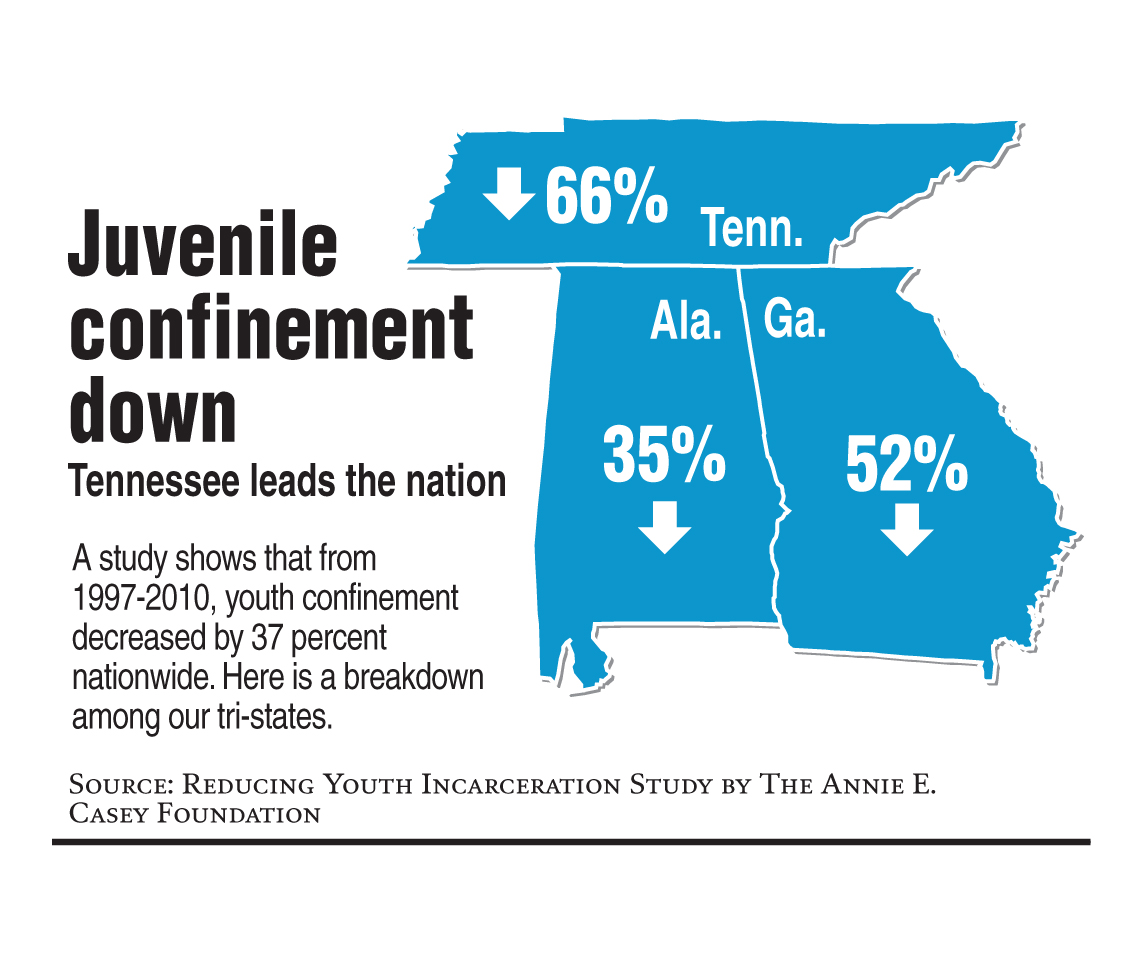

A new study showing that fewer states are locking up juveniles also reports that Tennessee's rate of youth incarceration has dropped 66 percent, the most of any state.

The Annie E. Casey Foundation study looked at youth incarceration rates from 1997 to 2010.

Tennessee had the greatest reduction. Georgia's rate of reduction ranked fourth, with 52 percent. Alabama's rate, 35 percent, tied with two other states for 17th but fell short of the national average of 37 percent. Six states had youth incarceration increases while seven had declines of more than 50 percent.

Over the past four years Bradley County has halved the number of youths it sends to state centers or places on probation, said Terry Gallaher, director of the county's Juvenile Court program.

In both Georgia and Tennessee, officials credited improved, evidence-based assessments with improving juvenile justice in recent years.

Linda O'Neal, executive director of the Tennessee Commission on Children and Youth for 24 years, applauded the reduced numbers and said there are chances to keep improving.

O'Neal said research shows confining juveniles, especially for nonviolent offenses, causes lifelong consequences. Those may include lower levels of education, increased unemployment, drug and alcohol abuse and more criminal problems as adults.

Community-based programs that help keep young offenders in school and near families are "a more cost-effective and humane way to turn their lives around," O'Neal said.

The commission receives some funding from the Annie E. Casey Foundation.

In Georgia, Walker County Juvenile Court Judge Bryant Henry said similar strategies in the Peach State have had an impact.

A Juvenile Court judge since 1997, Henry works with the state's Council of Juvenile Court Judges. He said the graduated sanction program available to probation officers helps keep minor offenders out of court and gives them a better chance at rehabilitation.

"That's helped reduce the number of people in detention," he said. "It's a probation management tool they can [use to] deal with [offenders] in-house."

The program, put in place in the past eight years, allows probation officers to deal with minor probation violations by providing services. Before, Henry said, many of the minor offenses would bring youths back to court and then to detention centers.

Tennessee officials faced the same problem. Albert Dawson has worked with the Tennessee Department of Children's Services for 40 years. He is the department's deputy commissioner of juvenile justice.

"At one point in time the only option we had was the youth development center [juvenile lockup]," Dawson said. Later the department began using group homes and other placement methods, depending on a juvenile's status.

But in 2007 the department put a detailed assessment in action. The assessor evaluates the total of a child's life -- criminal history, substance abuse, parental support, school problems.

Once the offender is assigned a score, the department can more easily decide how what to do.

"Prior to this [assessment] the placements were quite subjective," Dawson said.

But the best tools for keeping kids out of court in the first place happens much earlier, Dawson and O'Neal said.

"Some of the solutions are really long term," O'Neal said. "Early childhood education programs, home visits, parents as teachers programs."

In Bradley County, Gallaher said Juvenile Court workers had a major philosophy shift five years ago. Case worker funding from the state was cut and people working with youth had to come together and figure out a way to improve.

Since that time they've partnered with local schools, a private social work company, law enforcement, addiction treatment centers and Lee University to put strategies in place that work with all aspects of youth problems.

"What we've done is a lot of preventative intervention that deals with issues at the root of the problem, usually rooted in family breakdown," Gallaher said.

A 15-year veteran of Juvenile Court, Gallaher admitted there were times he'd be near to burning out when watching youths continually re-offend. But the newer methods are helping a lot and are worth the effort, he said.

"It's a lot more work," he said. "It's like trying to restore a vehicle rather than junking it and getting a new one."