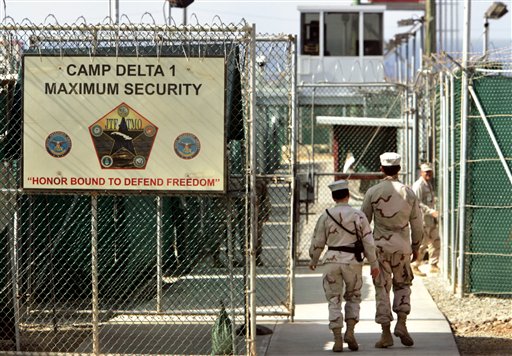

It's been conveniently easy in recent years for Americans not to think about the Pentagon's penal facility at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, where 166 men remain imprisoned. Though more than two-thirds of these men have never been charged with anything, and though many have been detained for more than a decade without any movement to prosecute them, they are too isolated and too far away to prompt much concern here in the United States about their unconstitutional imprisonment. Never mind that Washington has essentially locked them up and thrown away the keys.

The continuing three-month hunger strike by more than 100 of these prisoners -- and the unethical tubal force-feeding imposed by the Obama administration on 22 of them -- is now making it impossible for Washington, and the country at large, to keep blinders on. President Obama, whose 2009 pledge to close the Guantanamo prison was thwarted by Congress, acknowledged Tuesday that this legal limbo is harming the country and can't be allowed to continue.

"The idea that we would still maintain forever a group of individuals who have not been tried," he said, "is contrary to who we are, contrary to our interests, and it needs to stop." He is correct. This nation's permanent unwarranted detention of people without charges and judicial disposition is a huge stain on the legal values we proclaim. It further fosters hatred of the United States among extremists, who exploit our legal hypocrisy and continue to fuel al-Qaida-style terrorism.

But while a refocused Obama could still do much too alleviate the detention issues at Guantanamo that have festered in the aftermath of the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, he cannot fix this problem on his own.

Congress wrongly decreed several years ago that federal money could not be used to repatriate or transfer Guantanamo's detainees to other countries. It also made transfers subject to difficult waivers that were required of the Pentagon. These obstacles have barred transfers for the 50 percent of Guantanamo detainees who are not accused or reasonably suspected of any wrongdoing, and who have already been cleared for release.

Congress has also blocked the administration's proposal to provide trials in the United States and imprisonment in super-maximum penitentiaries for the other half of detainees. Yet the Pentagon's military tribunals have also proved inadequate to the legal challenges. Presently, just six of the 166 detainees face charges before tribunals. Another group of nearly 50 detainees are classified as too dangerous to be released, but unfit for trial because of insufficient evidence, or because the evidence, at least in part, is connected to torture in their interrogations.

Amid the futility of the Pentagon's military tribunals and the restrictions on waivers and transfers, Obama dropped the ball. He effectively quit trying to overcome the congressional barriers. With the hunger-strike coming on top of a recent proposal by the Pentagon to invest $200 million in revamping the Guantanamo facility, Obama has plenty of reason to re-energize his initial pledge to close down the Guantanamo complex.

He should use this moment to reappoint an administration official charged with working through the barriers to make waivers and transfers possible. A White House official should also have the clout to lobby Congress for a workable judicial method to deal with the other detainees, and to close down the Cuban remnant of the former Bush administration's off-shored detainees.

In the interim, Obama has to square his stated desire to see that the hunger-strikers do not die with their own undeniable medical right to refuse food in protest of the conditions of interminable, unwarranted detention. If the president would begin immediately to deal with the issue of unreasonable detention, the hunger strikers might find reason to eat, and to live.