When entering Karah Nazor's biology lab on the fifth floor of McCallie's Upper School, it's hard to decide which of the many exotic sights to pay attention to.

Near the lectern, a stuffed black bear is frozen in mid-lumber. Above a row of windows overlooking downtown, a taxidermied shark hangs from the ceiling, its tail permanently bent and toothy maw agape. A squirrel perches, seemingly pausing between nuts, on a shelf.

But the real showstopper is very much alive and constantly in motion. Under the watchful, brown-eyed gaze of a mounted buffalo head, a massive, burbling aquarium swarming with jellyfish sprawls along an entire wall.

In the larger of two tanks, brownish upside-down jellies, looking like globular suction cups, cling to the walls or swim ceaselessly downwards against a carpet of smooth, dark-blue stones. Some are the size of dimes, the larger ones more like gold doubloons. One wall is covered in a layer of juveniles so dense that individuals are hard to pick out.

In a separate tank to the right, a smaller group of moon jellyfish move lackadaisically in an invisible, circular current. Larger than their topsy-turvy neighbors, the moons' ghost-like, translucent bodies are illuminated in lurid, ever-changing hues by a strip of multicolored LED lights installed behind the tank.

The sight of such a teeming marine ecosystem in a classroom isn't just surprising, it would be all but impossible at most schools thanks to the unique demands of raising jellies in captivity. But through a partnership forged with the Tennessee Aquarium, Nazor and 10 of her students have joined the paper-thin ranks of amateur jellyfish wranglers.

"Per capita, I'd say McCallie has more people than anywhere else in the world that know how to take care of jellyfish, especially considering that we're landlocked," Nazor says, laughing, as the aquarium tank's "snorkel" aerator filter makes rude gurgling noises in the background. "I'm not sure how many other people in Tennessee are regularly getting stung by jellyfish."

Getting the jellies into the tanks was a complicated, occasionally trying process, and it was primarily student-led, from designing the tank to raising the jellies' food -- microscopic animals and brine shrimp percolating on a nearby table in repurposed Simply Juice bottles.

Through their efforts, Nazor, the daughter of Times Free Press reporter Karen Nazor Hill, and her students have raised a bloom, also known as a "smack," of more than 1,000 jellies. The students are earning school credit from the booming swarm by caring for them and studying them in what Nazor describes as "graduate-level" research projects.

LEARNING THE ROPES

Before they would let a group of high schoolers take on the complicated task of raising jellyfish, Tennessee Aquarium officials wanted to ensure the animals would be suitably cared for.

Last summer, Nazor spent a month volunteering at the aquarium under the tutelage of Sharyl Crossley, a senior aquarist who oversees the Jellies: Living Art exhibit. When approached with Nazor's plans for taking jellies to McCallie, however, Crossley says she wasn't confident of the program's prospects.

"I was pretty skeptical. Jellies are tough to keep," Crossley writes in an email. "I still face challenges keeping them after more than nine years of experience. Combine their difficult nature with trying to keep them in a school setting with holiday breaks, weekends away and summers off won't work with animals that require a high level of consistent daily care."

But after some initial discussions with the students and a visit to McCallie to take a closer look at the set-up, Crossley OK'd the idea and a small shipment of jellies arrived at the school in November. Through updates she has received in the last few months, Crossley says she feels her confidence in Nazor and her students was well-placed.

Aquaculture -- the cultivation of aquatic plants and animals -- is becoming more popular in high school classrooms, she says, but projects that involve caring for jellyfish are -- quite literally -- a rare breed.

"There are some local schools with agriculture programs that also incorporate aquaculture in hands-on studies, but McCallie is the only one that I know of that is doing jellies in the classroom locally and doing them successfully," she says.

"I'm always available if they need me to troubleshoot something ... but they have everything going really well and don't call me too often," she says. "The projects and experiments that they are doing and have proposed are incredible. Most are beyond my expertise. It really is impressive."

TANKED

The challenges of the project began lining up for Nazor and her students months before their future gelatinous charges arrived at McCallie.

