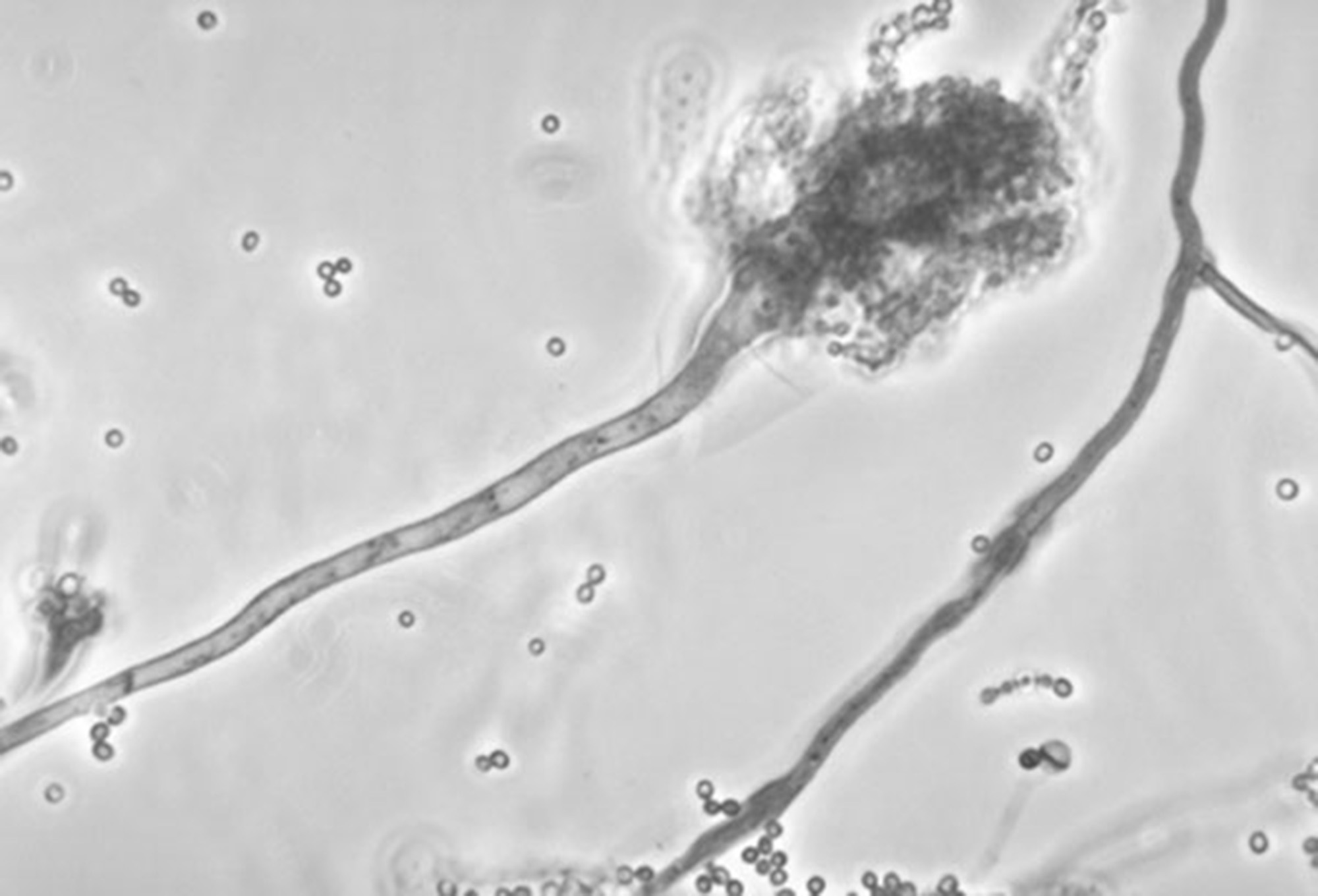

This undated photo made available by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows a branch of the fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. The fungus can also cause skin infections if it enters a break in the skin. The meningitis outbreak is linked to the fungus being accidentally injected into people as a contaminant in steroid treatments. It's not clear how the fungus got into the medicine.

