Chattanooga's history as a gritty city populated by daring entrepreneurs who bent steel and and built banks was written by businessmen like Harry S. Probasco and Jim Steffner.

The two business leaders on Thursday will be elevated to UTC's Entrepreneurship Hall of Fame, which boasts a membership list that includes a who's who of the region's best and brightest business magnates. Since its creation in 1999, the Hall of Fame has inducted 51 business pioneers like Probasco and Steffner.

Probasco, a banker, and Steffner, an industrialist, worked from opposite ends of the financial world to create jobs and build wealth. One was a money man who made the loans necessary for companies to expand capacity and hire more workers. The other saw needs in the world and created products that solved problems.

Both had fathers who helped ease them into the family trade. Both made a mark as men of God at First Presbyterian Church. Both left the family business in the hands of trusted sons. And both helped grow Chattanooga into a town that, by its bustling business climate, earned the moniker Dynamo of Dixie.

•••

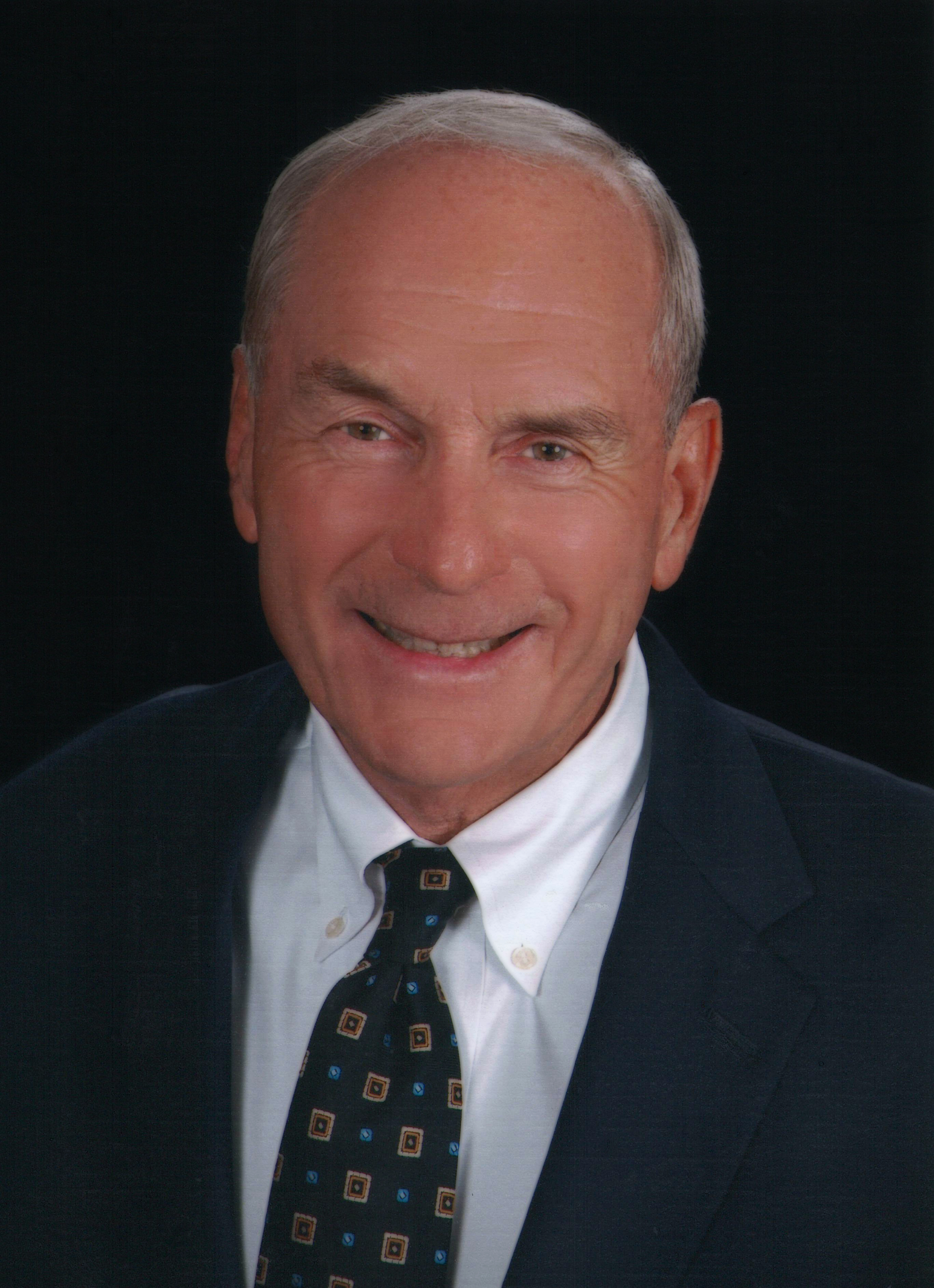

JIM STEFFNER

Jim Steffner never doubted that he would join the family business.

On his 13th birthday, which fell on April 30, his father, Samuel Steffner, presented him with the gift of hard work.

"Daddy bought me a gasoline lawnmower for my birthday," Steffner remembered. "He said if you want money, you go earn it. I got six yards that summer, I had a gas can and I went around cutting grass. That was my first business. I didn't think about why or what I was doing, I just enjoyed doing it. I liked making things happen."

More than 50 years later, Steffner can look back at a long career of hard work, a handful of businesses he founded and sold, and a lifetime of building widgets for businesses ranging from Dalton, Ga.-based carpet mills to international giants like General Electric.

