Plagiarism: The numbers on stolen words• 21 percent of students say they've downloaded a paper or report to turn in• 38 percent of students have directly copied text for use in an assignment• 55 percent of college presidents say plagiarism has increased• 89 percent of college presidents say the Internet and technology plays a major role in plagiarismSource: TurnItIn.com, Pew Research Data

As the Internet has made researching a point-and-click breeze - and plagiarizing even easier - the stakes have never been higher for instructors to maintain classroom integrity.

According to a Pew Research Center survey, 89 percent of college professors say the Internet and new technology in the classroom are making plagiarism easier and more common.

Students are being introduced to classroom technology at ever-earlier ages. And 68 percent of Pew's 2,400 surveyed middle- and high-school teachers say the advances also threaten to make students more likely to "take shortcuts and put no effort into their writing."

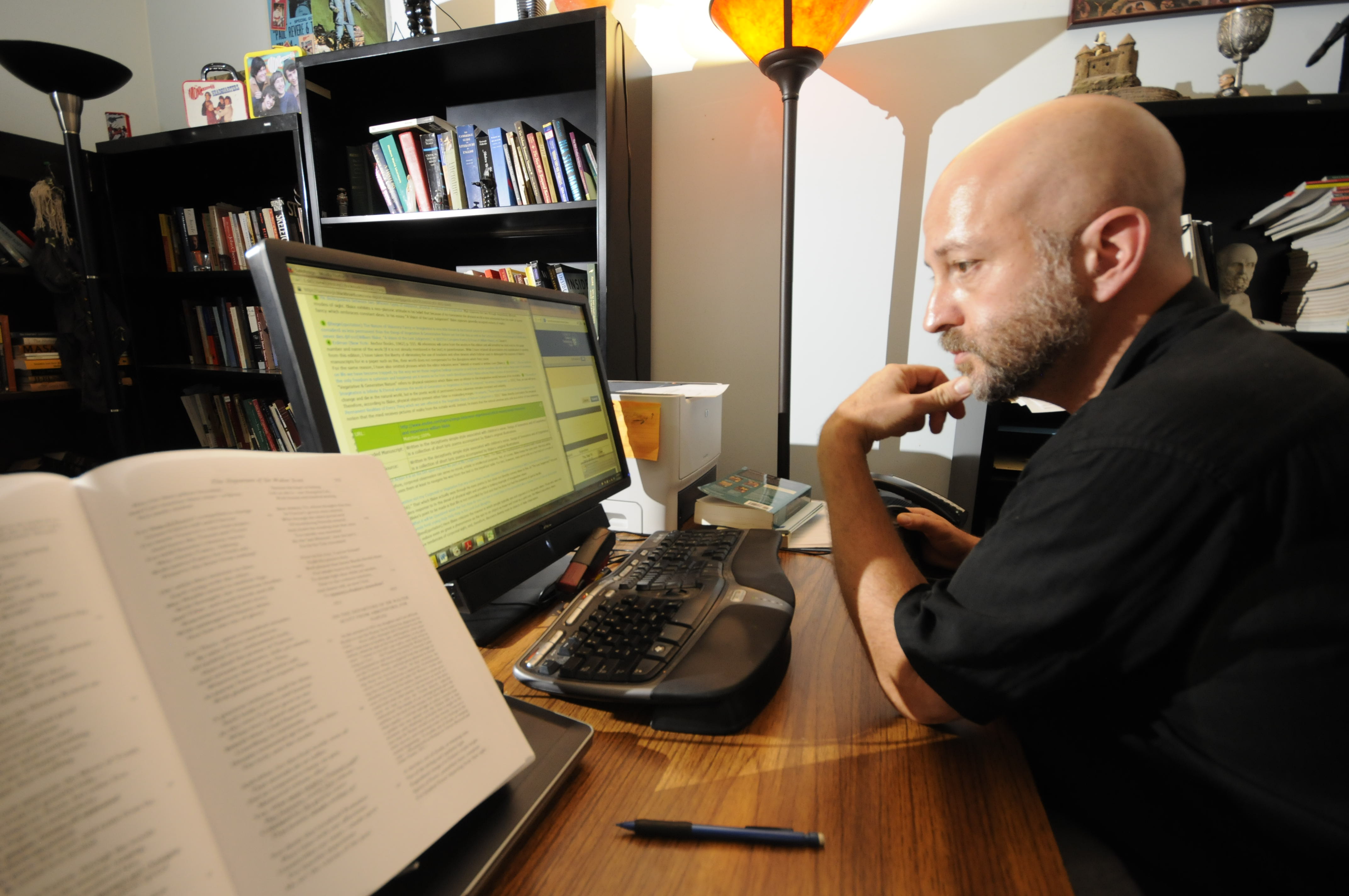

University of Tennessee at Chattanooga professor Tom Balázs is among the countless instructors taking a zero-tolerance stand. He continues to find ethics violations in his classes. One plagiarizing student got the boot during the second week of class.

