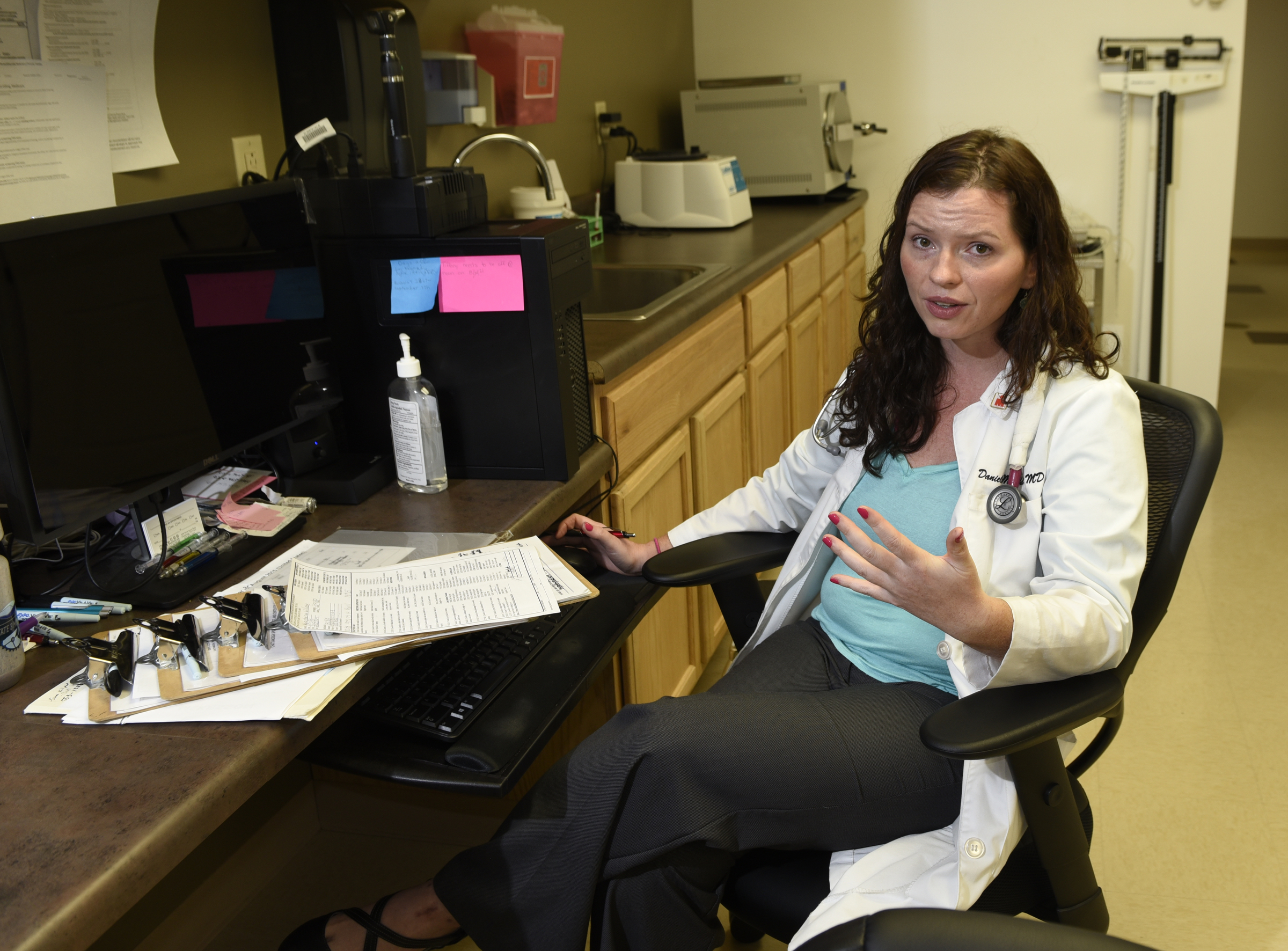

Dr. Danielle Mitchell doesn't have much love for insurance companies.

The Chattanooga physician says they drive up costs and limit doctors' time with patients. So Mitchell plans to cut ties with insurers by encouraging her health-minded patients to switch to high-deductible plans and pay out-of-pocket to see her more often.

"I can't get rid of insurance companies all at once," Mitchell said. "But I am definitely starting to phase out the insurance companies one by one."

Mitchell's patients can choose a "membership option" at her Chattanooga Sports Institute and Center for Health. For $50 a month, or $600 annually, they'll be guaranteed four, 30-minute office visits and reduced prices for X-rays, labs and urgent care services. Or patients can pay $60 for each 15-minute visit. Or, if they want to use insurance, Mitchell will see those patients for 15 minutes.

What you pay

Fees at Dr. Danielle Mitchell’s Chattanooga Sports Institute and Center for Health• Membership option: Patients pay $50 per month for one year, or $600 which entitles them to four 30-minute office visits and reduced costs on X-rays, lab and urgent care.• Pay-as-you-go: Patients pay $60 for each 15-minute block of time and also get a discount on service.• Insurance option: Patients can keep their current plans and will get 15-minute appointments.See more online at www.chattanoogasportsinstitute.com

Ultimately, though, she'd like to phase out all insurance companies - and figures she can make a go of it if 700 to 800 patients choose the membership option.

She's not the only doctor who'd like to get away from health insurance companies, even as the Affordable Care Act, or "Obamacare," mandates that every American must have health insurance.

