Converting shuttered U.S. Pipe and Wheland plants to commercial, housing space (with video)

Friday, January 1, 1904

Chattanooga's U.S. Pipe and Wheland Foundry site was once a metal city buzzing with thousands of laborers. But the cathedrals to capitalism have since turned to labyrinths of dust and rust.

Today, the ruined buildings at the throbbing Interstate 24 artery provide little aesthetic or economic value to the city, though the stories of the site's heyday still resonate for those who remember them.

Property owners now hope that a recent plan to route the Riverwalk nature trail through the site will provide the spark needed to spur development. Along with Tim McGraw's rowdy music video "Truck Yeah," which was shot on site in August, the recent signs of life have ignited interest in the long-dormant property.

Though the years have taken their toll on the iron parapet of Chattanooga's western gateway, owners hold out hope that the site will become something great. They want more than a waterpark or a Walmart. They want a legacy.

For now, however, the land is still waiting for the right developer, the right tenant and the right lender.

"This is a gateway location for our city that offers the potential for some unique and important development," said Mike Mallen, one of the principals in the real estate partnership that has acquired and cleaned up the industrial site over the past decade. "The events that have transpired in the past two years have made us more positive than where we were in 2008. But we're still waiting."

Forging history

David Giles built the first building of Chattanooga Foundry and Pipe Co. in 1882, constructing the monolithic husk that greets Chattanooga visitors traveling into town from the west. It joined Wheland Foundry - founded in 1866 - in the sooty heart of Chattanooga's industrial hub.

The plants produced pipes, auto brakes, cast iron fittings, valves and hydrants in Chattanooga for more than 100 years. Wheland once produced gray and ductile iron brake castings and drums for nearly half of all vehicles made in North America.

Burdened by ill-timed investments and outsourcing, Wheland shut down in 2003. In 2005, corporate parent Walter Industries announced it would close the U.S. Pipe plant.

Two weeks before Christmas, U.S. Pipe fired 243 of the plant's 345 workers. The remaining 102 drove home for the last time in 2006.

Inside the locked gates, the yellowing layoff notices from 2006 still hang in the dead factory's power station. A clock is stopped at 11:37. Stickers proclaiming union solidarity pepper lockers throughout the facility.

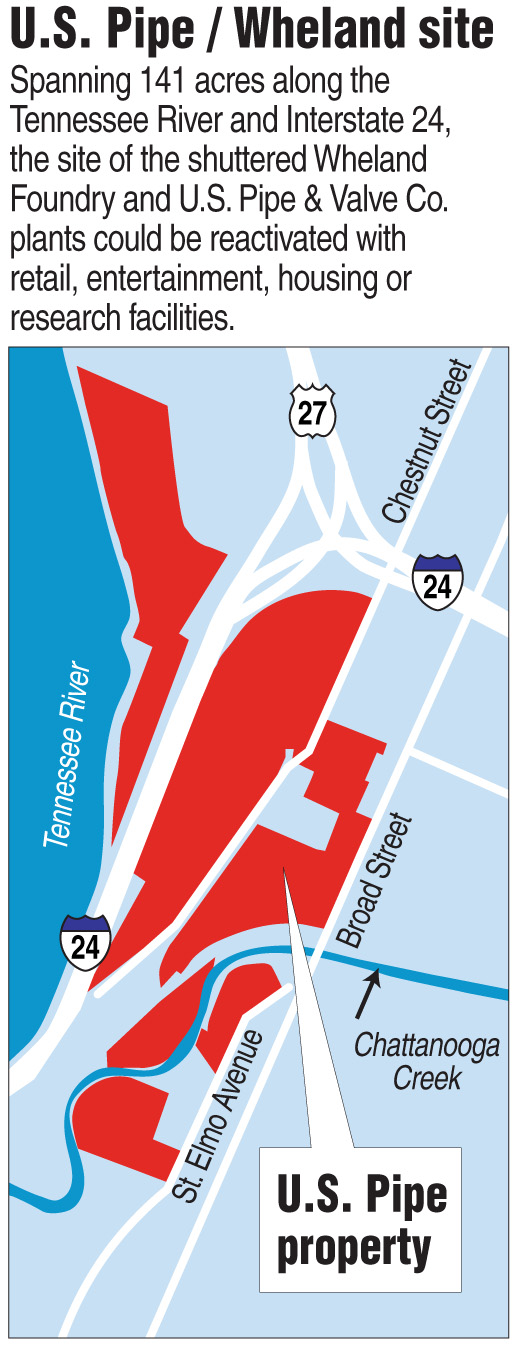

The machines at the 141-acre graveyard have long since disappeared, sold for pennies on the dollar after the plant's closure eight years ago.

A dusty sign in a locked workshop, now visible only to rats and the occasional bird, asks no one in particular where America's children will work if the country continues to import more goods than it makes.

New plans

That's an easy question, if you ask the partners in Perimeter Properties. The children and grandchildren of the plant's aging retirees will work right here, inches from the spot where rows of smelting furnaces once belched smoke into the air.

Chattanooga's next generation will be making change instead of bending iron, breaking rolls of quarters at an enormous live-work-play development that connects I-24 to Broad Street.

Perimeter Properties' 2008 master site plan is aging better than the bleached and cracked parking lots, said Mallen, who still is seeking a master developer to transform the historic ruin.

His plan for rehabilitating the U.S. Pipe and Wheland Foundry tracts was conceived and prepared by a blue-ribbon team including the Lyndhurst Foundation, River City Co., Urban Design Associates and a handful of experts on brownfield redevelopment.

The plan was published in February 2008.

