While using the Blueway is easy, building, maintaining and growing the 50-mile water trail in the decade since it was created has been anything but simple. "Are you kidding me?" asked Philip Grymes of Outdoor Chattanooga, after rattling off a list of agencies, politicians and nonprofits involved. "That anything got done is incredible."

What started as little more than an interesting idea more than 10 years ago has become a nationally recognized recreation corridor that is now flowing down its feeder creeks and could soon jump its banks into new territory.

"That vision is starting to play out now," says Jeff Duncan, whom many credit as "the brains behind the Blueway." "The Tennessee River Blueway is a much bigger idea than just Chattanooga and the section through the Tennessee River Gorge. Hopefully in the next 10 years you'll be able to paddle from above Knoxville or maybe even Asheville, N.C., all the way to the river's confluence with the Ohio."

A Blue-what?

Simply put, blueways are designated water trails, usually designed for paddlers to camp along the waterway.

"The rivers and the streams are there," explains Jim Brown, executive director of the Tennessee River Gorge Trust. "You don't have to dig a trail, you just have to build the campsites." But that doesn't mean it's easy. The Blueway has taken years of work and a canoe-load of cash. The Lyndhurst Foundation alone has contributed about $550,000.

The idea started locally with Duncan, who in the early 2000s was working as head of the National Park Service's Southeastern Rivers Program. He started discussions with Brown about a river trail to give more people a new view of Chattanooga's revitalized downtown and pristine river gorge. Brown admits he did not really know what a blueway was when Duncan first brought it up, and says he was skeptical. "I kind of thought it was a passing fad," he recalls.

"It's just another piece among the puzzle of outdoor tourism for the Greater Chattanooga area." -Don Oliver

But he, like scores of conservationists before him, knew helping more people see the area he was trying to save would only help his cause. As a bonus, a blueway would encourage low-impact, human-powered boats, rather than carbon-emitting, wake-churning motorboats. Brown was sold and very soon, plenty of other key people were, too. Duncan and Brown began reaching out to other agencies like TVA, the U.S. Department of the Interior, Hamilton and Marion counties, the city of Chattanooga, Lyndhurst and private landowners.

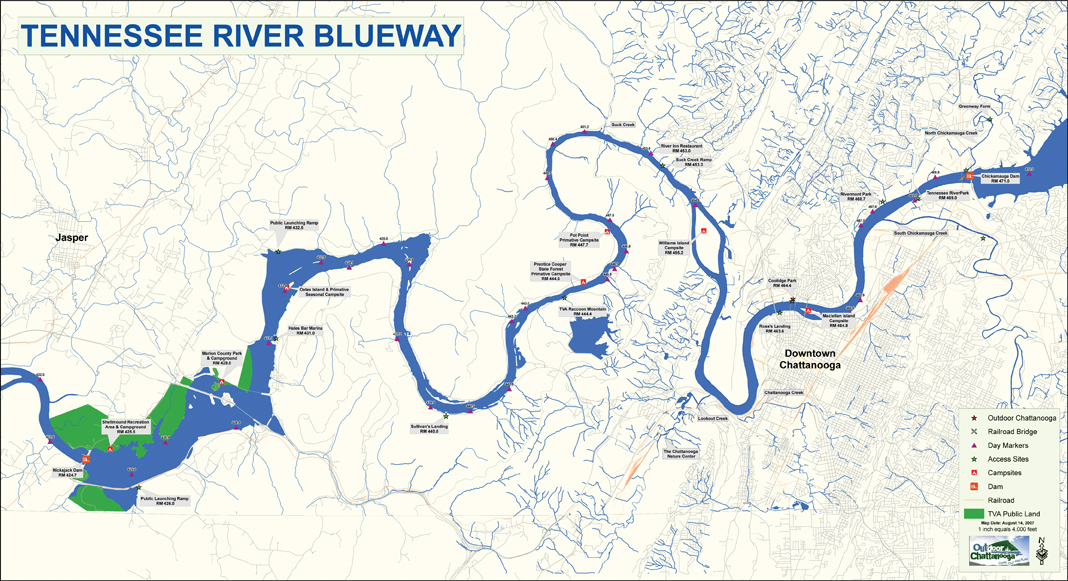

"An idea, if its time has come, is going to succeed," Brown says. "Its time had come. The cosmic tumblers were in place and the right people were in the right place and we got our Blueway." In May of 2002, then-Mayor Bob Corker, former Congressman Zach Wamp and National Park Service Director Fran Mainella officially recognized the stretch of the river between Chickamauga and Nickajack dams as the Tennessee River Blueway. The route was officially designated as a National Recreation Trail in 2006.