In late 2012, Nazor began considering alternate uses for her classroom's 75-gallon aquarium tank, in which students had been raising and studying Oscars, a species of freshwater fish. Moving on to another species of fish of the scaled variety seemed too prosaic, however, so Nazor decided she and her students would try their hands at something a little more exotic.

When she settled on jellyfish, her goal was to create a sustainable colony that the students could use to conduct multi-year studies. Generating a few knockout science fair projects along the way would be a nice bonus, she says.

However, before they would ever get the chance to lay hands on the jellies -- earning itchy red welts on their arms in the process -- the students needed to create a suitable habitat for them. That's when the first glaring problem reared its head, Nazor says.

"I quickly realized I was in over my head because jellyfish tanks were not commercially available," she recalls. "I didn't have the skills to construct one."

Fortunately, she says, one of her students did.

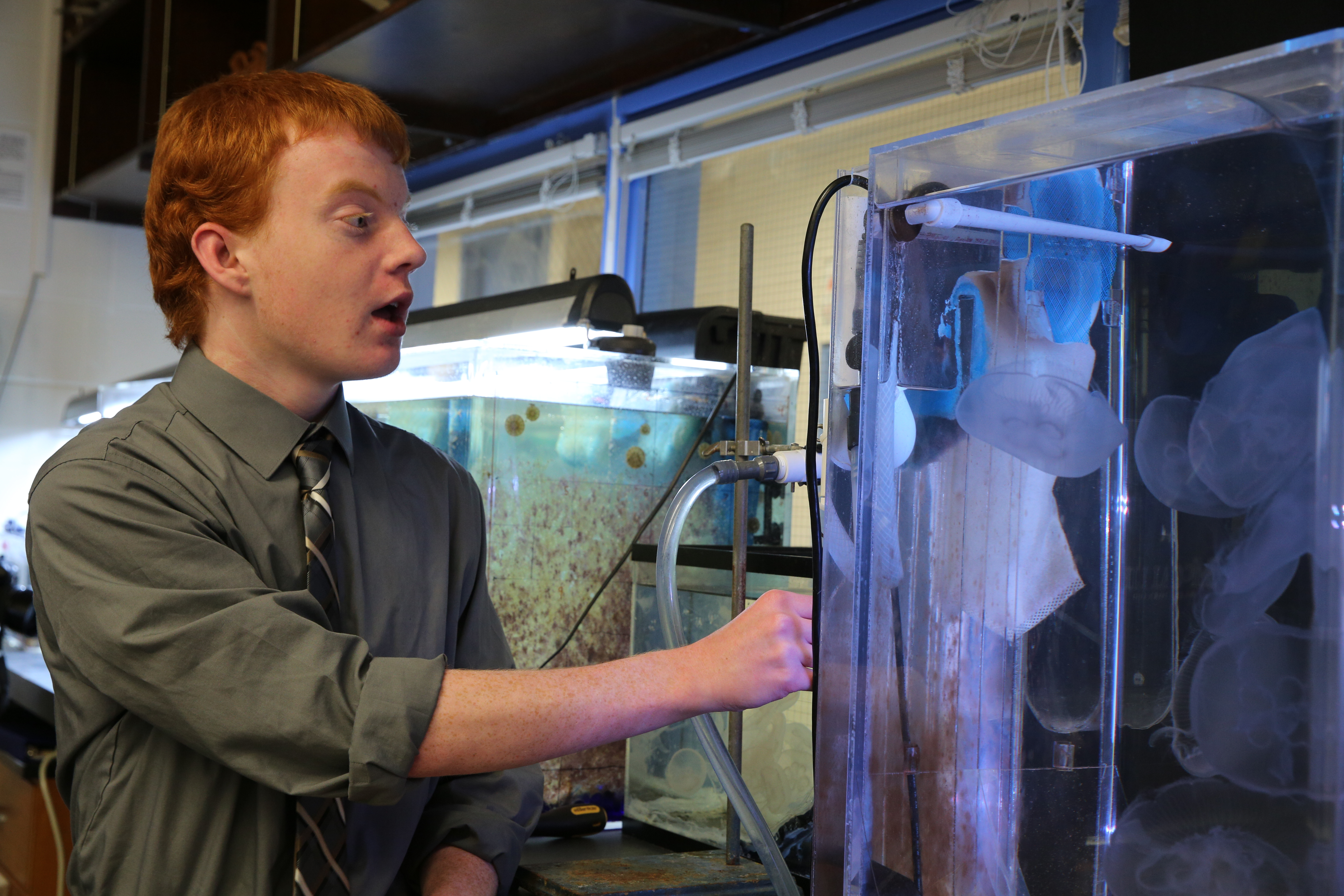

Philip Zeiser, then a junior, was asked if he was interested in earning some extra credit by building the tank. He agreed and began working through a snarl of engineering doglegs.

In addition to designing a jellyfish-friendly saltwater filtration system, Zeiser also needed to work out a construction blueprint for a kreisel, a specially designed tank with a curved strip of acrylic that helps replicate the ocean currents moon jellyfish rely on to move. The upside down jellies tank lacks this current since they are more powerful swimmers.

"I did research in those areas and, once I was certain I'd be able to figure it out, that's when we ordered the parts," says Philip, a soft-spoken senior wearing a tie depicting the periodic table of elements.

With the blessing of McCallie administrators and funding from the school, Nazor set Philip to work on the tank and an accompanying water chilling system that could keep the moon jellies' 46-gallon aquarium at the frigid 55 degrees they thrive in. Another student, junior Andrew Burkus, designed and installed an LED light system to ring the tank, partly to add a bit of sci-fi panache to the setup but also to fuel a potential project studying how jellyfish react to light patterns.

SCHOLARLY EXPLOITS

Nazor allowed the students' to design their own research projects, and their studies are as ambitious as they are varied. Some are even attracting attention in the greater scientific community.

