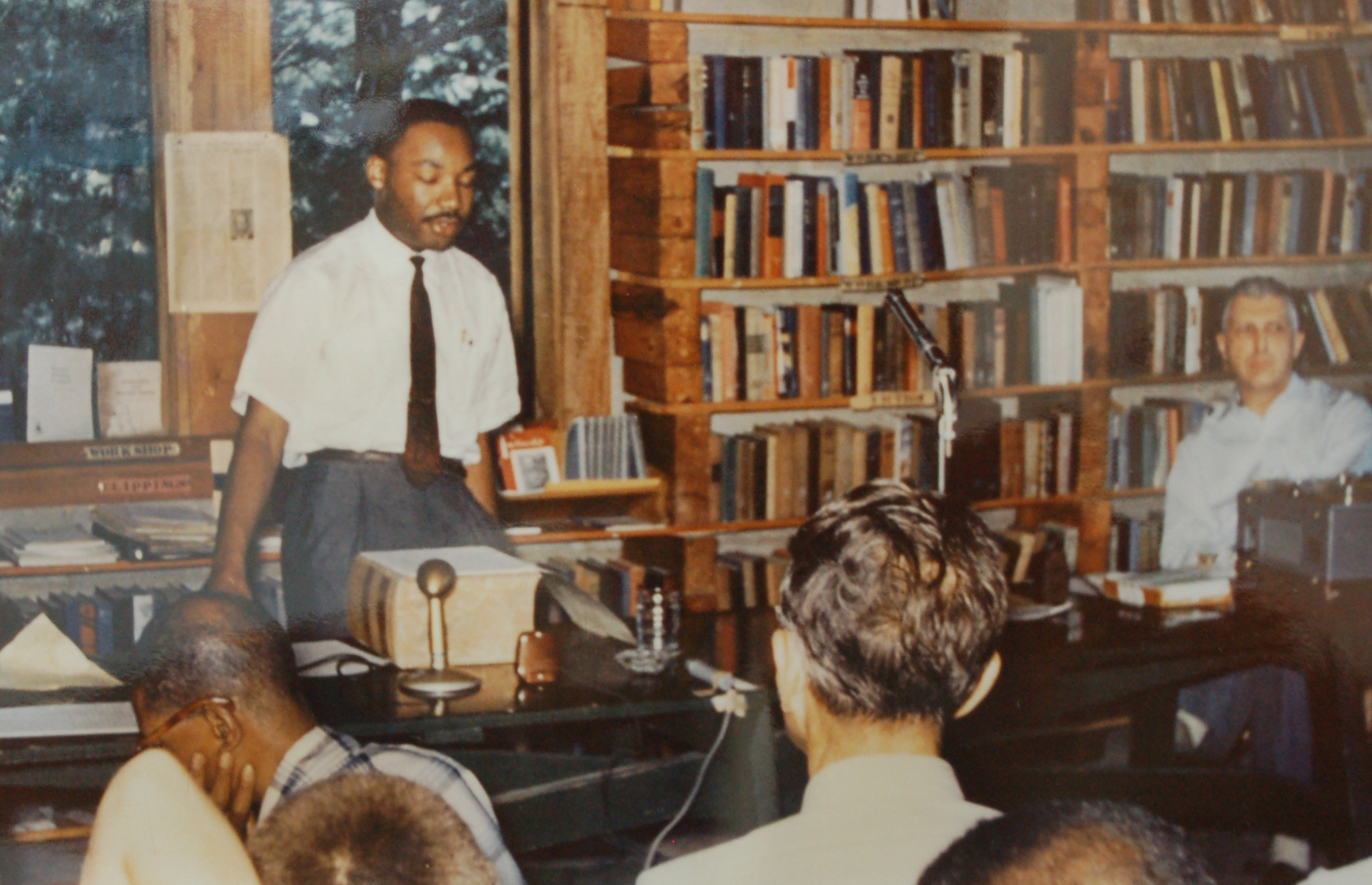

The Tennessee Preservation Trust has listed Monteagle, Tenn.'s Highlander Folk School on its Ten in Tennessee endangered properties list for 2014. The school library building, shown here, is where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks heard folk singer Pete Seeger's freedom anthem, "We Shall Overcome," for the first time and where many civil rights-era activists trained and discussed problems and solutions.

