A judge has ruled that the five emails alleged by a group of residents to contain a record of the Industrial Development Board's hidden deliberations may remain secret because they deal with legal issues.

His ruling is seen by some as a new, more restrictive interpretation of state open records laws, which have allowed disclosure in similar cases.

The handful of hidden records that allegedly reveal the rationale for $9 million in taxpayer financing to a subdivision developer may remain private under the attorney-client privilege rule, wrote Chancellor W. Frank Brown in an 11-page ruling.

"The disclosure of [City Attorney Mike] McMahan's communications to the members of the [Industrial Development Board of the city of Chattanooga] would clearly reveal the substance of the client's confidential communications," Brown wrote.

But his ruling misses the point of an open-records law, said Helen Burns Sharp, who filed a lawsuit to reveal information that she says would explain why $9 million in financing was granted to York Capital to build a road up Aetna Mountain.

"What to me is a little peculiar, is it seems the city attorney should have given them this advice at a public meeting," Sharp said. "They were deliberating toward a decision, it would appear, yet the public can't see these documents."

Sharp and her attorney, Chattanooga-based John Konvalinka, have maintained that the necessary trigger for the Industrial Development Board to approve a $9 million bond offering -- an unqualified opinion from the developer's bond attorney supporting the action -- was never made public.

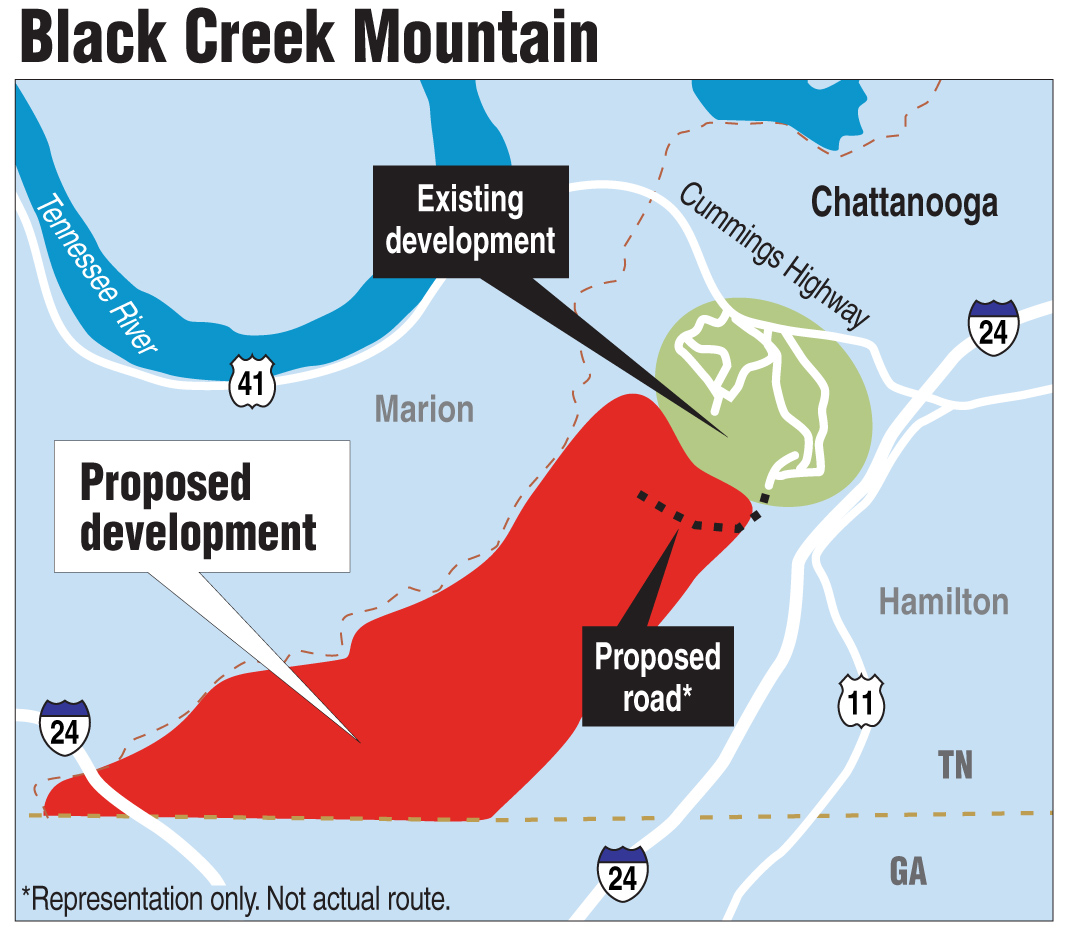

As a result, the public has been unable to judge the rightness or wrongness of the decision to build a road and utilities to the top of Aetna Mountain using tax dollars.

Sharp's request for the records is part of a broader argument that the development should never have qualified for Tax Increment Financing, because it is a residential neighborhood rather than a commercial development.

Tax Increment Financing uses the future increase in a property's taxable value to pay back developers for commercial improvements over a period of years.

"Her basic complaint is that this project should not be a TIF project," said McMahan, who said he was preparing to a motion to dismiss several of Sharp's charges.

Developers have maintained that the sewer pipes which will run alongside the $9 million road qualify Black Creek Mountain as a commercial project, but have declined to comment on the case directly as they are not named in the suit.

Either way, these types of decisions should be open to the public, not made in secret, argued April Eidson, a citizen who has long opposed the Black Creek Mountain subsidy as an unnecessary expenditure.

"I think this ruling is horrendous because what it does is it makes government more secretive, and that's never good for anybody," Eidson said. "They're giving away our money and people can't look."

Like Sharp, Eidson in 2012 made a request for TIF records, and her request was similarly denied under attorney-client privilege. The only difference was that Eidson made her request of County Attorney Rheubin Taylor, not City Attorney McMahon.

Taylor's attempts to keep the documents secret was overruled by Elisha Hodge, open records counsel for the state of Tennessee.

"In order for the attorney work product exception to be applicable, the records maintained by the county attorney have to have been prepared in anticipation of litigation by or for legal counsel," Hodge wrote.

Hodge ordered Taylor to turn over the documents.

Contact staff writer Ellis Smith at esmith@timesfree press.com or 423-757-6315.