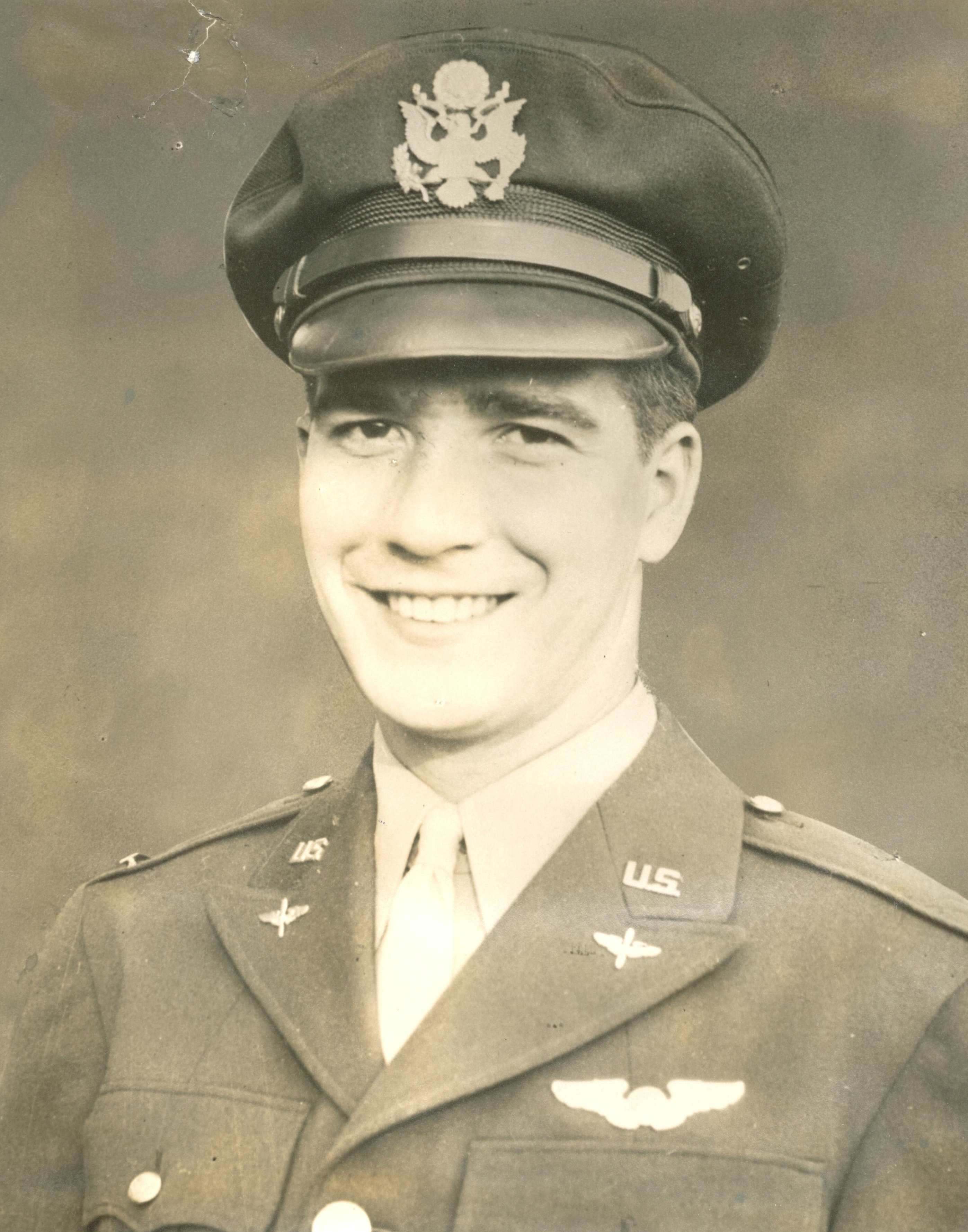

Francis "Bud" Peacock III displays a replica of the B-17 plane his father, Francis Peacock Jr., flew in during World War II, his father's prisoner of war papers, which include a photograph from when he was captured, and pieces of the actual plane with bullets recovered from the

crash site. Bud Peacock traveled to Germany to meet the pilot who shot his father's plane down over the North Sea during WWII.

Francis "Bud" Peacock III displays a replica of the B-17 plane his father, Francis Peacock Jr., flew in during World War II, his father's prisoner of war papers, which include a photograph from when he was captured, and pieces of the actual plane with bullets recovered from the

crash site. Bud Peacock traveled to Germany to meet the pilot who shot his father's plane down over the North Sea during WWII.For the German fighter pilot, a man who would fly 241 combat missions, the crippling of an American B-17 plane in World War II was just another day up in the office.

"I tried not to think about it," Hans Müller told Chattanoogan Francis "Bud" Peacock last year

Peacock's father, also named Francis, was onboard the B-17 when it was shot down on Feb. 22, 1944. But the German ace, now a spry 92-year-old living in Heidelberg, Germany, also said he was thrilled to see all 10 parachutes from the flight crew - including one with the senior Peacock dangling beneath it - open successfully and descend.

"I said, 'Thanks,'" a moved Peacock, 65, told Müller. The German reached over, patted him on the leg and said, "I'm a father. I know what you're thinking."

The two men - the pilot and the son of the navigator of the B-17 named Pot O'Gold - were put together in June by a history-loving Danish man who was captivated by the WWII incident that occurred near the Northwest Denmark town where he was raised.

Nikolaj Bojer, who was not alive when the parachutes came down and the plane crash landed in a field near Hoerdum, Denmark, nevertheless grew up hearing about the incident and the impact it made on the area. The region around Hoerdum, where Bojer lived, was not used to aerial combat during the war.

