ONLINESee Marathon Oil Corp's video here: www.youtube.com/watch?v=VY34PQUiwOQTO LEARN MORE* What: Sierra Club meeting* When: 7:15 p.m. today* Where: Outdoor Chattanooga, 200 River St., Chattanooga, in Coolidge Park* Cost: Free

East Tennessee in coming years may find itself front and center in the growing debate over fracking - the hydraulic or nitrogen gas fracturing of shale rock deep underground to free natural gas.

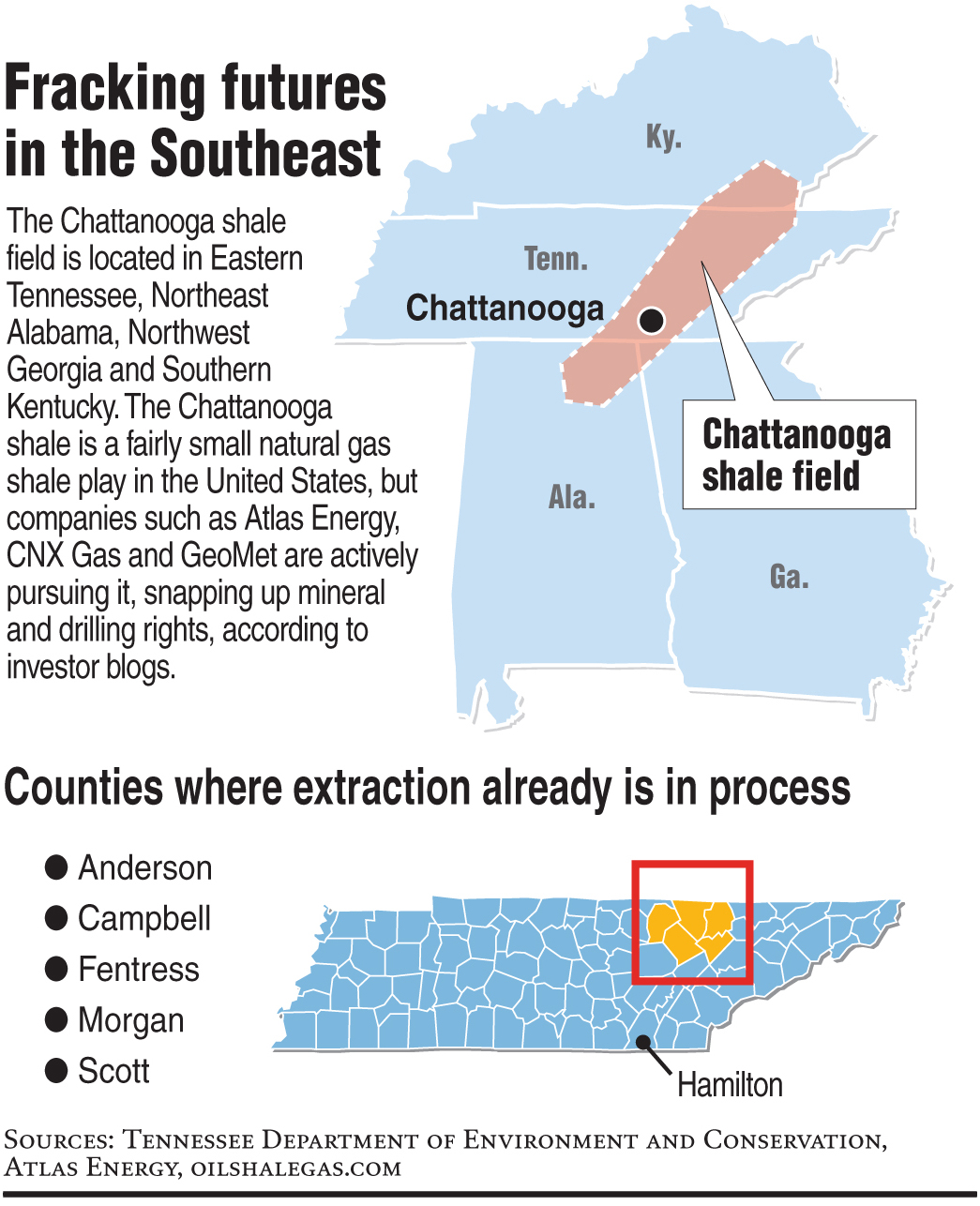

The region -- with Chattanooga at nearly dead center -- sits atop a layer, or "play" in driller language, of shale known as Chattanooga Shale.

No fewer than six natural gas drilling companies in recent years have looked at mineral rights and property leases in the Chattanooga Shale play to hunt for their next stake. Members of environmental groups speculate that a drilling lease already has been made in eastern or northern Hamilton County, based on industry blogs.

But the debate is not simple. Water wells and supplies in some states have become polluted with methane and drilling pollutants, so safe answers are complicated.

Everyone wants clean, safe water, and most everyone seems interested in America's energy independence.

The question is, can Tennessee find consensus in both? Perhaps not yet.

Henry Spratt, a biology professor for the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, will tell Chattanooga's Sierra Club today about his concerns that new state rules for gas drilling and fracking don't do nearly enough to protect water supplies.

"Sure, there's potential good for getting the gas out of the ground. But if you have one well that's messed up, then that whole area is messed up for a long time," Spratt said, pointing to states such as Pennsylvania, where some wells and water supplies are so polluted that they can catch fire.

Gas drilling industry officials say fracking "hysteria" is unfounded.

