In the early 19th century, pundits marked the time of death of artisanal crafts, which for centuries had been the sole method of creating the goods we'd come to count on, like clothes and furniture. The verdict? Murder. Killed by the Industrial Revolution, smothered by the lure of new machinery, trampled by a desire for efficiency. Gone. Obsolete.

Or so they thought.

Despite the ease of mass-produced products, the demand for original, one-of-a-kind creations by craftsmen and artisans has never completely dissipated - and neither have the artisans themselves. Though apprenticeships have turned to internships and marketplaces have become web pages, these lovers of their trades have endured the test of time.

Some have stayed true to tradition, some have evolved to fit the new era, but all are doing what they can to keep their craft alive.

You just have to know where to look.

THE LOWDOWN ON LEATHER: HASLERIG SADDLERY

Then and Now

Then: Since early hunters starting tanning, or converting animal hides and skin into leather, the material has been used to create everything from armor to footwear to, of course, saddles. For hundreds of years, horses were ridden bareback or with a piece of cloth or hide to serve as padding, but as longer periods on horseback yielded discomfort, the first saddles were developed. Most saddles were made with a "tree," a wooden frame designed to keep weight off the horse's vertebrae, which was then fitted with leather for cushioning, durability and aesthetic appeal. Now: While saddle makers no longer have to tan their own leather or build their own trees, David Haslerig says not much else has changed. What really sets his Western-style saddles apart from those made in the cowboy era is tooling. Custom-made saddles are often decorated with flowers, leaves or other patterns hand-carved into the leather with a swivel knife. Older saddles had larger, less-detailed designs, Haslerig notes, but as tools have gotten better, the artwork has become smaller - even as small as a dime - and more intricate. These same kinds of designs can be seen on Haslerig's other leather products, which include purses, belts, wallets, animal collars and more.

With the dominance of the automobile industry, saddle making may seem like a lost art, but from the privacy of their own homes, dozens of local leather workers are keeping the profession alive. Haslerig learned the basics from his father, but a high school rodeo stint kick-started his own love affair with leather.

David Haslerig: People think 'leather work' and 'rodeo' and they think Texas, out West. But at one point in time, Chattanooga was who built most of their saddles.

There's a big brick building right off the road if you're heading away from Chattanooga that says 'Southern Saddlery' on it. That was an old saddlery, and right across from it, they used to have Scholze Tannery, one of the best leather tanners in the U.S. at one point in time.

Then, you had Simco Leather Company, Crates Leather Company, Big Horn Inc., and there was the tannery with all these saddleries right around it. But then they closed.

Only one of them is still there: American Saddlery. It's one of the last ones left in Chattanooga.

But all those people who worked at those saddle shops went home and started doing it at their house, so there are still a lot of saddle makers right here locally. There's probably 20 or 30 within an hour's drive of here. But you'll drive right by their home and never know they have a shop behind the house.

My dad has a little shop where he builds stuff for people, and I had a little corner where I did my work. But I got to a point where I needed to move out of the garage and do this for real.

That isn't to say other saddle makers aren't doing it for real - they have raised kids and fed their families from the back of their garage. But I wanted to make it a brand, if you will, so I opened my building last January.

Some people have said I'm an artist, but I don't know. I guess you don't see yourself that way. It's just something I do. [laughs]

It all comes down to the way I tool. It doesn't mean I'm better than other people, it doesn't mean that I'm worse than other people, it's just different.

We get a lot of people that stop by and are just glad to see somebody doing this around here again. But they don't even know that there's people all over doing the same thing; they just don't have a sign out.

BREATHING NEW LIFE INTO GLASS: THOMAS SPAKE STUDIOS

Then and Now

Then: Today, anyone can watch a glassblower pull molten glass from a furnace and manipulate it into shape with a blowpipe, shears and tweezers, but the art of glassblowing was once Europe's best-kept secret. The technique was passed down exclusively from master to apprentice, and in the late 1200s, all the glassblowers in Venice were forced to move to the island of Murano to keep the process out of competitors' hands. Though the punishment for leaving the island was death, many glassblowers eventually escaped and passed the art on to others. Now: They may be modernized, but Thomas Spake says if you took a photo of the tools used to blow glass during the Renaissance and the tools used today, they would look "amazingly similar, if not identical." The largest difference, of course, is the secrecy - or lack thereof. The art once reserved for apprentices is now taught in colleges around the world, and glassblowers like Spake are making sure the techniques remain overt by teaching workshop classes for anyone who wants to learn.

