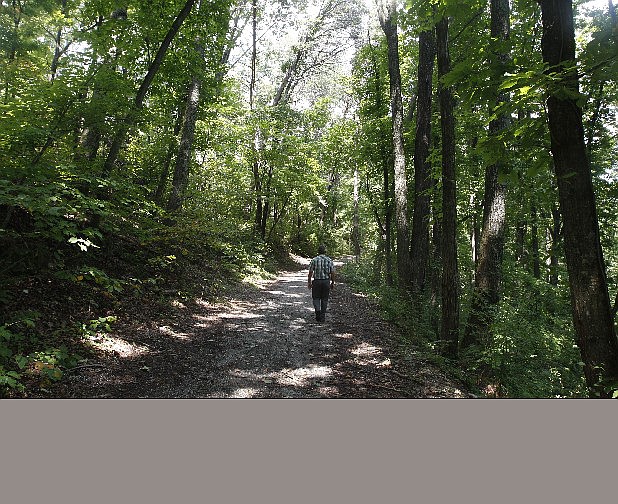

An urban park vision that grew out of a zoning controversy has become a 103-acre reality with about 8 miles of mountain biking and hiking/running trails that connect North Chattanooga to Red Bank and eventually perhaps to Moccasin Bend.

Stringer's Ridge Park will formally open Saturday, and when it does it will be an urban forest surrounded by about 28,000 residents and 47,000 Chattanooga and Red Bank workers.

It has taken plenty of patience, determination and cooperation - more than five years of effort and about $2.6 million in donations and volunteer hours - to get to this day.

When the work began in 2008, it was the consequence of a mutiny by residents of North Chattanooga's Hill City where homes sat at the base of the ridge. The residents feared for their property values, their quality of life, their health and their forested ridge view if the site's developer succeeded in gaining city approval to take off the top of the historic ridge in order to build 500 condominiums and townhouses.

The plan brought a storm of attention. Questions were raised about exposing Chattanooga shale, a rock that produces radon gas and sulfuric acid runoff when open to air and rain. Similar ridge-top development along another section of the ridge had caused runoff problems, and those concerns, along with the beginning of the recession, prompted developers to announce in April 2008 that they were backing away from the plan.

But debating the condo plan, against the historic and pastoral backdrop that Stringer's Ridge holds in Chattanooga, galvanized many in the city: What, after all, would be the effect on the Scenic City if a green ridge that frames the river-and-sky-view from downtown was suddenly all condos? Some in the city even suggested new legislation to help protect the city's iconic views from threats of brow and ridge residential development and cell towers. The marching cry was "remember Cameron Hill," another historic site and a once miniature version of Lookout Mountain that was flattened for condos decades ago then shortened again in recent years for the BlueCross BlueShield building.

In the months that followed, the owner, Jimmy Hudson, agreed to sell some of the property to the Trust for Public Land, and later he agreed to donate still more.

Hudson acknowledged at the time that he hadn't at first understood the public fervor over changing Chattanooga's view.

"I didn't envision it going this way," he said. "But I think that process helped us realize what it really was worth. I guess you could say we all took it for granted."

The view works both ways. Not only is it gorgeous from the city, looking north. It's also gorgeous from the trail-crossed ridge where part of the new park is a knockout overlook pavilion funded chiefly by the Lyndhurst Foundation.

"It's a $2 million view," quips Rick Wood, Tennessee director of the Trust for Public Land. Volunteers built the trails that were designed sustainably by a premier trail building company, also paid for by Lyndhurst.

The whole effort makes Chattanooga - today and tomorrow and in decades to come - a city that will still have it's iconic scenery, along with a calming, peaceful, 103-acre urban forest and park, all pretty much smack in the middle of everything. And the only city taxpayer investment is $500,000, which the city paid over two budget years.

How lucky we are.