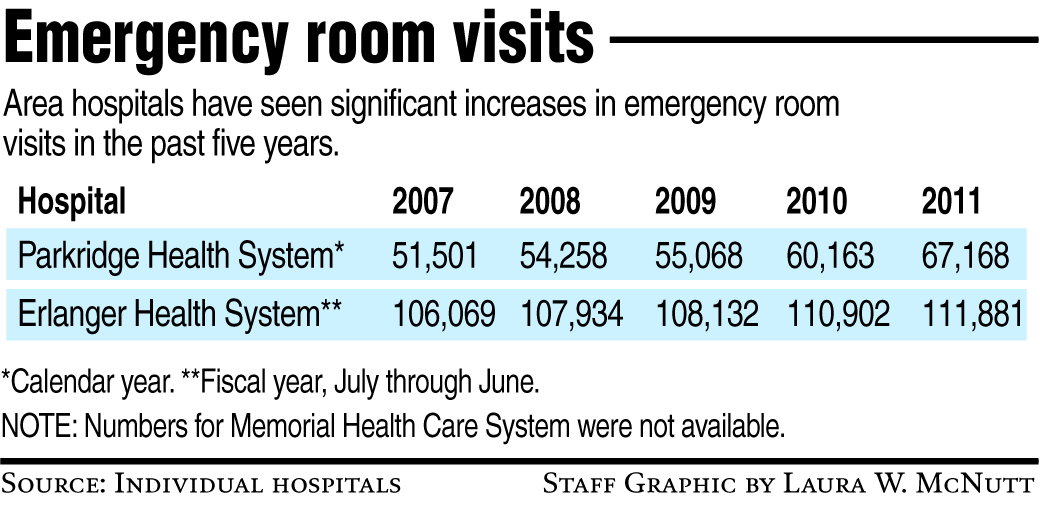

Chattanooga hospital officials say they have seen significant increases in emergency room visits corresponding with the recession and reduced insurance coverage.

"We are seeing a whole lot more people and we are seeing sicker folks," said Dale Solomon, director of the Parkridge East Emergency Department.

By law, anyone coming to an emergency room must be treated, regardless of whether they can pay.

Parkridge emergency rooms saw an increase of more than 12,000 patients from 2009 to 2011, mostly of urgent care patients.

Erlanger Health System also saw its numbers rise over the same time period. Memorial Health Care System's numbers were not available Thursday.

Erlanger is considered the safety-net hospital for the Chattanooga area because it takes the majority of uninsured patients. Its uncompensated care costs rose from $61 million for the first nine months of the 2012 fiscal year to $67 million during the same time period this year.

Solomon said more people are coming to Parkridge emergency rooms needing physician-managed care, making it difficult for emergency personnel to provide the needed treatment.

Hospital personnel make every effort to help patients get prescriptions, access low-cost clinic care or begin regular visits to a doctor, said Robin Marsh, director of emergency services at Parkridge.

Solomon said some people still will return to the emergency room, either because they can't afford other care or chose not to use it.

On Thursday, dozens of Chattanooga area residents shared stories of their own challenges in accessing health care after the Chattanooga Times Free Press posted information about the study on Facebook.

Many described struggling to pay other bills while meeting rising health care costs. Several said they have insurance but can't afford the deductibles.

One woman said she couldn't afford a doctor's visit to get antibiotics and ended up in the hospital with a life-threatening infection.

"My wife and I have insurance and work full-time jobs and still are unable to go to doctor visits," one man wrote.

Cowart said he has been approved for charity care at Erlanger, which helps cut down on costs. He is waiting to see if his disability claim is approved.

"It's such a great nation," he said. "It blows my mind that we let the poor and uninsured just basically die."

Toby Sells, reporter for The Commercial Appeal, contributed to this article.