"Over the last few years, there's been increasing interest and discussion about this as a model," said Rae Young Bond, executive director of the Chattanooga Hamilton County Medical Society, a nonprofit organization that supports and advocates for doctors.

Doctors elsewhere have made the cash-only model work.

It's most commonly known as direct primary care - a payment arrangement between patients or employers that doesn't involve billing insurance providers.

"You have to be a bit entrepreneurial. There has to be enough volume," said Dr. Jeff Huotari who opened a "micropractice" in 2006 in Houghton, Mich., that he recently sold to a hospital there.

Huotari is executive director of Ideal Medical Practices, a national nonprofit organization that helps small, independent practices collaborate on ideas for efficient, high-quality care, he said.

The model of a micropractice, or minimalist medical practice, was pioneered in 2002 by Dr. L. Gordon Moore of Rochester, N.Y., who opened a 110-square-foot office equipped with not much more than a stethoscope and a cell phone, Huotari said.

The idea is that by slashing overhead, doctors are free to spend more time with patients. For example, a micropractice typically sees one patient at a time, which eliminates the need for a waiting room.

"It's a legitimate movement. It's getting a ton of attention," said Huotari, noting that as many as 6 percent of physicians nationwide have some sort of direct primary care model.

Meanwhile, health insurers say that insurance helps lower prices.

"Our network of doctors, hospitals and other health care providers deliver services at lower rates that we've negotiated on behalf of BlueCross members," said Mary Danielson, director of corporate communications for BlueCross BlueShield of Tennessee. "Advocating for affordable care is a role we take seriously."

'It's going great'

The direct primary care concept has been endorsed by such mainstream organizations as the American Academy of Family Physicians, which offers doctors a "toolkit" to implement the model. The academy says direct primary care offers such benefits as decreased practice overhead, fewer medical errors, reduced patient volume and "zero insurance filing."

Another pioneer in the direct primary care movement is Dr. Brian Forrest of Apex, N.C., in the Raleigh-Durham region who was the focus of a 2010 article in Medical Economics Magazine titled "How to run a cash-only practice and thrive."

"It's going great," Forrest said Thursday. "We've been doing it, going on 15 years now, and I haven't had a contract with Medicaid or any insurer."

He said that cutting out insurance eliminates $250,000 in overhead annually for the average physician, which allows direct primary care doctors to cut prices by 80 to 85 percent. Forrest views his low-overhead, membership-model micropractice in which patients pay a monthly fee as "kind of like a gym membership for your healthcare."

Forrest helped found the annual Direct Primary Care Summit, which in July drew more than 320 participants to the Kansas City area. He said he's helped more than 500 medical practices around the country adopt the direct primary care model.

"Is Obamacare going to kill the model? Absolutely the opposite," Forrest said. Employers who contract with direct primary care physicians can save about 30 percent on their premiums, he said, and employees who've seen their deductibles soar under the Affordable Care Act can benefit, too.

"We tell them high-deductible plans work really well with it," Forrest said.

Independent physicians can spend more time with patients, said Dr. John Standridge, a longtime Chattanooga M.D. who owns his own practice and doesn't get a salary from a hospital.

"Employed physicians are not the best for the healthcare system," Standridge said. "They're under the thumb of the number-crunchers. They have to see X number of patients per hour. Complicated patients take a lot more than 10 or 12 minutes to process."

"I have known a number of doctors who have been called on the carpet and fired because they're not fast enough," he said.

Mitchell thinks dealing with health insurance companies is more trouble than it's worth, partly because she has to hire people to fight insurers over billing.

"None of [the insurance companies] are easy to work with," Mitchell said.

That's a common complaint among Chattanooga-area doctors, according to Bond.

"Every individual practice has had to add significant numbers of staff to deal with billing issues," she said.

'5 minutes not enough'

Mitchell mainly wants to spend more time with patients.

She underwent a personal transformation from morbid obesity, or 250 pounds on her 5-foot, 6-inch frame, to a lean triathlete. Mitchell thinks insurance companies partly are to blame for what she calls the "sick care" model of medicine in which physicians don't have enough time to interact with patients.

"We're not taking care of people," Mitchell said. "We're essentially putting Band-Aids on stuff."

Mitchell counsels patients on diet and exercise. For example, one of her patients had been prescribed three medications after her doctor told the woman she was going to get diabetes. Mitchell said she "got her on a program of healthy activity and nutrition, and within four weeks, she had lost 17 pounds, her blood work looked excellent, and she is not any medicine."

A doctor may see 30 or 40 patients a day, Mitchell said. Patients often have to wait for weeks to see their physician, and may have to wait again in the doctor's office. And when a patient finally sees a doctor, she said, it may only be for a few minutes.

"It's usually, on average, a five-minute experience," Mitchell said. "There is no way you can talk about true preventative health care in five minutes."

Mitchell thinks her model can save patients money, even with the $600 annual cost of a membership.

A broken arm would use up two of the four 30-minute visits, she said, and cost $30 for three X-rays and a $20 casting fee.

"So it's $50 out of pocket," she said.

She thinks she can make the out-of-pocket doctor's practice work, partly because she said she's not out to get rich and has "no Mercedes, no McMansion on the hill."

"You don't have to make a killing in life, you just have to make enough," Mitchell said, quoting poet and environmental activist Wendell Berry.

Contact staff writer Tim Omarzu at tomarzu@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6651.