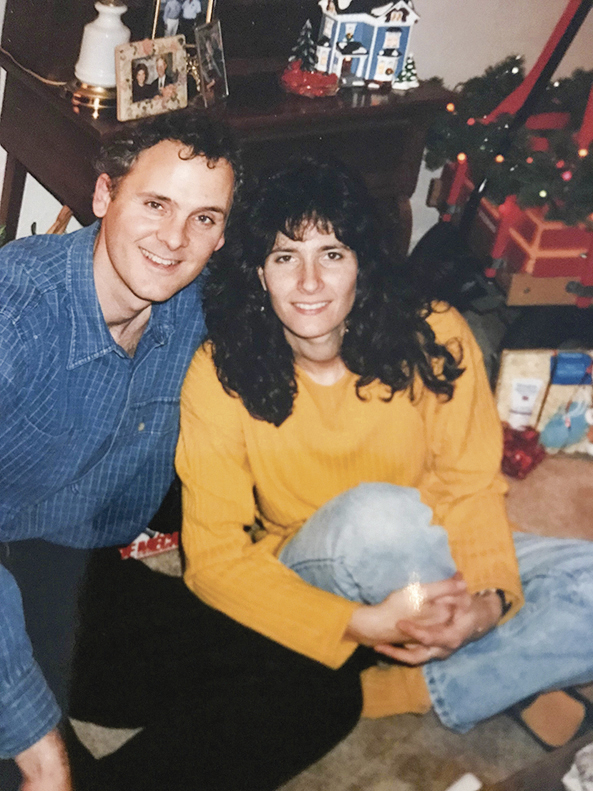

There's a 30-year-old photograph of my husband Daryl that I snapped at a convenience store somewhere west of Chattanooga. In it, he is putting gas in the car as snow builds up on the ground behind him, and smiling expectantly for the camera. We were headed to his parents' home an hour east of Memphis to spend our first Christmas together, and it was the happiest I'd ever seen him. It didn't matter that I was Jewish and that Christmas was about as important to me as the Chinese New Year is to an unborn baby. We were in love, and this was going to be the best holiday season ever.

And it was! At first. Three hours after taking the photograph, I entered a kitchen packed with enough hot food and homemade pastries to feed an auditorium of millennials, although there were only four of us. In the living room sat the largest assortment of wrapped gifts I'd ever seen outside of a television holiday special, stacked beneath a Christmas tree the size of a redwood. A hand-carved procession of robed men and farm animals snaked from one end of the coffee table to a manger on the other side of the magazines.

After a dinner that included copious amounts of roasted turkey and pecan pie, I sat in the warm glow of the tree lights, opening a seemingly endless assembly line of presents and setting them beside me on the sofa in a precarious tower. When all the gifts had been opened, a gigantic stocking shaped like a peppermint stick dropped into my lap. "From Santa!" announced the tag, and out poured 1-pound bags of M&M's and chocolate kisses, quart-size bottles of shampoo and conditioner (Daryl's mother was a beautician), an assortment of decorative writing pads and pens, fleecy slippers, jeweled barrettes, several pairs of knee socks, and a wallet containing a gift card to T.J.Maxx.

Post gift-frenzy, we all pitched in to corral the spent wrapping paper, bows and boxes into a giant garbage bag. Heaping plates of pecan pie made a second appearance and were eaten, and Daryl and his parents settled in to watch "It's a Wonderful Life." It was the most hedonistic fun I'd ever had outside of my 17th birthday party, when my parents were out of town and my older sister played chaperone until the daiquiris got the best of her and she threw up and passed out.

That Christmas far outshined the Chanukah of my youth, which unfolded like this: On night one of eight, we lit the first candle of the menorah, ate rational amounts of brisket and potato latkes, and then opened a few gifts. Although I wanted a horse more than anything, there was never a horse. The year my brother demanded "a minibike or nothing," he got nothing. For the remaining seven nights, we dutifully lit the menorah candles, but frankly, the glow was off. There were no more latkes, no gifts, no Chanukah specials to watch on TV and no days off from school.

Is it any wonder my thoughts were now throwing a party in honor of Christmas? "This is great!" I exclaimed in the privacy of my own head.