Blueway Today

"It's far beyond what I ever had thought it would be," Brown says.

Usage statistics for the Blueway don't exist, but Brown says the River Gorge Trust has issued "hundreds and hundreds" of permits for people wishing to camp at its Pot Point campsite. At Outdoor Chattanooga, Ruth Thompson says she receives about 40-50 calls each summer about the water trail. Some paddlers take a half-day trip, others spend several days exploring the trail's entire length. The great thing about the Blueway, Thompson explains, is that it can be many things to different people. "You can primitive camp on Maclellan Island or paddle to either side and go to a four-star restaurant," she says.

Few people know more about the Blueway's paddlers than Ray Gorrell, who runs River Canyon Adventures in the gorge. "There's a lot of people that come by," says Gorrell, whose campsite offers everything from kayak and SUP rentals to slacklining and disc golf. "It's expanding rapidly." He says the designation has clued more people into what he already knew. "They didn't know about it all being connected until we named it something," he explains. "They're putting it all together and it makes a lot more sense for people to see what I think is the most beautiful place east of the Mississippi."

But while Duncan is pleased to see his idea take off, it's not exactly going in the direction he expected. Ten years ago, he says, he would have predicted the trail to cross the dams and expand along the "thick blue line" of the main river. "The thin blue lines where it's coming off the tributaries are really where it's grown the most and that's what has surprised me the most," he says.

Feeder streams, like North and South Chickamauga creeks, have had established launch sites for years. Downstream of downtown, paddlers can hook a left into Lookout Creek and visit the Chattanooga Nature Center. "The feeder creeks give you a different perspective," says Jean Lomino, executive director at the Nature Center. "There's something really nice about being back in the woods." With support from Lyndhurst, the Nature Center opened its Paddler's Perch treehouse in 2009 to give Blueway travelers another lodging option.

The spread along the creeks doesn't appear to be stopping there. This summer the city of Chickamauga officially opened a launch on West Chickamauga Creek at Lee and Gordon's Mill. Plans call for interpretive signs and historical markers along the creek bank as it winds through the Chickamauga Battlefield. This month, officials in East Ridge and Fort Oglethorpe plan to open launch sites on West Chickamauga Creek at Camp Jordan and behind a cluster of restaurants on Battlefield Parkway. From there, paddlers can glide north to the Sterchi Farm put-in, a dock at the Riverwalk or out into the main body of the Tennessee. "It's just another piece among the puzzle of outdoor tourism for the Greater Chattanooga area," says Don Oliver, the Walker County attorney who is helping oversee the North Georgia launches.

Challenges Ahead

Despite the progress during the Blueway's first decade, Brown and Duncan say they can see the possibility for rough water ahead. There are important new steps to be taken, like finding more access between the Raccoon Mountain launch in the gorge and the Shellmound campground in Marion County. Others like Lyndhurst Executive Director Bruz Clark want to focus on developing and connecting to more activities around "nodes" like Camp Jordan, the Chickamauga Battlefield and downtown Chattanooga. Still others say promoting what's already there should be the primary focus.

"I think one of the missing pieces right now is management," Clark says. "There does need to be a coordinating body."

Duncan agrees. "It's part of the problem and it's also part of the beauty of it," he says. "Nobody owns it. And since nobody owns it, it's tough to get momentum behind it for maintenance and marketing."

Brown and others see long-distance land trails like the Appalachian Trail as a potential model. The Appalachian Trail Conservancy manages the overall picture of the trail, but localized organizations maintain particular segments of the footpath. "The challenges are solved the same way the Blueway was built - by the local groups," Brown says.

But despite this challenge, Duncan remains optimistic because of the support from all of the organizations and individuals involved. "Where it succeeded is that is has some momentum," he says. "It has a life of its own. In the first couple of years, some of us were doing CPR on it. The good news is that people now recognize the Tennessee River Blueway."