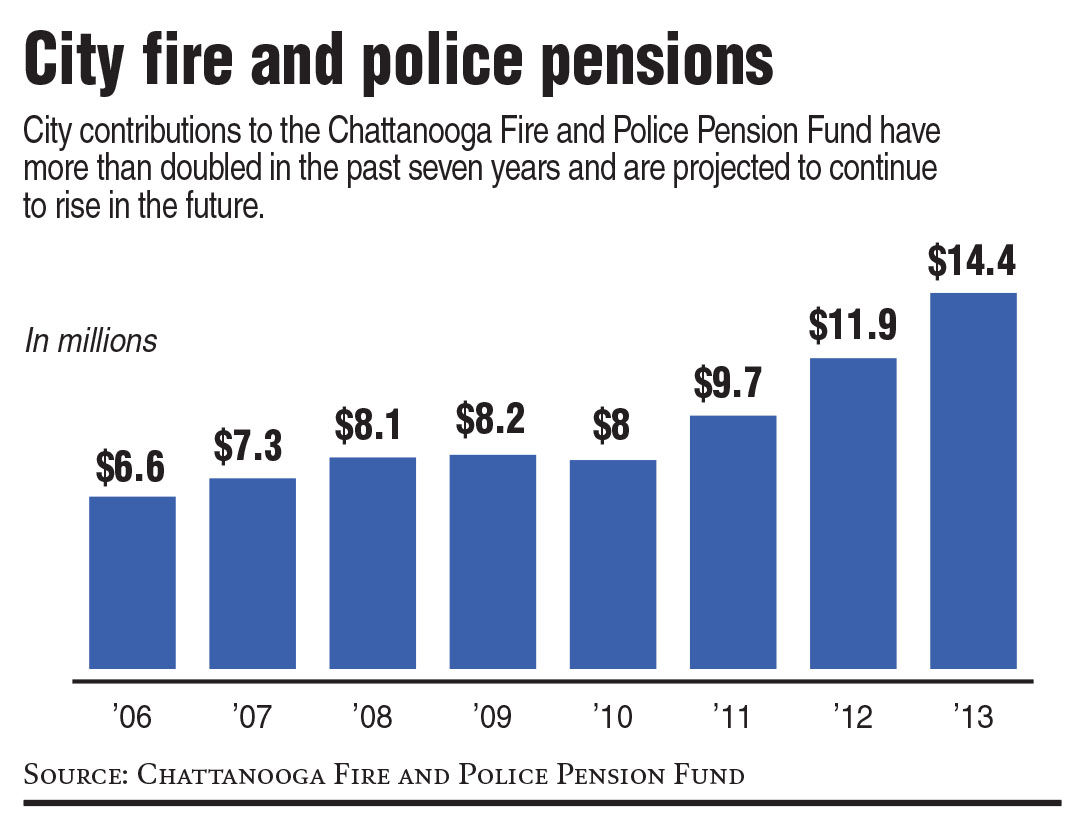

FUND AT A GLANCEEstablished: 1949Participants: 733 retirees and dependents and 818 active police officers and firefighters.* Assets: $212 million* Unfunded liabilities: $149.7 million* City taxpayer contribution: $14.4 million, up $2.1 million from last year* Employee contribution: 8-9 percent of pay, totaling about $3.5 million a yearSource: Chattanooga Fire and Police Pension FundPOSSIBLE CHANGESPFM and the pension plan task force will look at changes:• Reducing the guaranteed 3 percent cost-of-living increase• Setting a minimum retirement age• Raising the contribution rate for workers and the city• Cutting disability and retirement benefits• Requiring new employees to work longer to get full retirement benefits• Issuing pension obligation bondsSource: Chattanooga

After losing millions of dollars in the police and firefighters retirement fund from the 2008 stock market collapse, former Mayor Ron Littlefield created a task force to address how to put the pension plan on more secure footing.

The group studied and debated the problem for six months, but ultimately agreed only to add a couple of outside members to the Chattanooga Police and Fire Pension Board, revamp the terms of a deferred retirement option for some members and smooth out the city's payments into the underfunded plan over an entire decade.

The study group left it to the next administration to figure out how to fund the plan fully.

"It's a very tough problem," said Dan Johnson, a CPA who as Littlefield's chief of staff was tasked with seeking a way to shore up the plan. "It's something that has to be dealt with, but I'm afraid until there is a crisis it's going to be difficult to do very much."

Now Mayor Andy Berke is appointing a new committee to tackle an even bigger shortfall in the pension program that covers more than 1,500 active and retired police officers and firefighters. Last week he hired consulting firm Public Financial Management Inc. to work with the task force and the pension board.

"You can see from the issues that have been going on throughout our country with regard to pension costs, this is something you want to address before the crisis escalates beyond repair," Berke said.

Cities across the country are staring at looming shortfalls in their pension programs, said Steve Stanek, an expert for the Heartland Institute, a conservative and libertarian think tank. This month's bankruptcy of Detroit -- the largest municipal bankruptcy in history -- and Chicago's recent credit downgrade, to a large extent, were both because of unfunded pension liabilities.

The drop in investment returns, longer lifespans for retirees and generous benefits promised during better times have combined to undermine the financial health of many public pension plans.

