Keri O'Neil is a heavy sleeper; few disturbances get her up and moving. But at 5 a.m. on Feb. 12, 2011 lying on the maroon carpet in Room 108 of the Key West Inn, all it took was a slight shake of the foot.

"Do you want to go some place really cool with me?" Grant Lockenbach asked.

"What?"

The room was still dark as eight other University of Florida students slept through the conversation.

They had come to LaFayette, Ga., to spend the day exploring caves.

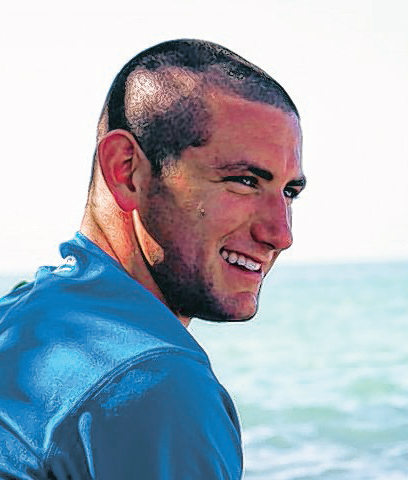

"Come on," said Lockenbach, who stood 6-feet tall, 175 pounds with a strong jaw and buzzed black hair. "I've been up for more than an hour. There's this really cool place I want to go.

Just come with me."He had checked into the hotel at 11:40 the night before, though nobody went to sleep until 3 a.m., when the second half of the group arrived from Gainesville. They'd been dating for less than a month, but O'Neil had already grown used to her boyfriend's impulsiveness.

When they couldn't decide on an appropriate time for their first date, he came to O'Neil's house and asked her to hop in his beat-up, green Volvo station wagon. He drove to Ben Hill Griffin Stadium, and they sat behind the end zone, just talking. It was a weeknight in January and Lockenbach had to get up at 5 the next morning for ROTC training. He didn't care. They talked for hours.

So, yes, on the morning of Feb. 12 she agreed to sneak out of the hotel. About 15 minutes later, she sat on a ridge overlooking LaFayette. Lockenbach didn't care about losing sleep. He wanted to watch the sun rise. Only problem was, neither of them knew which direction to look, or when the sun would actually come up. They sat. They talked. They waited. And, two hours later, shivering in the dim, 28-degree morning, they left.

As they drove down the hill, the sun peeked over the horizon. Lockenbach pulled a 10-point turn and gunned his car back up. "What were we thinking?" he asked, frustrated with his own impatience. "It's not like the sun just wasn't going to rise today."

Michael Pirie heard screams, but he didn't hear words. Nobody did.

It was 2 in the afternoon, and Pirie stood with eight others at the ledge of a 125-foot pit. The group was hoping for a fun weekend surveying Pigeon Mountain. But now, standing on that ledge, amid the darkness of Ellison's Cave, they were desperate to decipher Lockenbach's voice.

Each member of the group was part of Fellowship of Christian Athletes, and Lockenbach was the president. He was the most experienced caver - one of the only experienced cavers, in fact. A thrill seeker, Lockenbach had been caving for three years. During the 2010-2011 school year alone, he had gone on at least five trips, according to roommate Aaron McPhail. Two weeks earlier, Lockenbach led a group to Tumbling Rock Cave in Jackson County, Ala. Before that Lockenbach and his friends explored PettyJohns, one of the 59 other caves located inside Pigeon Mountain.

Lockenbach was a member of the university's ROTC, trained to parachute from planes and rappel out of helicopters.

He scaled his dorm as a freshman. Lockenbach was a member at a local rock climbing gym, where he once chatted with his mother on the phone while hanging upside down. On this particular Saturday afternoon, the rest of the students explored a separate part of Ellison's Cave while Lockenbach and Pirie rigged ropes at the Warm Up Pit. In the process, a black High Sierra backpack somehow fell 125 feet below them. The bag held ropes and other climbing gear, so Lockenbach went down to retrieve it.

