When David Gant saw the searing bright lights and heard the voices, he could only find one explanation.

He was hundreds of feet underground, 1,200 feet deep into a flooded cave. For nearly 18 hours he had been clinging to a stalactite gasping air from a tiny dry pocket in rock. His scuba tank was empty, his brain was foggy from a lack of oxygen and he thought he had just passed out briefly. His caving partners were probably in another similar air pocket or already dead.

Now, all of a sudden, blinding light poured into his dilated pupils and illuminated the tiny chamber. He heard someone shouting his name. Yes, it all made sense. The voices belonged to the angels that were about to take him to heaven. It was time to die.

"You guys are angels right?" he asked, bewildered.

"Dude," the frank voice behind the light told him. "We've been called a lot of things, but not angels."

Like most good Southern stories, this one begins with a big fish. One night 20 years ago in August of 1992, Gant and buddies Scott Clarke and Alex Miles dove into Nickajack Lake and swam under the fence blocking the mouth of Nickajack Cave.

Two-hundred-pound catfish were rumored to prowl the depths feeding on bat guano. On their first fishing trip, Gant had nicked a huge fish with his spear. "We were just hoping to get another shot on it," says Gant, a Bryant, Ala. native. Named after a nearby Cherokee village, Nickajack Cave in Marion County, Tenn., was flooded by the Tennessee River when TVA created Nickajak Lake in 1967. Since 1980 it has been off limits to humans because a huge colony of endangered gray bats has taken roost.

Johnny Cash had visited the cave before it was flooded with the intent of committing suicide. Cash's first marriage was falling apart and he was deeply in the grip of addiction. Country singer Gary Allan wrote a song about Cash's experience that says Cash could "feel the breath of death in Nickajack Cave."

After a few hours in the cave, Cash had a spiritual experience where he realized that life was worth living.

A few hours after Gant and his companions returned to the cave around 11 p.m. on Aug. 15, hoping to find the monster cat, Gant would know exactly what that "breath of death" felt like.

After searching for the fish without any luck, Gant checked his air gauge and signaled for Clarke and Miles to surface. They were getting low and it was about time to give up. But when they surfaced, expecting to find air in the large room at the mouth, all they found was water and rock.

Their search had taken them farther back into the cave than they'd planned. They dove and swam quickly toward where they thought the mouth was. But when they surfaced, they were met by only the cave ceiling with no room for increasingly important air.

Underwater visibility in the cave is better than other parts of the river, but frantic dive fins quickly stir up sediment. "As soon as you swim by, it stirs all of the silt up," Gant says. "Visibility can get to zero."

In a mad dash, they split. Gant swam furiously without knowing he was headed deeper into the cave. Clarke and Miles reached the entrance room and surfaced to gulp the night air. When Gant finally surfaced, he found air, but only the amount in a seven-inch dome of rock.

He was alone, in the dark, with a practically empty air tank and no clue which way was out. It was around 2 a.m. before Clarke and Miles were able to call 911. From there, the attempt to rescue Gant evolved into an operation on a scale that emergency workers had never seen before and are still talking about 20 years later.

A rescue dive team was called to find Gant, but emergency officials told the divers to prepare to search for a body more than a live victim. "It was being treated as a recovery not as a rescue," says Mark Caldwell, who in 1992 was a state emergency services coordinator based in Chattanooga. "The thought was that even if he had found an air pocket he would have been hypothermic and that would have killed him."