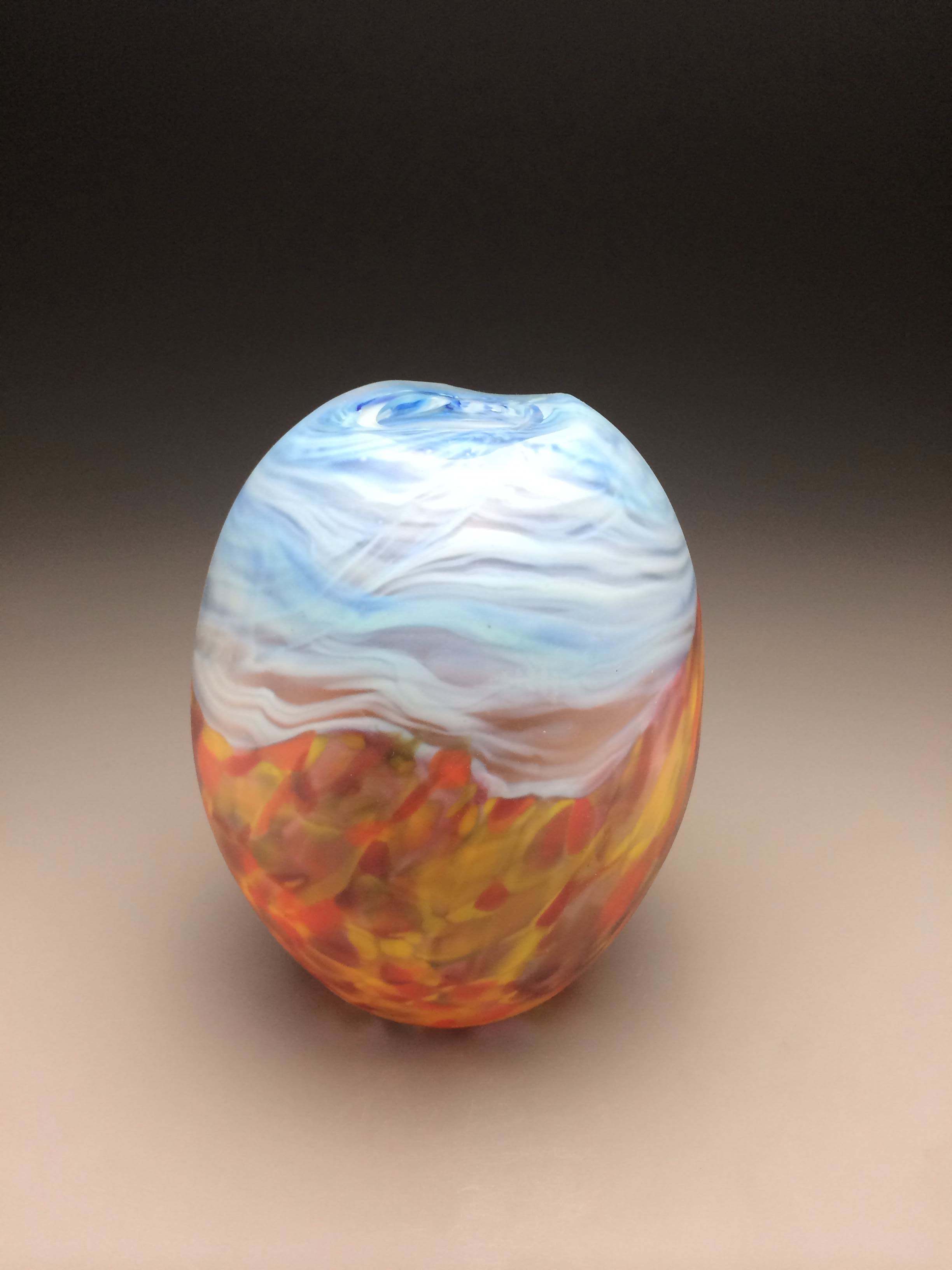

Everything about Spake's introduction to glassblowing was unconventional, but his atypical pathway to the art gave him the freedom to deviate from the ordinary and explore creative routes of his choosing. The results have made Thomas Spake Studios home to unique pieces that breathe new life into the craft.

Thomas Spake : I was always interested in art and did some painting and ceramics in high school, but I was also always tall and my father was my coach, so that kind of naturally led me into playing basketball.

I went to college to pursue a basketball career, but I had a work-study program in the art building. On the first day, I go up there, and I had to walk past the glass studio - and it stopped me in my tracks.

I'd never seen glass being made before. It's just such a jaw-dropping thing to see people playing with fire and molten glass. It was really hot and physical and kind of macho in a way.

I couldn't really do glassblowing because it interfered with practices and games, so I ended up quitting basketball my junior year. My dad's starting to get over it a little bit now. [laughs]

That whole transition kind of flipped a switch in my life. I wouldn't say I was a natural or anything like that; just really had to work really hard. I was kind of behind because I was starting the spring term of my junior year.

I've had an assistant here at my studio for the last year or so, but up to that point, I've kind of been on my own, which is unusual.

