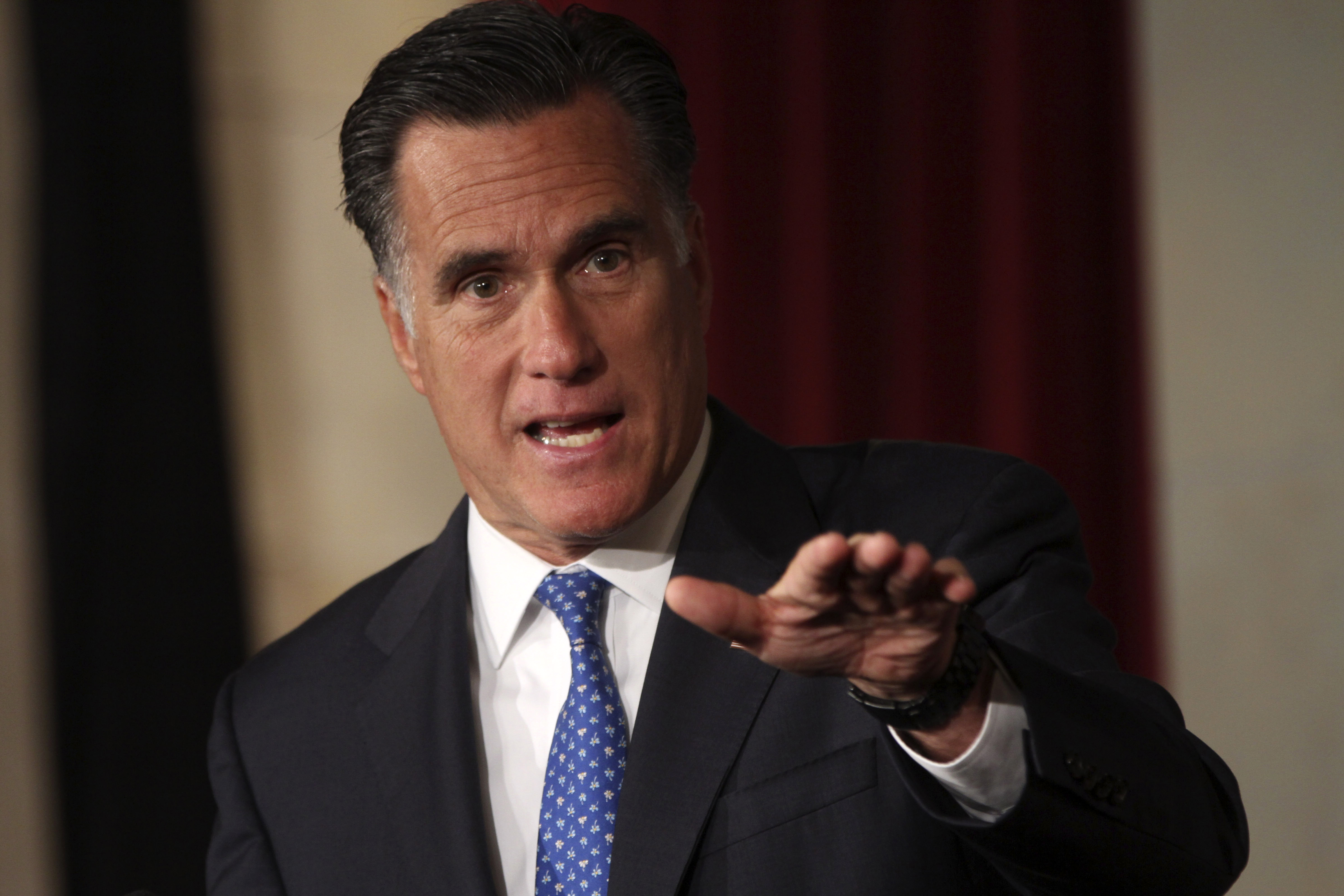

Now that the Texas primary has given him enough delegates to lock up the Republican presidential nomination, Mitt Romney is sure to pivot further away from the divisive social issues and tea party extremes that he embraced in the primaries, in favor of more centrist issues likely to resonate with independent voters.

He's already shifted focus to economic and defense issues, inflating his job credentials while blaming President Obama for problems that Republicans have either induced or would exacerbate. Regardless, Romney's parade of political flip-flops on social issues in the primaries and his personal history as a mercenary venture capitalist at Bain Capital, where he destroyed jobs while raiding pension funds and assets of some of the companies he purchased and bankrupted through leveraged buyouts, taint his claims to be both a courageous leader and the nation's prime job creator.

Romney's promise to mark the first day of his presidency -- if he wins in November -- with an immediate move to repeal Obama's health care reform law is emblematic of his legendary flip-flops on important issues. It also speaks volumes about his apparent lack of concern about the runaway costs of health care and the lack of care for uninsured and under-insured citizens, which are fueling the nation's immense health-care crisis. Yet it was Romney's own health-care reform in Massachusetts, for example, that first invoked a Republican model involving a state mandate requiring individuals to purchase health insurance as a step toward universal coverage.

Romney's Massachusetts health-care reform plan wasn't perfect. It lacked cost control and regulatory oversight of insurance and health-care charges, for instance. But it has worked relatively well in improving access to insurance in Massachusetts, and its advocates are now pursuing implementation of the missing cost controls. But Romney is so anxious to disavow the need for "Obamacare" that he is willing to disown his own success with a similar reform.

He also won't acknowledge that Bain Capital, which he owned and guided as CEO, made a mint for himself and his partners by dismantling and bankrupting some of the 150 companies they bought and sold in the era of highly leveraged buyouts, in which the assets of companies were first used as collateral for the purchase loans, and then often stripped or sold to provide immense profits for the investors.

Research by The New York Times, for example, showed that Romney's Bain Capital earned an eight-fold return on its purchase of an Illinois medical equipment company, Dade, over the seven years it owned the company until its bankruptcy in 2002. In that period, Dade's sales doubled, but its new masters at Bain took in $100 million in fees and compensation, laid off 1,700 U.S. workers, quadrupled Dade's debt, to $2 billion, and then took out $242 million in capital for themselves, pushing Dade into bankruptcy.

The rewards for Bain and its partner investors were stunning. Dade employees affected by plant closings, pension and benefit cuts and layoffs, however, reasonably felt like their jobs and their lives were turned upside down.

Romney still seems insensitive to the damage his company caused to many of companies that Bain Capital bought, reorganized and sold. In the same vein that he boasts of pursuing economic efficiency, he has also suggested that the best route for restoring the damaged housing market is to let home foreclosures "hit the bottom," though that would financially undermine millions of homeowners whose mortgages are under water.

Similarly, he has said repeatedly that he would have let General Motors -- the nation's largest automaker -- go bankrupt in 2010. Inexplicably, he also has criticized Obama for the bailout -- now mostly repaid -- that kept GM afloat while he has also glibly claimed credit for GM's survival -- because it occurred under a form of bankruptcy, albeit a bankruptcy managed and made possible by Obama's intervention.

President Obama's campaign is rightly intent on comparing the president's job as one that looks out for all Americans and the economy's long-term health, as opposed to Romney's harsher path as a venture capitalist for whom multi-million payoffs are the prime measure of economic performance. Obama's recent ad featuring a handful of the 750 Kansas steelworkers who lost their jobs in another bankruptcy generated by Bain Capital irked some falsely righteous Republicans, but it is on point.

"My job is to take into account everybody, not just some," Obama said in response to their criticism. "My job is to make sure that the country is growing not just now, but 10 years from now." Come the November elections, that's a standard that should resonate.