Since its creation in 1935, the Electric Power Board has been owned by and its debt issued from the city of Chattanooga, which chartered EPB as a non-profit agency 80 years ago and continues to appoint the 5-member board that governs the municipal power distributor.

But EPB's governing board is an independent body; EPB by law must be self-financing through its own electric and telecommunications rates, and its rates and payment schedules are regulated by the Tennessee Valley Authority. In October 2009 as EPB was preparing to expand its telecommunications business and seek a federal stimulus grant of more than $111 million, EPB also filed papers with the Tennessee Secretary of State to reaffirm its charter as a non-profit corporation.

So is the EPB simply an branch of City Hall or its own corporate identity? The answer is key to whether a a multi-million lawsuit filed against EPB on behalf of the city by a former city contractor can proceed in court.

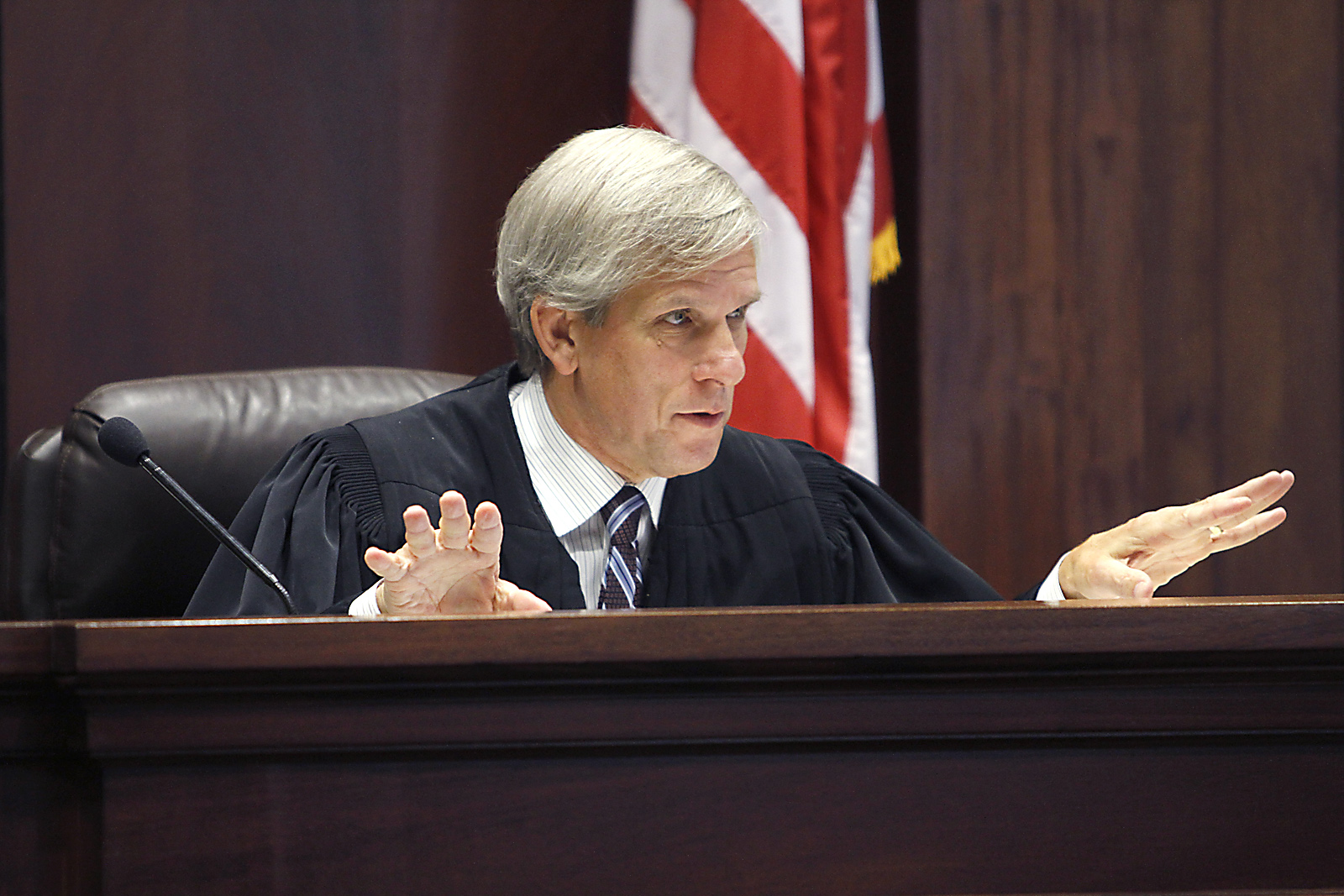

After months of arguments and thousands of pages of briefs and testimony, Hamilton County Circuit Court Judge Jeff Hollingsworth promised Monday to decide on the legal status of EPB.