Now, just minutes later, Pirie and the rest of the group listened intently. For whatever reason, Lockenbach's voice was not reaching them clearly. Perhaps his words were muffled as they bounced off the rocks. Or maybe he couldn't compete with the sound of the waterfall. Snow had fallen around the Chattanooga area three days earlier, and cold water ran through the cave toward the pits. During their exploration, the other eight students had, at times, been waist-deep. The group knew Lockenbach needed help, so three students sprinted down the mountain to call 911. They had brought a cellphone into the cave for emergencies, but it was in the bag at the bottom of the pit.

Pirie and the rest of the students who stayed in the cave heard bits of Lockenbach's screams. He yelled for Pirie. They tried to explain a rescue team was coming, tried to tell him to stay calm for just a little longer. In a half hour, they said, the rescue team will be here. But their voices weren't reaching him, and Lockenbach kept calling for Pirie, kept telling him he needed help.

The group needed a liaison, someone who could calm Lockenbach as they waited for the rescue team. A girl volunteered, but Pirie rebutted her.

"Can you pray for me?" he asked. "Because I have no idea what I'm doing."

He then strapped on a white helmet and descended. He didn't rappel, a woman in the group later remembered. He basically just fell down the pit.

"We're OK," Pirie yelled from somewhere below. "We're just cold."

Pirie, a first-year marketing major from Oviedo, Fla., played the bass in the 29-member UF drumline. He liked wake-boarding, snowboarding and doing flips off swing sets. He invented dances: stomp the rat, tip the hat, kick the cat.

On a previous trip to Gatlinburg, he became "Magic Mike" after surprising people with card tricks. As a senior at Lake Highland Prep the previous year, Pirie had been president of Project Magic, the Orlando chapter of David Copperfield's organization that performs in hospitals and low-income communities. He cut women into thirds and reunited them. He used metamorphosis to switch places with a friend padlocked inside a mailbag. He had mastered the teleportation box. But his specialty was sleight of hand. He was named Mr. Lake Highland Prep after turning one student's card into ash, rubbing it on both sides of his forearm and exposing a message reading, "The Ace of Spades."

At the ledge, Keri O'Neil prayed. God, save them. Comfort them.

Pigeon Mountain forms the right half of a V with Lookout Mountain, and the two fuse at the northwestern corner of Georgia. Pigeon occupies about 20,000 acres and stands about 2,300 feet above sea level. The mountain, along with a host of other tunnels, pits and holes in the sandstone have given the tri-state area a reputation around the country as a caving mecca. Every year, 10,000 cavers come to the mountain.

Between 1986 and 2008, there were reported incidents worldwide of 394 cavers falling, 162 being stranded or trapped, 169 being hit by falling rocks, 100 getting lost and 49 suffering from hypothermia. Seventy-five cavers died during that stretch, according to the National Speleological Society.

Nobody knows when people started investigating the intestines of Pigeon Mountain, but historians found ads more than a century old persuading readers to explore PettyJohns Cave. Ellison's is one of the most popular spots among experienced cavers looking for a challenge, most notably because of the Fantastic Pit and its 586-foot drop - the deepest caving pit in the continental United States.

The Crockford-Pigeon Mountain Wildlife Management Area is located off Georgia Highway 193, but even from LaFayette it can be difficult to find proper directions.

There are several cave entrances, and you won't find reassuring signs as you approach. Once inside, an inexperienced caver can easily get lost.

For Lockenbach, this was a proper sport, a sport untouched by manmade attraction. There are no real rules, only suggestions. The rocks are your boundaries. CavingV is not a sport in the sense of winning and losing.

There is no race to the top, no medal for exploring the deepest pits. And the danger, unlike in traditional sports, is always real.

Between 1986 and 2008, there were reported incidents worldwide of 394 cavers falling, 162 being stranded or trapped, 169 being hit by falling rocks, 100 getting lost and 49 suffering from hypothermia. Seventy-five cavers died during that stretch, according to the National Speleological Society.

