De facto segregation a threat

Friday, January 1, 1904

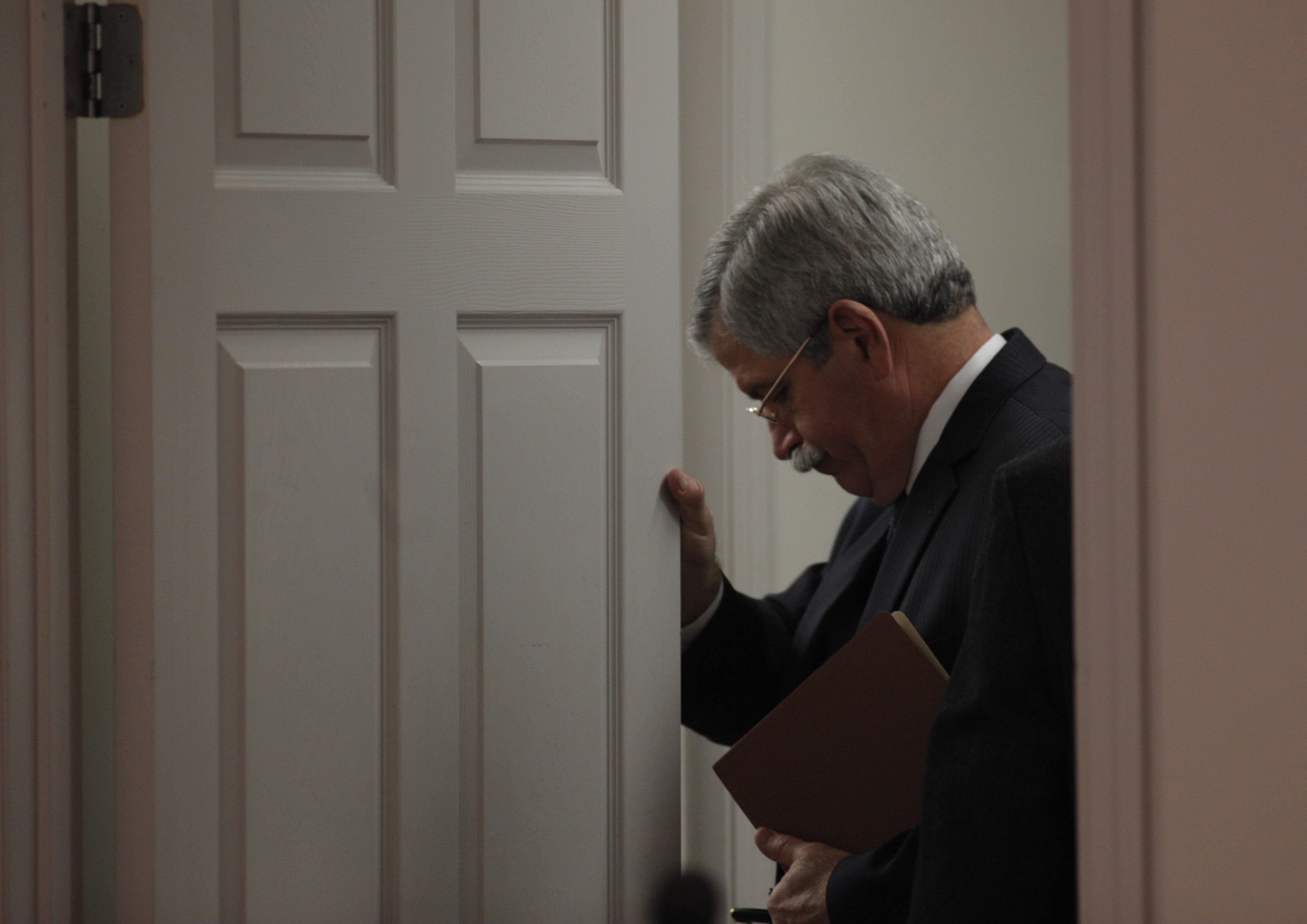

County schools Superintendent Rick Smith's decision -- and the school board's quick approval -- to quit a critical No Child Left Behind (NCLB) program, which let minority students in predominately black schools transfer to majority white schools, is deeply discouraging. It reflects a huge mistake in judgment and a callous backward shift toward de facto segregation. It also denies a safety valve for students who want out of so-called "failing" majority-black schools.