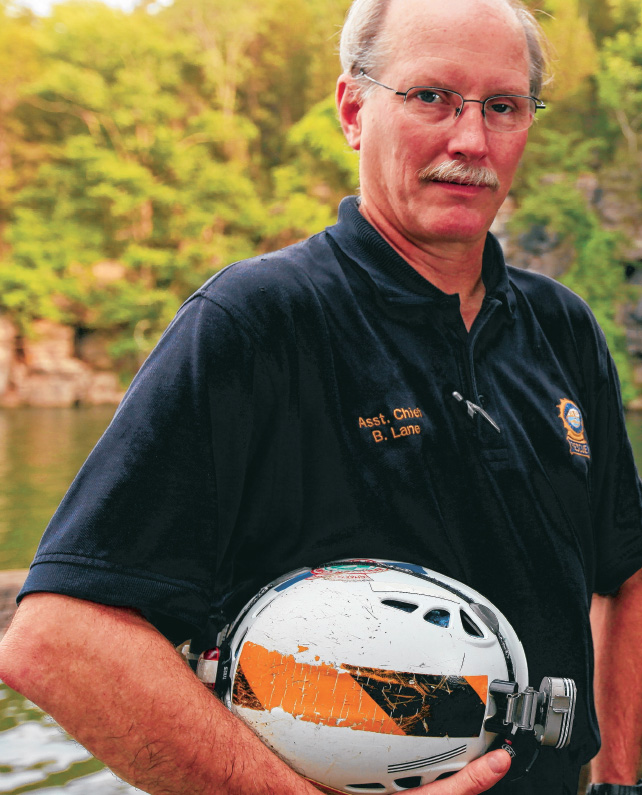

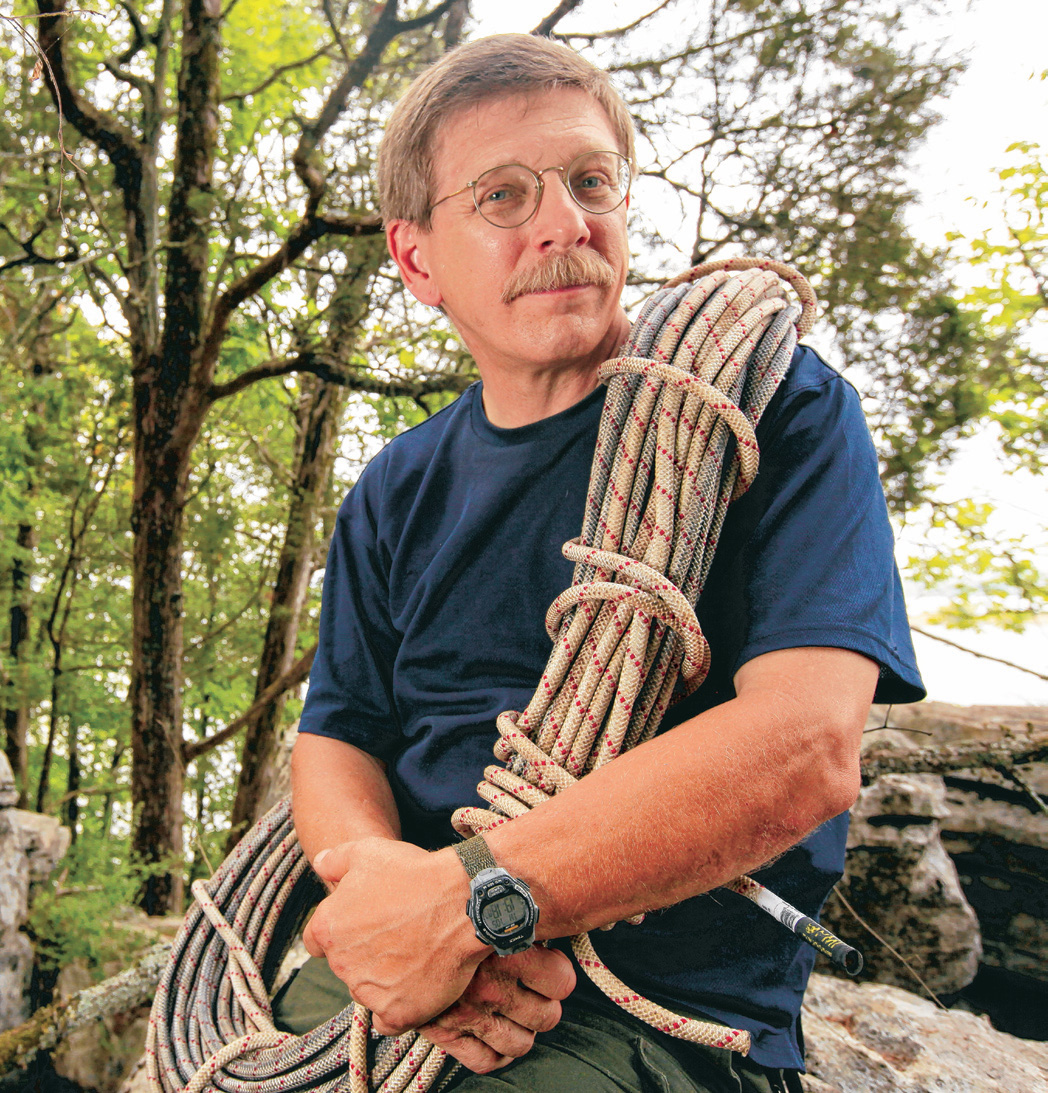

Divers headed into the cave but with limited knowledge of its twists and turns they didn't venture far. Caldwell, who was not involved in the operation at this point, says the divers were skilled, but not trained in cave diving. As dawn arrived, officials decided they needed maps of the cave system so they contacted Buddy Lane, a 20-year cave rescue veteran who lives in Chattanooga.

If cave rescuers had a Mount Rushmore, Lane's face would certainly be on it - maybe more than once. He not only helped create modern cave rescue but he continues to be the expert rescuers across the country call for advice.

That Sunday morning, Lane was able to meet TVA personnel and pull the large-scale map from the original cave survey. Looking at the map and the lake levels, Lane and rescuer Dennis Curry noticed several chambers that would likely be dry. "When we saw that, we actually had a little bit more hope for him," Lane says.

From there, Lane and Curry contacted Caldwell. Curry says Caldwell was one of the few people with the clout to shift the operation from recovery back to rescue. "They're calling me on a Sunday morning saying 'We need to take a second look at this, we think this guy may be alive,'" Caldwell recalls. "We were not going to treat this as a body recovery but a rescue until we got Gant out."

The map revealed that a drop in the lake level could give Gant a much better shot of survival because it would let air into the cave. It would also give rescuers access to much more of the cave without needing dive gear. But TVA had never dropped the lake for a rescue. Opening the dam would cost TVA tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars in electricity production. And that would be a lot of money wasted if Gant was already dead.

"This was a whole lot of government revenue," Caldwell says. "It wasn't going to look bad on anybody but me."

But he made the decision without hesitation and after a single phone call, the water began to drop - 14 inches in one hour. The drop was to the lowest level TVA allows because any less water would impede navigation on the river. Fourteen was a key number because there were 12-1/2 inches of water in Gant's air pocket. When the water dropped, the air rushed in with what he described as the sound of a train.