But this trip was not about danger or, really, any type of discovery.

"We're OK. We're just cold," Pirie continued to shout up the pit to whoever could hear him.

It was 3:30. He had been in the pit for half an hour and he still did not know when the rescue team would arrive. He told Lockenbach they would soon be safe, and he kept yelling to Keri, letting her know they were hanging in. But the panic in Pirie's voice betrayed him.

"Grant!" he yelled. Pirie repeated the name twice more - Grant! Grant! - his voice growing louder, more desperate each time.

Keri asked Pirie if her boyfriend was OK, knowing the truth before the words escaped her mouth. Pirie did not lie, electing instead to misinterpret the question.

"I'm fine," he told her. "I'm fine."

She asked again. And, again, Pirie answered a different question.

By 3:45, Keri lost hope. She stopped asking questions. When the three-man Initial Response Task Force arrived at 3:58, she left with the two other women who had stayed in the cave. As she walked into the light, Keri cried, sure she would never see her boyfriend again.

The first members of the rescue team arrived in the gravel parking lot at the base of Pigeon Mountain at 3:11, about an hour after receiving the 911 call. Unlike with crimes or fires, caving emergencies demand a long response time.

CAVING TIPS

Know your limitations.Tell someone who is not going with you what you are doing and where.Wear layered synthetic clothing.Have at least two other sources of light aside from your headlamp.Check for recent rainfall and ask how rain affects the cave.

A rescue team isn't sitting together at a police station or a fire department, just waiting to spring into action when needed. Chuck Waters, the regional supervisor of the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, was at the mall when he received the call.

In all, the rescue team consisted of 34 members: five from the department of natural resources, six from Walker County Emergency Services and 23 volunteers. Among the volunteers were seven members of the National Cave Rescue Commission, a group of experienced cavers from all parts of the country. The commission happened to be holding a meeting in LaFayette that day.

Once members of the team had assembled, they still had to march one mile against 850 feet of elevation. The Initial Response Task Force started the hike at 3:20. They reached the Warm Up Pit about 40 minutes later, and Anmar Mirza rappelled to where Lockenbach and Pirie were suspended - about 80 feet down.

Neither man responded to Mirza's calls. Pirie was below Lockenbach, his head resting on his right shoulder and his helmet hanging by a string. Pirie's left arm was extended, a thick black rope wrapped around his wrist. That rope was entangled with another, this one thin and green and attached to a store-bought harness, typically made of nylon webbing with three loops: a big one at the top of your waist and two smaller ones below for each leg.

Lockenbach had tied his own harness with a rope, and unlike Pirie, he had a climbing system attached. To properly climb a rope long distances, you need ascender devices at least attached at two locations on your body, such as your waist and foot. Leaning on one of the ascenders, you pull yourself higher. Then, you switch, putting all weight on the ascender you just elevated.

On Lockenbach's harness, one ascender was clipped to his black rope, but a second one was just hanging, attached to nothing. When the rescue team found him, Lockenbach's mouth and nose were filled with water. His arms were stretched out, his face tilted toward the sky.

Nobody knows exactly what happened to Lockenbach during his descent. Some members of the rescue team think his rope was too short for the 125-foot pit. Others say the rope's length was fine, suggesting he was unable to maneuver once he became trapped in the waterfall.

Water running down the pit came from the melting snow - its temperature was in the high-30s or low-40s. Cavers are instructed to wear three layers of clothes in such conditions.

Lockenbach was wearing a blue Florida Gators T-shirt, Pirie a black long sleeve shirt and khaki shorts. When the rescue team found him, Lockenbach had been in the waterfall for more than two hours. Pirie had been in for about half as long.