Equipment is really expensive, utilities are really expensive, so a lot of glassblowers share a space or rent it from other people who have a more established operation. They end up with a whole lot of influences telling them "You should do this, you should do that," and when you're starting out, you can be manipulated by people as opposed to following your own thoughts or opinions.

A lot of people want to make what the big glass makers out there are making, but I don't really care what everyone else is doing. To be an artist, you have to have a style that people notice as unique and different. The last thing you want is to be blowing glass for 10, 15, 20 years and everybody's says, 'I love your glass, it looks like so-and-so's.'

I would rather an idea to steer me to come up with a new technique that no one else has developed.

I've always liked to get outside and see natural beauty, and I've always enjoyed photographing waterfalls and mountain vistas and all the beautiful things out there. So I take the photographs and use those to inspire the work. In my work, you'll see whole landscapes or the idea of a waterfall. You'll see the light shining through the leaves of a tree or the ripples of water on the surface.

It looks very different from other glass. I'm using mostly opaque glass and I'm sandblasting the surface so it looks like pottery or stone or sometimes wood.

Most of my work is decorative. Besides being beautiful and maybe helping you remember a beautiful place you've visited, there's not really any function. It's kind of a harder path to pursue, but I want to be my own person and hopefully inspire other people with what I'm making.

MOLDING THE WORLD OF POTTERY: BEAN AND BAILEY CERAMICS

Then and Now

Then: Humans have been using clay and water to create various objects for millennia, but it wasn't until about 10,000 years ago that the materials were used to craft pots. As nomadic people formed communities, they found themselves in need of something to hold liquids to water crops. The resulting pottery vessels were created by stacking clay rings, smoothing them out, and firing them in kilns dug into the ground. Pottery remained undecorated until the Greeks got their hands on the craft and turned it into an art form, adding color and mythological characters to the clay. The potter's wheel eventually simplified the process by allowing craftsmen to turn the pots as they worked, and later models spun fast enough for them to drop a ball of clay onto the wheel and shape it as it turned. Now: Since pottery's inception, numerous ceramic forming techniques have been developed, but the method local potters Anderson Bailey and Jessie Bean use is slip casting. The technique, introduced in European porcelain factories in the 18th century, allows workers to mass-produce ceramic objects in shapes not easily formed with a pottery wheel. The process starts by creating a hollowed-out block of plaster to serve as a mold. Liquid clay (called slip) is poured into the mold and left to sit. Since plaster is a porous substance, it draws the moisture out of liquid clay it is in contact with, creating a layer of solid clay in the shape of the mold. When the solid clay reaches the desired thickness, the remaining liquid clay in the center is poured out, and the object, now in the shape of a cup or bowl, is left to harden before it is fired in a kiln.

While most modern artisans have avoided change, Bean and Bailey have embraced it - and they're hoping Chattanooga will do the same. Instead of crafting pottery the traditional way, by throwing clay on a wheel, the husband-and-wife team has adopted a newer, lesser-used technique to mold bowls, cups, vases and more into a clean, contemporary shape this city hasn't seen before.

Anderson Bailey: The process we use is called slip casting. It's only 100 years old, maybe. It's an industrial process that people started using more for studio purposes in the last 30 to 40 years, and especially more in the last five to 10 years.

Jessie Bean: Just four years ago, when we started slip casting, there were very few people you could even find that were doing it.

JB: It's different. Whenever we do a craft fair, that's the comment that we get. People walk in and they're like, 'Oh my goodness, this is like a breath of fresh air!' It's unusual to them. They haven't seen people actually making anything like it.

AB: No one I know of [is doing slip casting in Chattanooga].

JB: For a lot of the old-timers in ceramics, slip casting is so frowned upon. The problem is they never tried to make a bowl before and realize all that goes into the process and how it is just as handmade as them throwing stuff on a potter's wheel.

AB: The designing - physically building those models - that's the craft side.

AB: With this work, there's a lot of time invested up front with making the model. That's weeks of work right there. But after you've made those decisions, you can re-create that and produce it a lot more efficiently.

AB: And we both really do love the whole process. So we're still doing it all ourselves instead of skipping the parts we could outsource. That's honoring the tradition of craft.

JB: But now slip casting is becoming more of a popular thing in America, whereas in other countries... That couple that we met?... Where were they from? Norway or Sweden?

AB: Oh, yeah...

JB: That's what everyone does there; they all slip cast. And that's just because, I think, they're more design-oriented than America is.

AB: But now, people are coming back around to it because they've seen so much brown and round pottery.

JB: A lot of people call us now asking us for advice. We're still figuring it out! [laughs] But we're very open with sharing anything that we learn to help spread the knowledge. And I feel like that's how we're keeping pottery alive. By trying to figure out new ways with an old craft.