Junior Chris Kositzke is attempting to artificially splice a segment of DNA from another species of jellyfish into the moon jellies in hopes of studying how their neural net -- the jellyfish equivalent of a brain -- develops. Through his research, he connected with molecular biologist Dr. Takeo Katsuki at the University of California at San Diego, who Kositzke says is awaiting his results to see if they apply to his own research.

In what some organizers called a "jellyfish invasion," Nazor's students converged on the Chattanooga Regional Science and Engineering Fair on March 10-13 at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga to share the findings from their research, even though some of their projects are still in the early stages.

There, freshman Andrew Aultman won third place overall for his study of photosynthetic bacteria in the tissue of the upside down jellies. He will advance in May to the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair in Los Angeles.

By allowing the students to guide their own research and learn from their failures and successes, McCallie's academic dean Sumner McCallie says Nazor has helped her students see that science isn't relegated to textbooks and pre-designed labs. In a sense, he says, the students are learning that they can do more than just listen to the great scientific conversations; they can contribute to them, too.

"That's a pretty powerful thing for a high school student to realize," McCallie says. "It's not just confidence in what they know and how well they can do on a test; they realize that they can take what they know and give back to the academic world."

NOT OVER YET

Despite the hassle of monitoring water quality and sipping countless inadvertent mouthfuls of brine shrimp through the siphon during feeding time, Nazor's students say they have yet to tire of the jellies.

Since many of her students are boarders and will be away for the summer, Nazor says the adult jellyfish will be returned to the aquarium at the end of the semester. There, they initially will be placed in an off-exhibit holding system but, depending on their size and condition, Crossley says they eventually may be placed on public display with the aquarium's other jellies.

Although some of the jellyfish are facing many more months of demanding care and research, the students say the rarity of the opportunity they've been afforded is worth the effort -- and a few stings for their trouble.

"This is something incredibly, incredibly few high school students ever get to participate in, especially at the scale we're doing," Kositzke says. "This is quite literally a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, and being able to do that in high school is incredible."

Contact Casey Phillips at cphillips@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6205. Follow him on Twitter at @PhillipsCTFP.