2,4,5-TP* Alternate name: Silvex* Common brand names: Fenoprop* Common use: Chlorinated herbicide, control of woody plants and rangeland improvement programs.* History: Banned in U.S. since 1985.* Regulation for Silvex went into effect in 1992. EPA required water suppliers to test for the product between 1993 and 1995.* Maximum contaminant level goal (MCLG): 0.5 parts per billion in water.* The EPA believes this figure to be "the lowest level to which water systems can reasonably be required to remove this contaminant should it occur in drinking water."All public water supplies (nationwide) must abide by these regulations.* Silvex bonds strongly to soil and "isn't likely" to leach to ground water. If released to water, Silvex bonds to sediment and is slowly degraded by microbes over time.* Short-term health effects: depression, nervous system effects, weakness, stomach irritation, minor kidney and liver damage.* Long-term health effects: kidney and liver damage.Source: Environmental Protection Agency

There's something in the water in Lookout Valley.

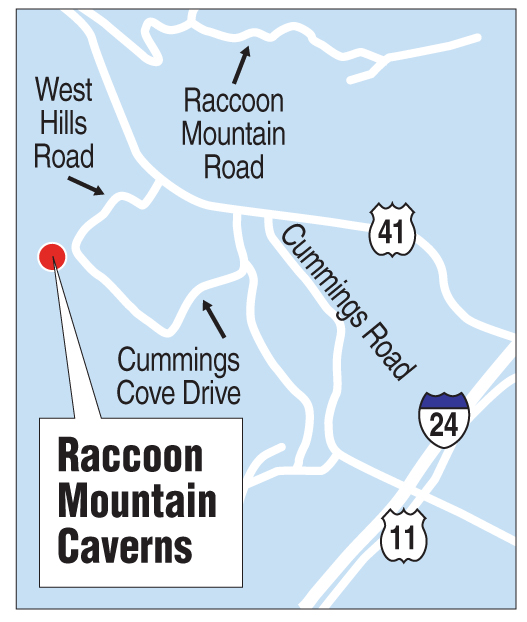

Jeff and Steven Perlaky, owners of Raccoon Mountain campgrounds, have been locked in a battle with Lookout Valley land developers for years over legal concerns about construction rights to Aetna Mountain Road.

And now, Jeff Perlaky says "nasty" things are finding their way into the nearby Raccoon Mountain Caverns at the bottom of the hill.

"We're starting to see chemicals in our cave water," Jeff Perlaky said.

Analytical Industrial Research Laboratories Inc., a water sampling company hired by the Perlakys, reported the harmful chlorinated herbicide Silvex was found in the brothers' cavern water on June 1.

Silvex, also known as "fenoprop" or 2,4,5-TP, has been banned in the U.S. by the EPA since 1985.

Only 3.6 parts per billion are allowed in tap water, and 470 parts per billion were found in the June 1 sample. Jeff Perlaky said the water did not include these chemicals in a test through the same company one year ago.

"If that was in tap water, you couldn't drink it," said Roy Patterson, technical director for the lab company.

Side effects include liver and kidney damage in humans.

"These things [chlorinated herbicides] were widely used," Patterson said. "They would get on plants, and then bugs would eat the plants, and birds would eat the bugs. But once it got there, it never left. I don't think it ever gets out of your system, and the only way to get it out is to wash it out."

According to an EPA fact sheet, the major source of Silvex in drinking water is residue of the banned herbicide sprayed around power lines to control vegetation growth.

Jeff Perlaky said that power lines, which occupy roughly 80 of the 1,200 acres donated to conservation efforts at the nearby Black Creek Mountain development, are sprayed with herbicides to kill vegetation. He said Silvex may have been used under these power lines.

He attributes the Silvex in his water to the bulldozing and construction at Black Creek.

But Doug Stein, the chairman of the Chattanooga City Stormwater Regulation Board and the developer of Black Creek, begs to differ.

Stein said his development's power lines and any chemical sprays under them are easements managed entirely by the Tennessee Valley Authority.

"Those power lines run across his [Jeff Perlaky's] property, too," Stein said. "There's no vegetation on them. They go across everybody's property up on that mountain. We don't have anything to do with it."

Some locals at the mountain expressed concern about water flow from Stein's property. Photos supplied to the Times Free Press indicated large runoffs of muddy water from Stein's property and damaged silt fences meant to control water runoff.

"We have used them extensively," Stein said. "Not just silt fences, but we have had a SWPPP [storm water pollution prevention plan] that was drawn by an engineer that we have adhered to."

According to the National Weather Service, the Lookout Valley region has received up to 10 inches of rain within the last 10 days, and saw an especially soggy Independence Day weekend.

"If you had gone to any construction site in the Southeast, especially that week when we had 10.3 or 10.4 inches or rain, you would not see any differently," Stein said. "We've been in contact with TDEC and the city about ours. We went out there and fixed the rain [fences] as soon as the rain stopped. We've had some vandals destroy part of [the silt fences], but we've fixed them every time."

Stein says vandals have disrupted his silt fences for years, and the most recent incident occurred just days ago.

According to an EPA fact sheet, Silvex bonds to ground sediments but "isn't likely to travel" only through ground water. If released to water, microbes slowly degrade Silvex residues over time.

The Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation, or TDEC, said it does not know when TVA last used Silvex to spray under power lines, if ever. TVA was not able to immediately confirm whether the chlorinated herbicide was used.

However the Silvex got into Jeff Perlaky's water, the new challenge of removing the herbicide from the land will be a tricky one.

"If you put it in the ground, it's there forever and it gets a little diluted by rain," Patterson said. "After 20, 30, 40, 50 years, maybe it goes away, but maybe it doesn't."

The dispute between the Stein and the Perlaky brothers is the latest fracas surrounding Aetna Mountain Road and Lookout Valley, which backers call "the last undeveloped mountain area in Chattanooga."

The Black Creek Mountain development group secured a $9 million TIF, or tax increment financing, to fund a road allowing it to build a $500 million mountaintop development that could parallel communities like Lookout Mountain and Signal Mountain.

The issue of conservation in the area is a tricky one. In 2011, four-wheelers and off-road vehicles were banned from Aetna Mountain Road after concerns of "degradation of the property" leading to the runoff of muddy, silty stormwater, as well as landslides causing issues of personal safety.

Jeff Perlaky said the Silvex residue was found in the back of the caverns, so he does not necessarily worry about human contact with the herbicide during its daily operations of sightseeing exploration. However, he is concerned about the cave's natural ecosystem, and has contacted environmental groups in response.

The Raccoon Mountain Caverns, originally billed as "The Crystal Cave" during commercial tours in the 1960s, serves as home to several endangered species including the Indiana gray bat.

The "nesticus furtivus," or the blind cave spider, is known only to exist in the Raccoon Mountain Caverns that draw upon the water containing Silvex.

While Silvex is known to cause liver and kidney damage in humans, Jeff Perlaky said he does not know what it could do to the species in his cave.

"I don't picture it being good for them," Jeff Perlaky said. "I certainly worry what adverse affects it would have on them. Some of the ecosystems are so fragile. Any little something can lead to the demise of something else."

Contact staff writer Jeff LaFave at jlafave@timesfree press or 423-757-6592.