No sooner had the thought formed than a deep shame blossomed in the pit of my stomach. Making nice with Christmas was not the way of a good Jew. Had I not learned anything from my religious education? Wasn't participation in a Christmas tradition an affront to my parents, who, every December for seven years, marched themselves into my elementary school to fight for my right to sit out the Christmas pageant? Wasn't I thumbing my nose at the millions of Jews who suffered mightily for the right to practice Judaism without fear or persecution? Wasn't my merriment exactly what the rabbi of my conservative synagogue back in Atlanta, and my own father, had warned against when they sounded the siren of assimilation?

As it turns out, not exactly. What they feared was something more far-reaching and philosophically profound than Jews enjoying the spoils of another religion's holiday cheer - things like the gradual erasure of Jewish identity by modern society's seductive pull toward secularism, and apathy over the fate of Israel. Those were fears with teeth, true threats to my fellow Jews, unlike my greedy excitement at gifts under a tree and the ingestion of too much pie. But at 27, this was the kind of untested literalism that held me in its grip.

The longer I sat on the sofa, the worse I felt about everything, until the needle of my conscience made a startling shift from shame to self-abhorrence. I excused myself to the guest bedroom (taking the fleecy slippers with me), where I cried myself to sleep. Over the next two days I woke only for meals, retreating to the guest room to cry and sleep as soon as the meal was over. When at last it was time to leave to return to Chattanooga, I emerged from the bedroom with my suitcase, thanked Daryl's parents for the "lovely, really lovely" time, and rode home in steely and bewildered silence.

Had this been an isolated case of my ruining the holidays with misplaced religious fidelity, Daryl and I might laugh about it now. Instead, holiday celebrations unfolded in exactly this same way - minus the joyful photographic prologue - for well over a decade. When things finally shifted, when I was finally able to remain awake and tear-free at Christmas, we were in our mid-40s.

I wish I could say there was some big "aha!" moment that allowed me to see that my presence at my in-laws' home at Christmas did not threaten the progress of religious freedom across the globe. But the shift was gradual. It was true that, growing up, I'd been warned against assimilation. But it was also true that Jewishness "Shavin-style" was peppered with loopholes. We kept kosher, except for all those times my father snuck cereal on Passover and my mother ate mussels but only on the patio. We went to services at synagogue, but only twice a year. We drove and cooked and shopped on the Sabbath. We said the right prayers over the right candles at the right times, but you'd be hard-pressed to tease out of us a personal concept of God. And in these ways, we were not so different from many of our Jewish friends.

Fifteen or so years into my relationship with Daryl (and Christmas), I was finally able to ask myself what I was defending by weeping and sleeping at my in-laws' home during the holidays, especially as I committed no opposite but equally passionate energy to my own cultural commemorations and celebrations. It was the asking of that question that led to some deeper thought about how, exactly, I was connected to my Jewish identity, and in what way I wanted to honor that connection.

My family might fiddle with the finer points of kashrut (the kosher laws) and grapple with our personal concept of God, but this, I came to realize, did not negate my Jewishness. It lives in my bones, the accretion of centuries of ancestral vigilance and rehearsal. The real message of my tears and sleep at Christmas was not that I, with my fleecy slippers and T.J.Maxx gift card, was undoing what centuries of clashes over religious freedom had afforded the Jews. It was a whole lot less dramatic - and more personal - than that. In the shadow of the tree, and beside the hand-carved trek to the manger, I simply felt invisible.

That realization was yet another gift. My soul, busy having something of a near-death experience, rejoined my body in life. I stopped crying and sleeping at Christmas. I angled for less time at the in-laws, and Daryl and I spent more time thinking and talking about shared traditions. What would we create, we asked ourselves; who would come, and what would it look like?

It looks like this: Every fall, we make dinner for a big group of friends at our house to celebrate Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, and sound the shofar off the porch. Each spring, we host a big potluck Passover seder, complete with responsive readings, and during which our guests once spontaneously burst out singing a moving rendition of "Go Down Moses." (By that point it had been almost 10 years since I'd cried at a holiday, but this made me cry again - in the best way.) And we - along with my mother, Daryl's parents and aunt and uncle, a group of our closest friends, my brother and his wife and children, sometimes my cousins and sometimes a few neighbors - come together for a yearly blended Christmas/Chanukah party at our home.

There's enough food to feed an auditorium of millennials. Wine, too. A small pink Christmas tree and a silver menorah stand shoulder to shoulder on our kitchen counter. There are a few gifts. There is a lot of noise. And there's gratitude in abundance for this place of celebration - and inclusion - that it took us so long to figure out we needed.