"He was out of air," Curry explains. "You have to realize that just as the water level came down he was about to pass out." His situation had steadily deteriorated for 15 hours, but things were finally turning. Soon after the fresh air hit him, he heard voices call his name. Then he saw the light. "At first David didn't believe Lane and Curry were real," Lane's original incident report states. "The first thought was he had died and was seeing things."

That's when he asked about angels and Curry cracked his sharp response. On his side of the light, Curry says he and Lane were nearly as surprised as Gant. "We were fully expecting to bump into his body," Curry adds.

The rescuers had ventured deeper into the cave than the divers. They didn't have air tanks but because the lake had dropped they were able to keep their noses above water as they swam. And while Lane and Curry were happy the gamble had paid off, their excitement was nothing compared to what happened out in the daylight. Curry says there had been a "deathwatch" for hours. Family and friends had comforted each other, preparing for the official bad news. When the boat came out with a living, breathing Gant, Curry remembers a "wave of exuberation" ripping through the crowd. "When he came out it was disbelief," Caldwell remembers. "So many people had resolved that he was deceased."

In all of his time in rescue, Curry says he doesn't know of another cave-diving rescue where the victim was found alive. "Usually, they don't find air," Lane explains. "There's no margin for error."

Realizing how close he was to death, has changed Gant. It's strengthened his faith in God and made him more sure of himself. "The guys at work the next day said 'You're different'" he says. "They just knew instantly."

He was interviewed by media organizations as far away as Japan and Australia. The story has been featured on the Discovery Channel and in Outside magazine. Everyone wanted to know the story of the miracle survivor.

"I've only seen a couple of men I know got a second chance and one of those is David Gant," says Curry. "A lot of things came together for Mr. Gant to see daylight."

Not the least of which was persistence by Lane and Curry. "I'm thankful," Gant says. "I'm so thankful that they did what they did and made everything happen."

Curry says they were just doing what he hoped others would have done for them. "I wouldn't want anyone giving up on me in that situation," he adds. "I don't want anybody to declare me dead until I'm cold and stiff in front of them."