Unfortunately, that was a bad month for real estate. In February, then-President George W. Bush was forced to sign a $168 billion economic bailout - the first of several. Bear Stearns fell apart in March. Countrywide collapsed in June. Lehman Brothers filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in September.

It was not a good year for a mixed use brownfield development, which eventually could cost as much as $1 billion to complete.

"The housing environment we had up until 2008 was very different after 2008," said Mallen.

Housing has begun to thaw this year, and banks claim they're loosening up on loans. The Greater Chattanooga Association of Realtors has reported rising prices and sales.

"There's reason for optimism going into the last third of 2012 and even into 2013, and housing is actually playing a large role in that positive outlook," said Mark Hite, president of the association.

Tentative tenants

In the years since U.S. Pipe closed down, a few tenants have nearly moved in -- but none have committed.

Developers have nixed several plans as being too small. They're waiting for exactly the right tenant to get things started. And they can afford to wait, Mallen said, since he and partner Gary Chazen own the property outright and don't have to pay back a loan.

"Some of the more typical big boxes have been around and asked about building there, and we've declined because we don't want to build the site around a grocery store," Mallen said. "All those kinds of uses have a place on the site but that's not how we're going to kick it off."

Fits and spurts of progress were marked by a reduction in buildings rather than the construction of new ones. In addition to earning a clean bill of health from the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation, Perimeter Properties has demolished several corrugated metal structures and capped a small mountain of foundry sand.

The only sign of life on-site is a facility operated by Motor Wheel -- a distant relative of the Wheland Foundry -- that quietly continues to produce brake drums for heavy-duty trucks. Motor Wheel was bought in April with little fanfare by Charlotte-based EnPro Industries and sits on land not owned by Perimeter Properties.

At one point, Bass Pro Shops sent a real estate executive to meet with Perimeter Properties, but it didn't go anywhere.

"They expressed some interest in the site, we hosted them for a tour, and that's about the time the economy slowed down," Mallen said.

New Belgium Brewing briefly considered setting up its first east coast facility on the site, but ultimately built the brewery in Asheville, N.C.

"We did everything we could to make information available to them, and my understanding is we came in second place," Mallen said.

Even Chattanooga's UTC Sim Center considered moving its supercomputers to the site to create a research hub, pushed at the time by then- Rep. Zach Wamp, R-Tenn. But when hoped-for matching federal and state dollars dried up with the economic downturn, the research park plans fell flat.

"We met with them [Sim Center representatives] and told them we would donate the land necessary if they wanted to do that," Mallen said. "It hasn't happened."

Execution

Yet the dream for a true mixed-use community alongside the Tennessee River lives on in a 44-page plan filled with illustrations and descriptive language. The plan calls for a 525,000-square-foot retail and entertainment development called Foundry Row, which would reuse the historic U.S. Pipe foundry as its main feature. The development would include an urban hotel, streets, sidewalks, park space and surface parking lots -- all highly visible from I-24.

Foundry Row would make a "gateway statement" to cars entering the city from the west, the document's authors wrote, simultaneously showcasing Chattanooga's industrial past and its progressive future.

At the time of publication in early 2008, the master site plan called for 325 hotel rooms, 1,500 dwelling units, thousands of parking spaces, more than 400,000 square feet of retail space and almost 600,000 square feet of office and flex space.

A decaying circular brick building, once used to house drums of oil needed to keep the plant moving, could become a small cafe. A graffiti-filled tunnel that runs under the active railroad tracks could be a public space that incorporates stormwater management features. The trademark foundry would be reused in the style of Chattanooga's First Tennessee Pavilion or Keystone Commons in East Pittsburgh, Pa.

Parks would replace parking lots, and trees would replace trusses.

But before any stores open their doors, the entire site must be cleared of the concrete and rebar jungle criss-crossed by rough roads and railroad tracks.

"Taking down a 140-acre industrial site up until 2008 was challenging but doable. Post-2008, it's just tough," Mallen said.

Since the site is a brownfield, all on-site materials will probably need to be ground up and reused on-site, the developer said. That process alone could cost more than clearing, developing and building on a similar greenfield lot.

"It's a massive, time-consuming and very expensive undertaking," he said.

Despite its frontage along the I-24 western entrance to Chattanooga, the site has no direct highway access and is unlikely to get any exit, according to state highway planners.

Jennifer Flynn, a spokesman for the Tennessee Department of Transportation, said state officials have talked with developers and others about restructuring the Market and Broad streets exit ramp to better accommodate the development. For now, however, "there is no funding in place for the interchange modification," Flynn said.

Takedown

The next step is to find a master developer with brownfield experience and a willing lender to finance the project.

"If you look around the country and around the world at the massive brownfield redevelopments that have been done successfully, they're funded by mutual fund investors and insurance company investors," Mallen said. "There's got to be a very substantial source of capital and development expertise to make it happen."

Things have been quiet so far on that front. But the Riverwalk extension - which is partially funded - could bring new interest to the site.

Sculptures formed out of machinery and products welded in riverside factories will line the Riverwalk, said John Brown, project manager for Barge, Waggoner, Sumner & Cannon Inc.

The 3.5 miles of additional greenspace will meander directly through the center of the project, on land donated by Perimeter Properties. Drawings show the path following the river past Alstom and PSC Metals, then cresting a hill of foundry sand to view a 360-degree vista of Chattanooga's Southside.

Next, the path crosses under I-24 and dives into the heart of the U.S. Pipe site. Eventually, it winds its way to Broad Street, emerging from the Wheland Foundry site behind Crust Pizza.

"Obviously, if we get this 40 linear acres of trail and greenspace and greenway through the site, it is a positive step toward starting to make the site present itself for development," Mallen said. "I still think the right use will find the site."