This undated photo made available by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows a branch of the fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. The fungus can also cause skin infections if it enters a break in the skin. The meningitis outbreak is linked to the fungus being accidentally injected into people as a contaminant in steroid treatments. It's not clear how the fungus got into the medicine.WASHINGTON - The chairman of the Senate's health committee pledged Thursday to move ahead with legislation to tighten oversight of compounding pharmacies, amid a deadly outbreak caused by tainted specialty medications.

But a top lobbyist for the compounding industry, and some fellow senators, argued that existing state and federal laws could have prevented the wave of fungal meningitis that has killed 32 people.

In the second hearing on the issue this week, members of the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions sought accountability for the contaminated steroid shots which have sickened more than 460 people in 19 states.

"This committee will forge ahead in developing legislation," said committee chairman Sen. Tom Harkin, D-Iowa. But after more than three hours of testimony from federal and state regulators and industry representatives, there was little consensus on what form new regulations should take.

The International Academy of Compounding Pharmacists' CEO David Miller condemned the New England Compounding Center, the company at the center of the incident, calling it "a pharmacy hiding behind that license and acting as an illegal drug manufacturer."

Miller pledged to cooperate with lawmakers, but stressed that existing state and federal laws could have been used to shut the company down years ago.

"There is no question about who has the authority to immediately shut down an illegal drug manufacturer, and that rests with the FDA," Miller told lawmakers.

Compounding pharmacies, which mix customized medications based on prescriptions, are traditionally overseen by state pharmacy boards. But in recent years larger compounders like the NECC have emerged, mass-producing thousands of vials of drugs that can be shipped nationwide.

That trend has prompted calls for tighter oversight.

Food and Drug Administration Commissioner Margaret Hamburg said her agency needs clearer authority to go after large-scale compounders, who have challenged the agency's authority in court since the 1990s.

In her second congressional appearance this week, Hamburg described a "crazy quilt" of conflicting laws and court rulings that limit the agency's ability to take action.

Hamburg suggested Congress set up a two-tier system in which traditional compounding pharmacies continue to be regulated at the state level, but larger pharmacies would be subject to FDA oversight.

But some senators questioned why they should give the FDA more authority when it did not appear to fully exercise its existing powers. Sen. Pat Roberts, R-Kan., pointed out that the FDA inspected the NECC three times before the latest outbreak and issued a warning letter to the company in 2006, but never shut the operation down.

"Why do we even have an FDA and why do you have a job if the FDA can't stop back alley, large-scale drug manufacturing that it knows about - and writes letters about?" asked Roberts.

Hamburg reminded the senate panel that routine oversight of the NECC is handled by the state pharmacy board, who reported as recently as 2011 that the facility met quality standards.

Sen. Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn., acknowledged the legal ambiguity confronting the FDA, but said the agency has a responsibility to assert its authority in the face of such challenges.

"An enforcer knows that in that situation the only way to protect the public is to use whatever authority he or she has," Blumenthal said.

Congressional efforts to give the FDA more authority over compounders stretch back to the 1990s, and have largely been unsuccessful thanks to vigorous pushback by the compounding industry.

In the most recent attempt, senators including Roberts and Ted Kennedy, D-Mass, circulated a bill in 2007 to give the FDA more power to inspect compounders and set standards for sterile processing of medications.

Roberts recalled Thursday that before lawmakers could even finish writing the legislation, "we were faced with a full-on grassroots effort to stop the discussion draft from moving forward."

"What we needed were more answers, what we got was pushback," Roberts said.

The International Academy of Compounding Pharmacists spent more than $1 million lobbying Congress in the past decade, according to data from the Center for Responsive Politics.