In 2008, he had connected the Pot O'Gold's ball turret gunner, Lester Shrenk of Bloomington, Minn., with Danish residents eager to meet him. Then, after learning the German pilot was alive and not in one of the cemeteries on which Bojer had centered his online search, he reached out to Müller in 2012.

Bojer contacted Peacock, whose father died in 1983, and offered to arrange a visit to the area where his father landed and also to meet Müller. Peacock, owner of Benchmark Trust Corp. and a former owner of the Mainly Soup, Mountain Pizza and Bungalow restaurants, quickly accepted.

NO MILK RUN

Peacock says his father's plane, flying out of England, was a part of a WWII mission to bomb an air base at Aalborg, but ultimately was a distraction to draw attention away from the bombing of a more important target. However, clouds obscured Aalborg, so the planes dropped their bombs in the North Sea and headed back to England.

"It was just supposed to be a milk run (easy mission)," he says.

Müller, who was scheduled to be in the air that day only as an observer, did not have the expected backup from other fighter pilots by the time he spied the B-17s. Flying a Junger Ju 88, he shot down one of the B-17s, nicknamed Hot Rock, then hit the Pot O'Gold, which immediately dropped its landing gear in an informal gesture of surrender and turned away from the North Sea toward land. Müller followed the plane about 150 miles and, after its crew's parachutes opened over land, shot its wing, which caused the plane to slam into a farmer's field.

The pilot, according to Peacock, could have finished off the plane over the North Sea, then actually disobeyed orders to do so once it reached the coast. But, he says, Müller "spared my father's life where many other men would not have."

"In a war where one fights for one's country on terms set from the administration," Bojer said when Shrenk and Müller met in 2012, "there was even a place for Hans Hermann Müller to control the situation. Hans Hermann, by your acts of doing your duty, you also proved that your heart was in the right place, set in the chest of a real gentleman. You were most noble in your conduct of acting."

Of the Pot O'Gold crew, the pilot, William Ralph Lavies, landed on the thin ice of Lake Ove and died of hypothermia. Eight others landed in various places but were captured and brought together within an hour, according to information compiled by Bojer.

Peacock, on only his 10th mission, landed more widely separated from the others, and was free for a day but eventually was captured.

As an officer, his father was fortunate in his prison housing, the younger Peacock says. He was housed by the Luftwaffe, the German military aerial branch during the war, rather than in a camp run by the German army.

"They treated him stern but not cruelly," says Peacock. "The officers had more camaraderie."

His father and other officers got to cook their food - vegetables, dark bread, horse meat, Red Cross offerings - in their room, he says. His mother, Catherine, however, did not know for six months that her husband was a prisoner of war and not missing in action, Peacock says.

The journal that his father was allowed to keep included, among other things, the books he read, the rations he was given and an architectural sketch of the quarters in which he was housed. On May 1, 1945, he was able to write: "Hitler dead! (10:20 p.m.). Russians arrive. Finally (10:25 p.m.). My God, it's over."

Their German captors, the younger Peacock says, fled in the middle of the night. His dad had been in captivity a little over 14 months.

NOTHING LIKE IT

When meeting Müller, Peacock and his wife traveled first to Heidelberg. The German ace was "nice, intelligent and polished" and spoke English, Peacock says. After the war, he remained in the German Air Force, worked with NATO and, prior to retirement, rose to the rank of colonel. He also turned down an opportunity to lead the German Air Force.

Peacock says his dad, a Pittsburgh native who received degrees in chemical engineering and civil engineering and became an officer in the Seabees, the Navy Construction Battalion, would have liked Müller.

"Dad always said Americans were ... like Germans," though they were enemies during the war, he says. "I think my father and this man would have felt comfortable with each other. They were a lot alike," both exhibiting humor, kindness and sharpness.

Peacock says Müller, when discussing his role as a pilot, viewed it as more "technical in his mind, just his job." He had to separate it, Müller told the Chattanoogan, from the rest of his life or he would have had "difficulty."

After spending time with the pilot, the Peacocks drove to Northwest Denmark, where the residents in 1944 had "never seen anything like" the parachutes floating and the plane rocketing toward the ground, Bojer says.

One woman, now in her 90s, remembered seeing the plane come in. One man, then a boy, retrieved the plane's door hatch and hid it in a barn. One group, in the middle of a funeral procession when the plane came down, dropped the casket in the road and fled, Bojer was told.

Danes are known for their stoicism and steadiness, but seeing a B-17 crash "was a big deal to them," Peacock says. "They couldn't wait to meet us."

While in the area, he and wife also saw the coastline where the plane first went over land, the lake where the pilot perished, the school where his father's captured crew was initially assembled and the spot in the field - then planted in barley - where the plane crashed.

The owners of the field, according to Peacock, hosted them for dinner and showed him one of the propellers from the plane. They also gave him several bullets from the B-17 and several small pieces from the engine and the radio.

"The farmer said they were always digging things up [from the B-17]," he says.

Peacock, whose North Chattanooga office is filled with photos, model planes and souvenirs of the WWII era, says the trip proved that the war continues to have an impact, not only on those who fought it but the noncombatants who lived through it and the generations that came after it.

On Feb. 22, 1944, the day his plane was shot down, Peacock's father was 22, Shrenk was 20, the pilot Lavies and Müller were 23. Some of the witnesses Peacock spoke to in Denmark were just children.

"I never imagined I'd be meeting up with the guy who [shot down his dad's plane]," he says. "All these guys - they were just kids. But it's stuck with them."

Contact Clint Cooper at ccooper@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6497. Subscribe to his posts online at Facebook.com/Clint CooperCTFP.