Reality check: Lookout Valley ninth-graders learn importance of budgeting

Friday, January 1, 1904

PERSONAL FINANCE MANDATE

Fourteen states require a high school personal finance course:Connecticut, Georgia, Idaho, Illinois, Louisiana, Missouri, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Utah, Virginia and West Virginia.Source: Council for Economic Education 2011 Survey of the States

Ninth-grader Kyle Smith thought he was making reasonable financial choices during a role-playing exercise at Lookout Valley High School on Tuesday morning when bought a Chevy Silverado instead of a Hummer and opted for an apartment instead of a penthouse.

Playing a married advertising specialist with a daughter and a $1,768 monthly income, he thought it'd be easy to pay the bills.

Then he checked his budget.

"I only have $8 left after paying for day care," he exclaimed with dismay, waving his scenario sheet around and bouncing from booth to booth during the 40-minute exercise.

And he still needed to go to the supermarket and buy clothes, he admitted.

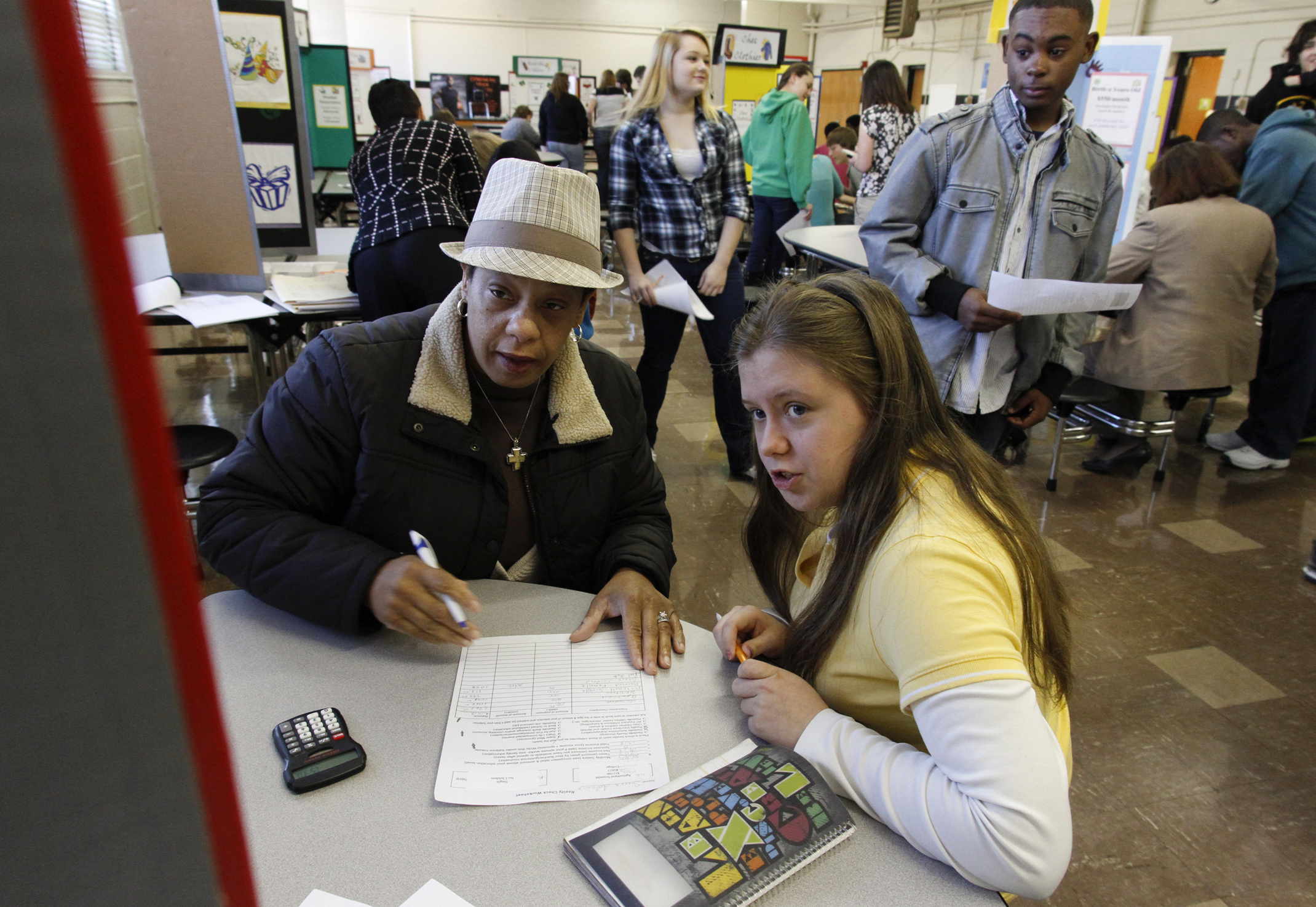

About 50 Lookout Valley High students participated in Tuesday's "Reality Check" exercise, which is sponsored by the Chattanooga Area Chamber of Commerce and aims to give high school students a taste of real-life money management.

His classmates were transformed into secretaries, car salesmen, teachers, graphic designers or high school dropouts, assigned salaries and asked to manage one month's budget.

"The goal is to show students the relationship between education and earning potential," said Mattie Moran, director of workforce development and education for the Chattanooga Chamber. "You find very few students who are financially literate -- this is an eye-opener for them."

It's not just high school students who struggle to handle personal finances: 56 percent of adults admit they don't have a budget, the National Foundation for Credit Counseling reported in its 2012 Consumer Financial Literacy Survey. And more than 40 percent of adults give themselves a grade of C, D or F on their knowledge of personal finance, the report showed.

"You can see that there is a big gap," said Nan Morrison, president and CEO of the Council for Economic Education. "We've lived in boom times for many years. There were two whole generations where the attitude was, 'Finances are kind of interesting, but we don't really have to pay attention because life will always be good: house values will go up, the government will be there to pay for my retirement, my company will be there to pay for my retirement.' So we haven't done a great job with [financial literacy]."

Tennessee and Georgia are two of only 14 states that require high school students to take a course in personal finance, according to the Council for Economic Education.

Morrison said state-required personal finance classes can make a huge difference in students' financial literacy.