"In the old days, students used to go to the Encyclopedia Britannica, but now they go to the Internet," Balázs said. "The only difference is that now, they don't have to type what they find."

Balázs instructs a variety of English courses. He loves the classics: Homer. Dante. Shakespeare. After 20 years in the classroom, he has developed an extremely low tolerance for feigned work.

Now that his students have limitless access to Wikipedia, Spark-Notes and paid-paper services, he's concerned for their future.

"It's a double-edged sword," he said. "It makes it easier to plagiarize, but it makes it just as easy to get caught."

Classroom consequences can follow students into their career aspirations. Steven Cox, chairman of the UTC Honor Court, met with 14 students regarding plagiarism or cheating in 2012-13, his first year. All but two students failed their respective courses and were placed on academic probation.

"It shows up on their transcripts," Cox said. "And it's never a good thing to have an F on your transcript, especially for plagiarism."

It's not difficult for Balázs to detect it, either. He has read so many papers and quick-help sources that he can catch many instances of plagiarism right away. He embraces SafeAssign, a Web program that juxtaposes student papers against professional sources to detect cheating.

"Students panic," he said. "Something is due the next day, and they feel like they don't have time to do the work. Instead of seeking extra help, they try to take a shortcut."

If Balázs questions a paper's authenticity, he meets with the student. If he can determine that someone else's work has been passed off as the student's own, he or she fails his course.

The burning image of plagiarism is the student who copied-and-pasted his way to a diploma, but a heavy-hitter in the plagiarism detection business said there's a growing culture of students who have little idea how to cite properly. When these students fail to acknowledge a source, they inadvertently plagiarize.

"We see this a lot in entry-level courses," said Jason Chu, education director for TurnItIn.com, another online plagiarism detection service. "Students don't have the background knowledge, the discourse or the vocabulary to write intelligently about a subject they know nothing about."

In Balázs' classes, he says he can tell when students are cheating simply by their use of language above their comprehension level. He recalls when a "C-level" student in his Western humanities class wrote a paper on Jane Eyre using sophisticated vocabulary.

A Google search later, Balázs found the exact paper on another Web page, copied word for word. Chu said this aspect of plagiarism is best resolved by knowing students and their personal work habits, but the idea becomes implausible as class sizes grow to all-time highs.

"Do you really have the time to create unique assignments for every single class and every single semester as you're trying to engage 400 students at once?" he said.

Common steps to avoid plagiarism include in-class writing assignments and breaking essays into multiple drafts, but new school methodology is trying to break this mold.

Chu's advice for educators is to create "plagiarism-proof" assignments. These outside-the-box tasks keep the same level of knowledge, but shift the writing perspective in a way that few resources likely exist to be copied.

Instead of a report on icebergs, which an encyclopedia could mimic, Chu would ask students to write an autobiography from the iceberg's perspective. The "I" and "me" references change the game.

Balázs, however, says that doesn't work.

"It requires you, as a teacher, to do all sorts of gymnastics and avoid all sorts of reasonable questions you would want your students to address," he said. "That hamstrings me as a professor."

Gail Chuy, East Hamilton High School principal, said her school recognizes instances of plagiarism but works to embrace corrective habits. Many of her teachers will give plagiarizing students a second chance to write the paper.

Their credit may be reduced and reputation checked, but she says it's better for her students in the long run to get a mulligan.

"You don't have to have severe punishment with kids for them to get the point," she said.

Chuy and her administration have yet to use a service such as TurnItIn or SafeAssign and would only do so if the problem got out of hand. Their main approach, she says, is to let teachers maintain a subjective and personalized classroom format in lieu of hard-and-fast rules.

"The more power you give a teacher, the better it's going to be," she said. "It is, after all, a learning experience."

Contact staff writer Jeff LaFave at jlafave@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6592.