Yet the decision to abandon the program went down 10 days ago over the criticism of board's helpless minority members, and without a ripple of noticeable public controversy.

Contrast that with the attention given the case of five Signal Mountain High teachers suspended for having quiet drinks away from the students whom they were chaperoning on a graduation cruise in the Caribbean. Smith's subsequent vengeful suspension of the school's retiring principal, Tom McCullough, apparently to settle old scores, stirred even more controversy -- more than even Smith's overhaul of principals' positions.

An inherently racist drift

By comparison, the Signal Mountain issues are overblown. It is Smith's drift toward neglect of de facto segregation that needs serious long-term scrutiny.

Smith's decision to terminate the minority transfer program comes on the heels of his recent failure to submit a timely and well-considered proposal for a state Innovation Zone grant that was expected to provide around $8 million or more to help the school system improve performance at seven failing schools, all of which have largely black student populations.

(We use the state's term "failing schools" guardedly. In all too many cases, schools are labeled as "failing" when too many students do poorly not because of failing teachers and curriculum, but because of students' lack of early education in impoverished homes before kindergarten and later, and inadequate resources for teachers.)

Nashville's school system, now headed by former Hamilton County schools superintendent Jesse Register, won an Innovation Zone grant of $12.5 million. Memphis, also the beneficiary in 2009 of a $90 million Gates Foundation award for education reform, received more than $14 million under the Innovation Zone grant. Smith, by comparison, got a $600,000 grant intended to help him and his administration develop a meritorious Innovation Zone proposal in the hope of a future grant.

Hamilton County's mostly black schools, however, need as much help as those in Memphis and Nashville, and they need it now to avoid a state takeover of failing schools. Had he cared more, Smith would have made the Innovation Zone grant application an urgent priority: He would have hammered out a good grant proposal, and he would have gotten it to the state before the deadline.

And he certainly would not have moved so quickly to take advantage of the state's recently awarded NCLB waiver to phase out the minority-to-majority transfers. That he did prompts worry that Smith not only wants to save the transportation costs attached to transfer program. There's also talk that he may cut the special-instruction and after-school programs in mainly minority schools in order to divert those programs' federal funds, which is coveted by the school board's current regressive majority, to the suburban white schools those members favor.

That sentiment reflects the resurgent division of board members and school administrators who have long resented the merger 15 years ago of the city's urban school system into the then-mostly white suburban county school system.

Hamilton County is not unique in this regard. A drift back to de facto segregation has grown in many school systems since the U.S. Supreme Court's conservative majority ruled five years ago that school systems, having moved past the era of busing to achieve integration, did not have to give parents of minority students a choice on the schools they attend.

That decision has not only fueled re-segregation. It also has generated the revival of the segregationists' mindset that "separate but equal" -- under the banner of "neighborhood schools" -- is both feasible and OK, and that teachers' skills alone in mainly black schools can offset the cultural value, to both minority and majority white students, of integration.

Research has long disproved that subterfuge of racism. Broad studies of this nation's history of segregation, integration and educational disparities show that students of both races in integrated schools are typically higher achievers in school and in their subsequent careers than those educated in segregated schools.

'Separate' is never equal

In addition, it shows that "separate" is never equal, especially in communities -- like ours -- where minorities are traditionally poorer, and their schools have fewer resources because students' parents don't have the money, the political influence, the resources and the educational background found in more affluent and largely white communities. So their segregated schools simply cannot keep pace with the mainly white schools in more affluent areas. One need only look at the disparities between the ample financial support of white schools and their communities on Signal and Lookout Mountains and in East Brainerd, versus schools in Alton Park, Avondale, Eastdale and Eastside, to see the disparities.

That is the problem here, and it's always been this community's problem. Now that the county school board has finally gotten a majority of members, and a superintendent, who seem to think separate schools and de facto segregation are OK, the county school system needs more alert scrutiny than ever to assure that equal access to excellent education is a reality, not a hoax.