Don Lepard (CQ), CEO of Global Green Lighting, is photographed on the Walnut Street Bridge in downtown Chattanooga. His company has developed an energy-efficient lighting system that can be monitored and controlled through the internet. His lights have been installed on the Walnut Street Bridge, in Coolidge Park and along Frazier Ave. in North Chattanooga.

Don Lepard (CQ), CEO of Global Green Lighting, is photographed on the Walnut Street Bridge in downtown Chattanooga. His company has developed an energy-efficient lighting system that can be monitored and controlled through the internet. His lights have been installed on the Walnut Street Bridge, in Coolidge Park and along Frazier Ave. in North Chattanooga. "We have a legal dispute and that is something that I am going to have to decide upon," Hollingsworth said after hearing oral arguments in court Monday. "I'm going to take another look at it and resolve this issue of law."

Last month, Hollingsworth issued an opinion suggesting that a jury trial might be required to determine the legal status of EPB. But on Monday, the judge said he now recognizes the question as a legal one he must decide, not as a factual determination to be made by a judge or jury in a separate trial.

Hollingsworth's opinion will either quell the attempt to sue EPB for its alleged overbilling of the city for its streetlights or allow a lawsuit against EPB to move forward by Global Green Lighting CEO Don Lepard. The plaintiffs want to require EPB to refund payments to the city and share some those city savings with Lepard for uncovering the incorrect billing for the city.

If Hollingsworth rules that EPB is a part of the city as the utility claims, then the lawsuit can't proceed since it would then mean the city was trying to sue itself and would violate the sovereign immunity protection for a city agency.

But if Hollingsworth says EPB and the city are separate, then Lepard, on behalf of the city, may sue to collect on overcharges from EPB to the city.

"We look forward to the court's ruling on the issue so we can move on to the issue of overcharges and the amounts due Chattanooga taxpayers," Lepard said after the court hearing.

Lepard sued EPB in July 2014 under the state's False Claims Act to reclaim a portion of what he claims EPB overcharged the city for streetlights. Lepard says his company's count of streetlights he was replacing found the city had been using and billing upon wrong numbers and types of lights in its 600-square-mile footprint.

"The bills were false in that they billed excessively and contrary to EPB's contract for energy consumed by inefficient old lights which had long since been retired and taken out of service," Jay Barber, the Atlanta lawyer who filed the lawsuit for Lepard, said in his initial 33-page complaint against EPB.

EPB concedes that many streetlights were incorrectly classified. But a study done by EPB auditors suggests that any overcharges for lights that were not on poles is offset by undercharges from other lights that were improperly listed or not counted.

EPB doesn't meter its streetlights but relied upon estimates about energy use based upon the type and number of lights.

Lepard was hired by the city to install more energy-efficient LED lights and to do so with with controllable devices to allow the lights to be raised or dimmed as required for crime fighting, special events and energy efficiency.

In March 2012, then Mayor Ron Littlefield and the city agreed to purchase up to 27,000 lights from Global Green Lighting. The contract staggered the work, however, and the city was obligated only to buy the first $6 million of lights n the first year.

The city bought 6,134 lights and 5,000 were installed before Mayor Andy Berke decided not to continue with Lepard's replacement light program.

Before any lawsuit moves ahead, however, Hollingsworth must decide that EPB is not part of the city for purposes of the False Claim Act or that EPB doesn't enjoy the sovereign immunity protections of the city, which assert that the King, or in this instance EPB, can do no wrong.

Lepard is suing as a whistleblower to help the city reclaim money he says it is due and to get a share of those savings as provided under state law.

Joan MacLeod Hemingway, a professor at the University of Tennessee College of Law, said an incorporation filing by EPA in 2009 indicates EPB has a separate legal standing from the city of Chattanooga.

"While incorporation does not change EPB's status as a board of the city of Chattanooga, it does establish EPB as a distinct legal entity with corporate status," Hemingway said in a court filing.

But EPB claims the filing did not change in any way EPB's status as part of the city. Kevin Rayburn, assistant director of the business service division with the Office of Tennessee Secretary of State, submitted a declaration to the court clarifying that EPB's filing "does not mean that a public governmental corporation or authority is, in fact, a private non-profit corporation.

"Rather, the use of the generic term "corporation" in the certificate of existence can, and does, describe public governmental corporations or authorities," Rayburn said.

EPB Attorney Rick Hitchcock said Rayburn's affidavit clarifying the incorporation filing by EPB "should end the frivolous argument (from Lepard) that EPB somehow " incorporated" itself by making a record filing of this state enabling legislation before the Secretary of State."

In Tennessee, at least 22 cities and government agencies, including the city of Cleveland, have made similar charter filings as nonprofit corporations with the Secretary of State, according to court filings. EPB President Harold DePriest said nothing in the 2009 filing changes EPB's status as a municipal utility owned by the city of Chattanooga.

Contact Dave Flessner at dflessner@timesfreepress.com or at 757-6340.