The family has two mainstay businesses: Chattanooga Armature Works and Electric Motor Sales & Supply.

The whole venture began in 1890, built as a bicycle business created to take advantage of what was then a bicycle craze. That company lasted until Steffner's great grandfather, Frank Steffner, who had a mechanical mind, began helping to repair streetcar motors out of the shop during a streetcar strike.

Frank Steffner's new job was to help rewind the electric armatures, which is the motor or generator of the car. Thus, he found himself in the electric components business and soon renamed the company to Chattanooga Armature Works.

Jim Steffner, his grandson, joined what was by then a successful business in 1964 doing $2 million per year in sales. At first, he didn't really fit in at Chattanooga Armature Works.

"I had just came out of army as a first lieutenant and I was all charged up," Steffner said. "It was a disaster. I didn't want to work with them, and they didn't want to work with me."

So he went to work at the family's other business, Electric Motor Sales & Supply.

"I walked in one day and said, 'Daddy, if you don't mind, I'd like to have a job working [at EMS].' He said, 'I don't mind, how quickly can you get over there?'"

Steffner learned how to sell during his first assignment in Dalton, Ga., which was then an emerging mill town. He found that carpet makers there really needed a variable speed DC drive, which the company was able to create.

That sale in 1968 led to the founding of the first of several businesses that would spin out of the family's portfolio, Electric Systems Inc., which Steffner sold in 1999. The company found customers throughout the carpet and textile industry, eventually selling $20 million worth of equipment to manufacturers per year when it was sold.

In 1972, he founded Metal Systems Inc., which builds control panels for Fortune 500 companies like Siemens and GE. Metal Systems, which eventually grew to about 350 workers, was one of the first companies in the 1980s to implement a strict quality control program.

"We had four people who did nothing but quality work," Steffner said. "This was so impressive to people like GE, Siemens, it gave them a good feeling. Metal systems had a system of producing quality, and that's what enabled the thing to grow so well."

Metal Systems, which the family later sold, became the largest system center builder in the U.S., and helped contribute to a combined annual revenue for both companies of $136 million.

Even after the sale of both companies, Steffner isn't hurting for business. Electric Motor Sales still pulls in $50 million in revenue per year, with locations in Chattanooga; Cleveland, Tenn.; Knoxville; Kingsport, Tenn., Dalton, Ga., and Cartersville, Ga.

Steffner says his secret to success is surrounding himself with good people and making decisions as a team. He also made sure not to bet the entire company on any one decision.

"You make a lot of mistakes," he said. "I tell you what I tried to do was rely on people who knew more than I did. The worst thing you can do is make too many decisions without getting some advice."

Though he's not currently starting up any new businesses, he's spending more time in the office than ever with his son, Jamey Steffner, CEO of EMS, and he's working with partner Gary Chazen of Perimeter Properties to market the former U.S. Pipe and Wheland Foundry site to major developers.

"My back is so bad I can't play golf anymore," he said. "All I can do is play around here at the office."

•••

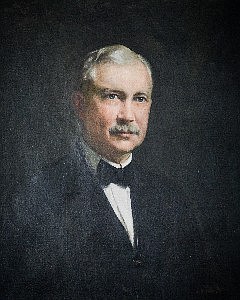

HARRY S. PROBASCO

The Probascos have been bankers since the 16th century, when they were forced to flee Madrid to escape persecution by Catholics. They moved to Holland, then immigrated to New Jersey, then to Ohio, Indiana and finally settled in Chattanooga, where Harry S. Probasco founded the Bank of Chattanooga, which later became American National Bank.

It didn't start out as a walk in the park.

Probasco got his start in banking at the age of 17 at the People's Bank in Lawrenceburg, Indiana, going to public schools there and then studying at Earlham College. His father owned the bank, and paid him with experience rather than a salary.

After the river flooded and damaged the town in 1884, Probasco left and settled in Chattanooga.

In 1888, finding six banks but none that handled trusts, he founded Wiehl, Probasco & Co., hoping that business owners in Chatatnooga would entrust him with their wealth. Over time, they did.

It was a period of economic ups, downs and panics. Probasco and Fred Wiehl took over the Fourth National Bank during one such panic, changing the name of the combined entity to the Bank of Chattanooga in 1990 with Probasco as president.

During the economic hardship that followed, Probasco in 1905 formed a new bank, the American National Bank, with an initial investment of $250,000. He sold what had become a profitable bank in 1911 to First National Bank, agreeing to stay out of banking for one year.

Suffering from ill health, he took a year long trip to Europe. When he got back, he met with friend Ben Thomas, who had founded the Coca-Cola Co., and the two decided to found yet another bank.

With Coca-Cola money behind the founders, and a board that included E.Y. Chapin and Probasco's son, Scott L. Probasco, the bank opened in 1912 as American Trust and Banking Co.

Probasco died a few years later in 1919, but his legacy endured through his heirs and through the institutions that he founded. Scott L. Probasco took over for his father as president of the Union Cotton Mills in LaFayette, Ga., fought in two world wars and became chairman of the board of American Trust and Banking Co. in 1941.

In 1948, the bank transformed into American National Bank. Probasco remained as chairman, and was succeeded by his son. Scott "Scotty" Probasco Jr.. Under his tenure, the bank became part of Third National Bank and later Suntrust. Probasco Jr. still maintains an office at the bank. The Probasco Chair of Free Enterprise at UTC is named in his honor.