The Tennessee Preservation Trust has listed Monteagle, Tenn.'s Highlander Folk School on its Ten in Tennessee endangered properties list for 2014. The school library building, shown here, is where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks heard folk singer Pete Seeger's freedom anthem, "We Shall Overcome," for the first time and where many civil rights-era activists trained and discussed problems and solutions.TEN IN TENNESSEEThe historic sites named to the Tennessee Preservation Trust's 2014 Ten in Tennessee List of Endangered Historic Properties (three mills on the list are shown separately below) include:• Fort Wright Historical Site, Burlison, Tenn., in Tipton County was the first Confederate Army fortification built at Randolph and contains the only surviving Civil War powder magazine that can support public visitation. It is threatened by erosion, damage and roof problems.• Westover School, Union City, Tenn., in Obion County was built in 1879 and is locally important as a contributing member of the Washington Avenue and Florida Avenue Historic District. It is threatened by demolition, code failure and vandalism.• Interstate Life Insurance building, Chattanooga, was built in 1950 and is a beautiful example of architecture of the middle of the last century. It represents the growth of the insurance industry in Chattanooga and is now threatened by development.• Old Natchez Trace, Franklin, Tenn., in Williamson County was built around 1800 and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It is the oldest road in continual use in Tennessee and the United States, and at one location is home to 182 stone-box graves of Mississippian Indians. It now is threatened by development.• Gilley's Hotel, Bulls Gap, Tenn., in Hawkins County was built in 1920 and is significant in the Bulls Gap Historic District. It was important to the period when the railroad was the primary source of transportation. It is threatened by vacancy, water damage and roof damage.• Athenaeum Rectory, Columbia, Tenn., in Maury County was built in the 1850s and is all that remains of the Athenaeum Girls' School that thrived from 1852 until the early 1900s. Women there learned the same things men would have learned at the time. It is threatened by deterioration and lack of funding.• Model Mill, Johnson City, Tenn., in Washington County was built in 1909 and was critical to the industry in the area in the early 20th century. It is an example of general construction techniques of the time and is threatened by new development and deterioration.• Bemis Mill, Jackson, Tenn., in Madison County was built in 1901 and was the first industrial land bought by the county. By 1950 it employed 1,400 people. It closed as a cotton mill in 1991, and is threatened by new development and demolition.• Little River Lumber Mill, Pond and Railroad Yard, Townsend, Tenn., in Blount County was built in 1901, founded by Col. W.B. Townsend, the man for whom the town is named. The company built more than 150 miles of railroads in the Smoky Mountains from which the 560 million board feet of timber was sawed. It is threatened by new development.• City of Nashville, Tenn., in Davidson County -- the historic downtown area -- was founded in 1779 and contains many historic resources that are threatened by deterioration, development and a lack of restrictions by local government in the face of new interest by developers looking to invest in business opportunities.• Dr. Thomas Price House, Covington, Tenn., in Tipton County, was built in 1915 by the well-respected black physician and surgeon. The craftsmen/bungalow-style house has distinctive architectural details and is threatened by abandonment, neglect, termites and vandalism.• Gov. A.H. Roberts Law Office, Livingston, Tenn., in Overton County, was built in 1885 by the then-judge who served as governor when the Tennessee General Assembly in 1919 granted women the right to vote for municipal officers and for the president and vice president of the United States. Tennessee was the first southern state to pass such an act in its Legislature. The structure is threatened by natural wear, termites and potential demolition due to neglect.Source: Tennessee Preservation TrustHIGHLANDER TODAYThe school in Monteagle was moved after the state closed it in 1961, first to Knoxville then to New Market, Tenn., where, as the Highlander Research and Education Center, it continues to fight for justice and equality. Highlander officials call it a place where leaders, networks and movement strands come together to interact, build friendships, craft joint strategy and develop the tools and mechanisms needed to advance a multiracial, intergenerational movement for social and economic justice in our region. Learn more at the organization's website at highlandercenter.org.

MONTEAGLE, Tenn. - The Highlander Folk School on Monteagle Mountain is steeped in some of the most important times in American history, figuring prominently in organized labor efforts in the South and as a training ground for leaders of the civil rights movement.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks first heard folk singer Pete Seeger sing "We Shall Overcome" in the school's tiny, rustic library in 1954, when the first civil rights workshops were being held for activists who spoke quietly of a movement that would shout at the world.

It was branded King's "Communist training school" by the Georgia Commission on Education; targeted by a congressional Senate security subcommittee, IRS and FBI investigations; and padlocked by the state of Tennessee, which seized and later sold the buildings and land.