It is possible that one or both of them had experienced cold shock response. With their bodies engulfed in water of that temperature, they could have hyperventilated for up to three minutes. Both men would have eventually recovered, however. At least until hypothermia set in. Your body temperature normally rests at 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit; hypothermia occurs when it dips below 95. In 40-degree water, it can take effect in 10-20 minutes, but Lockenbach and Pirie weren't fully submerged, likely delaying the process. Once hypothermia does take place, though, muscles grow weak and blood flows toward the core of your body, away from your extremities. You lose coordination.

The heart and the nervous system and other organs stop functioning correctly, and speech is slurred, and confusion sets in. Breathing becomes slow and shallow. Gradually, you fade. Organs soon fail; it just becomes a matter of which one stops first, which one becomes the culprit.

But well before any organ failed, well before the nearly ice-cold water overwhelmed Pirie and Lockenbach, they likely fell victim to Suspension Trauma. As you hang in a harness, blood begins to build up in your legs. If you can move around and shift your weight, the blood will continue to circulate.

But if you become tired and stop moving, your circulation slows. Your brain, realizing it is not receiving the proper blood flow, sends your body into shock. Your pulse increases. You breathe faster. You feel sick. You sweat. You shiver. You become anxious. Eventually, you faint.

When the rescue team found the bodies, they also found two lights shining: a headlamp on a nearby ledge and a Mini Maglite 40 feet below.

The week after the trip, Keri O'Neil would not eat unless someone placed food in front of her. The idea of standing up and walking across the room to her kitchen was exhausting.

She had good reason. Every night, almost every hour, on the hour, she woke up.

After her boyfriend woke her with a slight shake of the foot in Room 108 of the Key West Inn, Keri O'Neil became a light sleeper.

Area cavers say the accident at Ellison's Cave is a stark reminder of the subterranean dangers waiting for inexperienced adventurers.

"Caves can be very unforgiving places," says local caver Jeff Bartlett. "Even the simplest rescue operation takes many hours."

And Ellison's Cave can be particularly unforgiving. "It is not for beginners," says Amy Ward, a partner with which leads cave tours at Cloudland Canyon State Park. She says Ellison's should only be explored by experienced cavers because its pits require lots of rope work. "Vertical caving requires extraordinary skill; one mistake can mean the difference between life and death."

Ellison's Cave is 12 miles of twisting passages and plunges, including the 125-foot Warm-Up Pit where Lockenbach and Pirie died. The cave's 586-foot Fantastic Pit is thought to be the deepest pit in the continental United States. For reference, 586 feet is 19 feet shorter than Seattle's Space Needle and 31 feet taller than the Washington Monument. "This is not a place for new cavers," Bartlett says. "Even experienced cavers train extensively and visit several pits in the 200- to 300-foot range for practice before attempting Ellison's."

While Walker County Emergency Services responds to eight or 10 cave rescue calls a year, Fire Chief Randy Camp says most rope rescue calls are for people who are lost, have not reported back in by a specific time or have suffered relatively minor injuries due to falling. Although last year's accident was not the first fatality at Ellison's Cave, Camp says it may be the worst - partly because it was two people, and partly because of the young age of the two men. "This was definitely one of the worst cave accidents here in Walker County."

In addition to the pits, the Ellison's Cave is dangerous because of water, according to Marty Abercrombie, chairman of the Chattanooga Grotto. "You notice that there's no surface streams on the side of the mountains - that's because they're all underground," he says. "The whole mechanics of cave creation involves water."

Temperatures in the caves are normally around 55 degrees and the water can be even colder, Abercrombie explains. "Hypothermia is always one of those things in the back of my mind when caving," Ward says. "On trips where I know I will be almost constantly in water, I make sure to keep them short."

Abercrombie suggests wearing synthetic clothing because unlike cotton, it dries quickly and retains body heat. "Cotton kills is what we tell people," he says. "When it gets wet it just sucks the heat right out of you."

In the end, Bartlett says, pushing the limits ought to be saved for mountain biking or snowboarding. Caving, he explains, should be more about exploring the territory within your capabilities.

"If you're looking for an extreme sport, look elsewhere," he says.