"Between 1 million and 2 million wells have been fracked since 1947," said John Bonar, general manager of Atlas Energy Tennessee, one of several gas-drilling companies looking at Tennessee's shale play. "It's a rare event when there's a problem. ... We're trying to get gas out of the ground. We don't want to lose it [in a water body or the air.] It's not in our interest to see it leak off."

How it works

Not all deposits of oil and gas are in large seas within the earth. Geologists say substantial amounts are trapped in deep shale rock formations.

New technology to allow horizontal drilling -- and fracking -- is being used to free the gas and bring it up for consumers.

According to industry and investment Web pages, a layer of Chattanooga shale running down East Tennessee into Northwest Georgia and Northeast Alabama is tempting at least six drilling companies.

"Atlas Energy has accumulated 105,000 net acres located in eastern Tennessee. The company believes that its acreage contains up to 500 potential horizontal drilling locations in the Chattanooga Shale," according to oilshalegas.com.

Meg Lockhart, spokeswoman with the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation, said no permits are approved or pending for fracking wells in Hamilton County.

There are such wells in Anderson, Campbell, Fentress, Morgan and Scott counties, state records show.

According to a Marathon Oil Corp. video recommended by Bonar, shale reservoirs are typically one mile or more below the earth's surface.

That's well below most sources of drinking water aquifers, which are 300 to 1,000 feet deep. And steel pipes, cemented in place with concrete casings, prevent fracking fluid and gases from getting into the aquifers.

What makes shale gas drilling different from other gas drilling is the need to drill horizontally, according to the informational video.

Along the horizontal bore, short vertical fractures are blasted into the surrounding rock. Then water, sand and chemicals -- or nitrogen gas and additives -- are pumped in at high pressure. The sand keeps the fractures open so gas can flow to the well bore.

From 15 to 50 percent of the "frack fluid" is recovered, the video states, and it is either reused or "safely disposed of according to government regulations."

Bonar said Chattanooga shale is too fragile for the high-pressure water fracking treatment, so nitrogen gas replaces some of the water.

"Nitrogen is 78 percent of our air, and it's relatively inert," he said, noting that it is important for the United States to be "energy independent."

Regulatory concerns

Environmental advocates say fracking -- with either large amounts of water or nitrogen gas and less water -- is just not that neat.

"Injecting nitrogen and water into a gas well in karst [cave and sinkhole-riddled] geology is bad," says Renee Hoyos, executive director of the Tennessee Clean Water Network. "It's bad for groundwater, drinking water and surface water."

In Pennsylvania, communities tell horror stories of having so much methane in their wells and water supplies that they become flammable.

Tennessee's new rules don't even require drillers to test wells or notify neighbors unless they pump in more than 200,000 gallons of water, Hoyos said.

Regulators have acknowledged that fracking most wells in Tennessee takes only about 175,000 gallons of water, she said.

And there's the question of Chattanooga Shale itself, which forms dangerous radon when exposed on a roadside or in a basement.

In New York, environmental advocates say waste fracking fluid contained levels of radioactive radium and other elements 100 to 1,000 times higher than federal drinking water standards.

Anne Davis and Gwen Parker, attorneys with the Southern Environmental Law Center, are fighting Tennessee's new gas and drilling rules -- which came about just as the state was streamlining regulatory agencies in the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation and merging the oil and gas board with the water quality board.

"On Sept. 20, the oil and gas board approved rules and then ceased existence and was merged with the water board as of Oct. 1, so it's now the water and oil and gas board," Davis said.

"The [Southern Environmental Law Center] has challenged the rules and sent a letter in late November to the Tennessee attorney general. We hope the attorney general will send them back to what will now be the water, oil and gas board, and that some more protective rules will be adopted," she said.

The question is still under review in the attorney general's office.

Rules hot seat

In October, reporters obtained handwritten notes from the state worker who supervises Tennessee's regulation of oil and gas production. The notes showed that the worker derided opponents of the hydraulic fracturing method of gas drilling as "stupid."

Michael Burton, with TDEC, acknowledged making the notes. He said he was venting his frustration on paper and apologized, saying the notes weren't intended to be made public.

A TDEC statement said the department disapproved of Burton's remarks.

There have been other recent stumbles for the fracking industry.

A University of Texas study that says hydraulic natural gas fracturing is safe has been withdrawn after an independent review by national experts found the study scientifically unsound and tainted by conflicts of interest.

The author, Dr. Charles Groat, and Dr. Raymond Orbach, head of the university's Energy Institute that released the study, have resigned.

The original fracking study concluded that hydraulic fracturing was safe, the danger of water contamination low and suggestions to the contrary mostly media bias.

But Groat sat on the board of a natural gas drilling company and received more than $1.5 million in compensation. That information was not disclosed in his report.

It was the third time in three months that fracking research by energy-friendly university industry consortiums has been discredited, according to a news report by National Public Radio.

The Shale Resources Institute at the State University of New York at Buffalo was closed after questions were raised about the quality and independence of its work. And an industry group canceled a fracking study after professors at Penn State University refused to participate.

Spratt worries about similar problems with Tennessee's new rules.

With Tennessee Gov. Bill Haslam's connections to the retail oil and petroleum business, Spratt wonders why state officials didn't at least embrace best-practices guidelines from the American Petroleum Institute.

"You would think [Haslam] would encourage that," Spratt said.

"The professional body that represents that field is generally where you go for the most reasonable perspective," he said. "To see [state officials] turn a blind eye to that -- I think that's telling, and I'm not glad to see that at all."