I have a dream: For 50 years of gain there still is much to do

Sunday, August 25, 2013

"I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: 'We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal. ...' I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character."

If these words don't make chills run along your spine, you are not human.

Wednesday will mark the 50th anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I have a dream" speech.

The speech, now world famous, was intended to be brief, and nowhere on the three-page, type-written copy that King began reading from that Aug. 28, 1963, day was the word "dream."

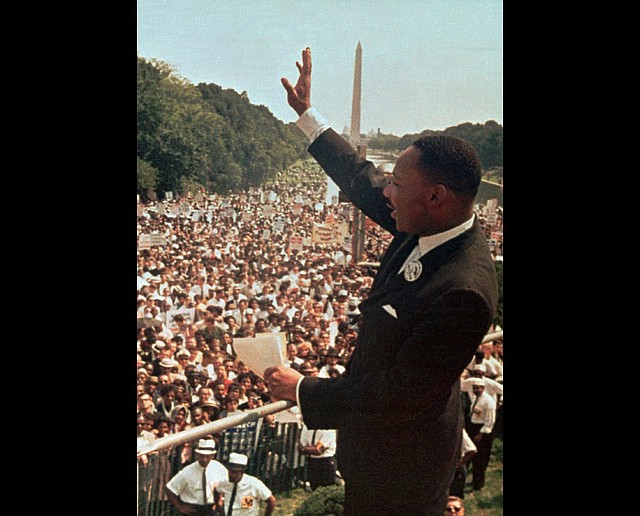

But several minutes in, King stopped reading and looked up to the 250,000 people in front of him and to the skies above. Then he began just talking, preaching, reaching the rainbow of people who had shown up for the March on Washington for jobs and freedom.

He picked up a line that he'd used a week earlier in Chicago; two months earlier at a mass rally in Detroit; and several other times in the previous year, according to historians. But this time, the audience was larger and in a tense capital where troops where massed just outside the city in case President Kennedy had to sign the already-prepared martial-law orders. This time the event was televised. And this time the crowd was electrified.

Still, it wasn't until King's assassination that the speech, offered in front of the Lincoln Memorial, would become immortal. Then, in the words of Drew Hansen, author of "The Dream," a book on the speech, it became "one of those things that we look to when we want to know what America means."

As King spoke, more than two-thirds of the nation's black people lacked the right to vote, to attend integrated schools or to use the same public facilities as whites.

King's speeches and rallies - along with those of many other activists - finally made civil rights the nation's top domestic political issue. That same summer marked 1,122 civil rights demonstrations around the nation and about 20,000 arrests, almost all in the South, according to USA Today.

Now, half a century later, there are clear gains, but not enough.

Only 15 percent of black adults today lack a high school education, compared with 75 percent 50 years ago. Three and half times as many now attend college, and for every graduate in 1963, there are now five. The number living in poverty has declined 23 percent. Those owning homes have increased 14 percent.

But, according to the National Urban League's "State of Black America 2012 report, "almost all of the economic gains of the last 30 years have been lost" since late 2007, and worse, "the ladders of opportunity for reaching the black middle class are disappearing."

In 2010, the median household income for African Americans was 30 percent less than the median income of white households 30 years ago. African-American household income fell more than two and a half times farther than white household income during the Great Recession, 7.7 percent versus 2.9 percent. Black home ownership rates also fell at roughly double the rates of whites, essentially wiping out the gains in home ownership since 2000. And today, more than a quarter of African Americans live below the poverty line, compared to about 10 percent of white people.

Adding insult to injury, the Supreme court last month decided there is no longer a need for the backbone of the Voting Rights Act. Even as justices gutted it, a free-for-all began in several majority Republican states to make it harder for minorities to vote.

We cannot let go of Dr. King's dream. Our dream. Let freedom ring.