"When you have a requirement, things get taught," she said. "And if you put a high-stakes test next to it, teachers get trained and the kids do better over time. But if you don't have deep standards and really good cirriculum and lessons to go with those standards, it's not going to be engaging."

About half the Lookout Valley students made it through Tuesday's scenario with a balanced budget, Lookout Valley instructional coach Bertha Collins estimated.

Across Tennessee, this year's graduating class will be the first class that was required to take the personal finance course to graduate, June Puett, extension agent at the University of Tennessee extension said. The state-mandated course has been well-received, she added.

"One thing I've noticed recently is the interest in personal finance," she said. "The students are seeing their parents suffer with the bad economy and they're realizing why their parents are saying, 'No, you can't have that, or you can't do this.'"

Tenth-grader Lindsey Levitt was a car salesman in Tuesday's Reality Check exercise, and earned $1,903 a month for her spouse and two kids.

"I'm scared for this to actually happen," she said. "My sister has a baby and I see how hard it is for her and her husband to go to college and take care of the baby."

She managed to end the simulation with $314 in savings. She's already taken Lookout Valley's personal finance class, but said Tuesday's exercise was a more grounded experience. She didn't understand everything from the class.

Puett said the state-mandated course isn't without weakness -- it's a half-credit class and teachers often aren't specialized in finance.

"The teachers have had to take on this with, usually, just a two-day training," she said. "It's not like an English teacher or science or math teacher. And they may do a wonderful job, but that is a concern."

Less than 20 percent of teachers feel competent to teach personal finance, according to the Council for Economic Education.

"When I was in high school, my math teacher had a Ph.D. in math, my English teacher had a Ph.D. in English and obviously they taught math and English," Morrison said. "Who teaches financial literacy? Well, if there isn't an integrative curriculum or required class, it may not get taught or it may get taught poorly."

But, she added, any learning experience is better than no learning experience.

"I can't teach them everything they need to know about the financial universe," she said, "but if I can teach them to be informed decision makers, then I'm making a difference."

Most students at Lookout Valley's Reality Check seemed to agree that the exercise was a good learning experience.

"I was down to $311 so I got a second job and went back to school," Desiree Woods, a ninth-grader, said. "It frustrated me, because I wanted to have more than that much left. I guess it's just a kick of the real world."