Now the Highlander Folk School, once part of a 200-acre campus, is threatened by time, deterioration and development, and the Tennessee Preservation Trust has listed it among Tennessee's 10 endangered properties for 2014.

The Trust's "Ten in Tennessee" list is its "strongest advocacy tool" for saving the state's most endangered historic sites, according to officials. But there's no safety net for Highlander, though the trust has purchased three tracts of the original property, including the library site.

"It's probably one of the top four or five historic sites associated with the civil rights movement in the country," said David Currey, chairman of the trust's board of directors.

"What's important about Highlander, one of the things they did there was bring blacks and whites together, and they're learning from one another how to organize," Currey said.

The people who trained there had strong characters and great courage, he said.

"When Rosa Parks was asked what Highlander meant to her she said, 'Everything,'" Currey said.

"Once these places like Highlander and the other properties on the list are lost, it's impossible to reclaim them," he said. He added that fundraising to buy more parcels will begin next year.

From 1932 to the mid-1940s, under founder Myles Horton, the school's mission was to build a labor movement that supported unionization. Over the years, Horton gained the support of Eleanor Roosevelt, United Nations Undersecretary Ralph J. Bunche and others.

The school's activities galvanized opponents in the 1930s and '40s, when coal mining was king in the area, and for its civil rights activists in the 1950s.

In 1936, a local resident wrote to FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, outing the school as a home to Communist-minded radicals. The writer's name is redacted from the manuscript kept at the Grundy County Historical Society.

"This school is a hot-bed of communism and anarchy. This is proven by the part taken by its members in the strikes at Harriman, Tenn., Daisy, Tenn., and at the present at Rockwood, Tenn. It is the opinion of the writer that this school should be investigated," the author wrote.

More controversy came in the 1950s as the push for desegregation became more formidable and King and others -- a list that includes early activists Septima Clark, Ralph Abernathy and James Bevel -- met to discuss ways to change society, according to accounts at the Grundy County Historical Society and historian and president Oliver W. Jervis.

Jervis said that whatever happens with the buildings, Horton's original ideas will always linger.

Just as Horton said when Grundy Sheriff Elston Clay padlocked the Highlander Center's doors in 1959 following an investigation by the General Assembly, "You can padlock a building, but you can't padlock an idea," Jervis said.

Horton's initial idea in founding the school was to carry on the ideas of Dr. Lillian Johnson, who donated the property for the work, Jervis said. Johnson wanted to help people, like the bugwood cutters in the little Summerfield community surrounding the school, fight for better wages. Bugwood is the junk wood left over after a forest is cut, and was harvested to make wood alcohol.

That inspired a work of art featuring Grundy County worker Billy Thomas that pressed for action and Thomas' quote, "It takes a sharp axe, a strong back and a weak mind to cut bugwood for $1 a day. Let's strike."

That small campaign didn't work, but it established the idea of how to organize for labor equality, Jervis said.

Highlander's approach to adult learning focused on community members working together to identify problems and find solutions themselves, he said.

"It's a bottom-up approach," Jervis said. "That's as important an element of Myles Horton's life as anything."

The same approach was used in solving racial issues in workshops that drew the likes of King, activist James Lawson and Parks. It was just a few months after her training at Highlander that Parks took her seat on the bus in Montgomery, Ala., and refused to give it up, initiating a new era in American history.

Jim Lewis has lived next door to the library building for 21 years and has seen busloads of visitors arrive from as far away as Chicago to see it. Lewis has helped keep up the property and worked with other local people to clean it up after the Tennessee Preservation Trust bought it.

Lewis said he's glad the trust is preserving the structures but he isn't looking forward to more traffic on the one-lane, chip-and-tar road where his home and the library building stand.

Chattanooga resident Roger Vredeveld on Thursday was scouting bicycling routes and decided to try to find the well-hidden little library building while he was in the area.

Vredeveld, who retired from teaching at Baylor School in 2013, said the Highlander properties were "a very special place" connected with those who promoted nonviolent change throughout the South.

"I'm excited about the restoration of this site," he said while standing beside Horton's grave at Summerfield Cemetery, "because it's extremely important to civil rights history."

Now, with a fresh coat of white paint on its concrete block and clapboard exterior, Highlander awaits its next step in history.

Contact staff writer Ben Benton at bbenton@timesfreepress.com or twitter.com/BenBenton or www.facebook.com/ben.benton1 or 423-757-6569.