Fire and police pensions such as the one in Chattanooga are especially vulnerable because participants aren't included in Social Security and retirement benefits are paid to many workers still in their 40s.

•••

By one actuarial estimate, Chattanooga's fire and police pension has only about 63 percent of what is recommended to meet all of its future benefits.

But another report suggests that if an additional $47 million of unrecognized losses are included, the plan is only 52 percent funded. By that measure, the fire and police pension needs $197 million more to meet future obligations if no changes are made in the plan.

PFM and the task force will look at changes, but city pension board members say the future isn't as bleak as the administration is painting it and the board already has studied solutions.

"We don't believe it's a crisis," said Police and Fire Pension Board Chairman Terry Knowles.

The Berke administration still is assembling the task force, and officials insist they have no predetermined idea about the best way to address the shortfall.

Pension board members say they have been offered one seat on the task force, but Knowles has asked for two so the police and fire departments both will be represented.

Travis McDonough, the mayor's chief of staff, has met with members of the Chattanooga Fire and Police Pension Board a handful of times and said he is confident the task force can reach consensus by the end of the year.

"I'm confident we will do some good work and get to a solution that makes sure we continue to retain good people for long careers, keep the program financially solvent and be responsible to the city's taxpayers," McDonough said.

Some pension board members remain wary, and retirees are worried.

"Everybody's concerned," said Mike Williams, retired deputy police chief. "You work for 28 years for an amount of money and for a pension promised to you. Now that we are retired, it would be egregious to change it."

Sgt. Tim Tomisek, president of the International Brotherhood of Police Officers, said officers are worried because of the all the uncertainty surrounding the task force.

•••

Chattanooga's present plan allows firefighters and police officers to retire at any age after 25 years of service and be paid more than two-thirds of their average earnings in the last three years of employment.

By comparison, Knoxville's sworn personnel must be at least 50 years old to qualify for full benefits, while the minimum age is 53 in Nashville and 55 in Atlanta.

For the past 15 years, Chattanooga firefighters and police officers also have been encouraged not to work longer than 28 or 30 years through a deferred retirement option plan. The so-called DROP was added under former Mayor Jon Kinsey to encourage turnover and a more youthful, physically fit staff.

"We had one 72-year-old firefighter at that time that we had to put a milk carton down to help him step out of the firetruck," said Frank Hamilton, the fund administrator for the pension board. "These are tough and important jobs that you can't have seniors performing."

To encourage high-ranking officers to retire back then, Kinsey also pushed through a plan to remove the salary cap upon which retirement benefits were previously calculated.

Those changes, plus Littlefield's request to stretch out the city's payments to replenish the fund after the stock market collapse in 2008 -- combined to drive up costs while limiting what the city paid into the plan.

•••

Before Berke took office in April, Knowles said he and other board members briefed the soon-to-be administration on what the pension board was facing and the board's willingness to work together.

But the Monday before Berke's announcement, McDonough went to a police and fire pension board meeting and said the city would start its own task force to study controlling costs for the fund.

The pension board had given the city an actuarial study by The Segal Group recommending the city fully fund the plan over the next 25 or 30 years. That would drive up the city's annual costs from $14.4 million this year up to nearly $40 million by 2038.

But pension officials say making one or more simple changes could mean the city would save $12 million and its contribution wouldn't exceed $28 million, according to Frank Hamilton, the fund administrator for the pension board.

"I was so disappointed," he said. "The task force at this point is unnecessary. But the mayor has made a decision, and we look forward to being a part of these discussions."

•••

PFM officials said they have overcome similar problems in other cities, including Lexington, Ky., to find a consensus about ways to replenish underfunded pensions.

Vijay Kapoor, a PFM director who worked in Lexington and will work with the Chattanooga task force, said there were similar anxieties about ongoing shortfalls in the Lexington fire and police pension after two task forces had failed to resolve the problem.

He said PFM officials managed to bring city, police and firefighters and state legislators together to find a solution within three months.

"We didn't have any preconceived notions about what the end result would look like," he said. "But we were able to offer not only technical advice, we also were able to sit down and realistically talk with everyone about the options and the need for a solution.

"It's helpful, I think, to have an outside, third party offer you ideas and analysis to show what the impact of various changes would be and work to ultimately bring about a consensus for change."

The plan adopted by the city and approved by the Kentucky Legislature cut cost-of-living increases, raised contributions for workers and the city, required new employees to work longer to get benefits and limited some disability and retirement benefits until the fund is replenished. The changes cut Lexington's unfunded liability by 45 percent.

"This was not easy, but in the end we have a plan that finally puts our pension fund on sound footing," said Lexington Fire Capt. Chris Bartley, president of the International Association of Firefighters Local 526.

Despite Lexington's success, some pension board members and union leaders in Chattanooga are concerned that their voices adequately are represented on the task force.

"We're willing to sit down and look at everything," Knowles said.

The City Council and the Chattanooga Fire and Police Pension Board must agree to any change in pension benefits under the current City Charter. Otherwise, voters would have to approve the pension changes in a citywide election.

"We want to find a way to resolve this issue and reach consensus without going that route," McDonough said.

Contact staff writers Joy Lukachick at jlukachick@timesfreepress.com or Dave Flessner at dflessner@times freepress.com.