Photo Gallery

How national nonprofits came to Tennessee to protect regions of unparalleled ecological importance

The land is the stage and the species are the actors. And we need to conserve the stage for all the actors, recognizing that as climate changes, species are going to move.

Deep in the heart of nearby Sherwood Forest, there lives a small, snake-coiled snail that cannot be found anywhere else in the world. The burnished brown-and-cream colored shell of the elusive "painted snake-coiled forest snail" (Anguispira picta) is unique - rarely found even within the confines of its only known home in the forests of Franklin County, Tennessee, where it relies on the specific pH balance of limestone-rich soil to survive.

Thanks to the efforts of a New York City nonprofit, among others, 4,062 acres of Sherwood Forest will be protected forever, in the hopes that nearby mining damage will not wipe out the remaining numbers of the rare, thumbnail-sized snail.

But the snail itself isn't the only reason for the assigned conservation status of the land, which was finalized this past winter following years of conversations. Sherwood is part of a broader focus on a new outlook of land preservation, one that seeks to answer the increasingly relevant question: As the climate changes, what spaces will remain resilient? And how can we make sure that these spaces and the creatures living within them are protected and able to thrive?

Those are the types of questions the Open Space Institute has traveled south to answer, while also seeking out conservation projects such as Sherwood to fund, says OSI Southeast Field Coordinator Joel Houser. The nonprofit has helped protect nearly 2.2 million acres across North America since 1974.

"Historically, conservation has often focused on one species like that," Houser says of the rare snail. "That's pretty neat, but it's not the only reason that land is important. The land is the stage and the species are the actors. And we need to conserve the stage for all the actors, recognizing that as climate changes, species are going to move."

Some species, such as the snake-coiled snail, are extremely particular about their environment. Searches in similar ecosystems for the snail have yielded zero documentation of it ever existing outside of Sherwood. For such species - and, thus, our overall ecosystem - having a path of viable land to migrate through to create a new home is the difference between life and death; between survival of the species and possible extinction due to changes in climate or habitat fragmentation.

"We see some species shifting even now," Houser says. "The challenge is to set them up in a way where they can move as quickly as the climate is forcing them to move. This is something that will go on forever. It's a long-term solution to give these species refuge in the future."

Many bird species, such as the burrowing owl (Athene cunicularia), are already increasing their ranges as their native homes decline due to the increase in that state's average temperature over the past 20 years. Due to changing climates, the owl is facing a loss of an estimated 77 percent of its breeding range across the South and Midwest over the next 50 to 60 years, according to the Audubon Society's recent climate report. Such temperature increases are expected to continue across most of the U.S., leading to lengthened droughts and heightened possibilities of flooding, rendering the fauna that many species rely on unable to exist and thrive as they once did.

Unlike conservation that focuses on a species or protecting spectacular views, in its excursion south, OSI is searching for ways to protect something much more fundamental: the soil.

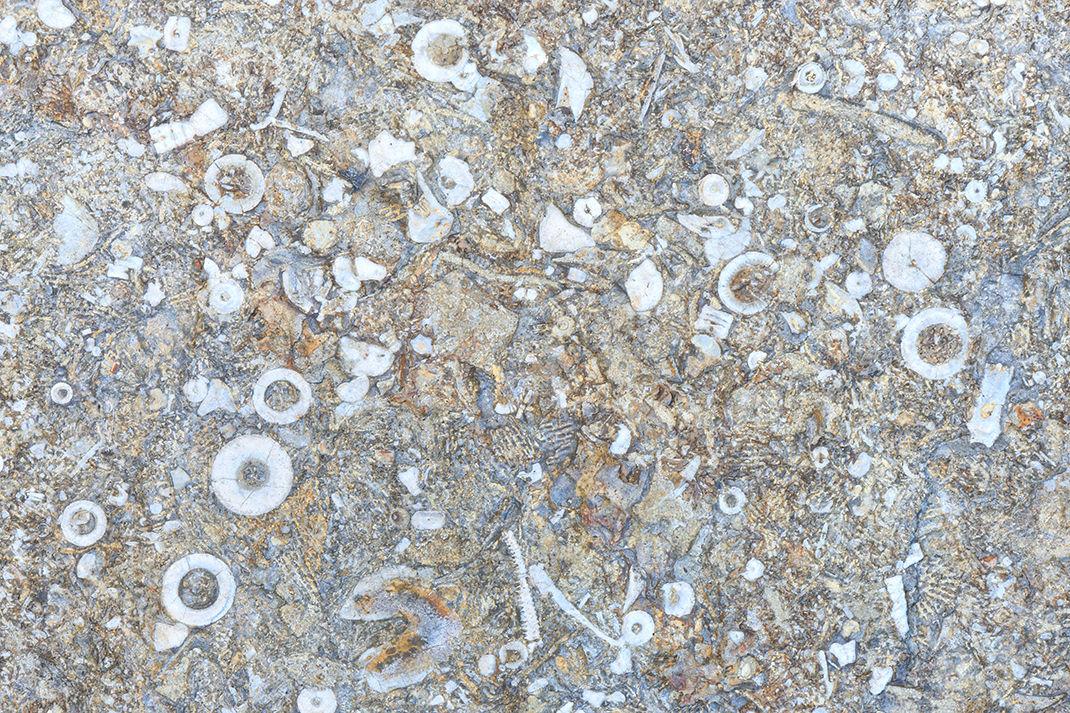

Due to a high prevalence of limestone coupled with a unique topography with complex landforms - a wide range of peaks and valleys, cave systems and more that can host a wide range of life and provide refuge that meets a variety of unique needs - the South Cumberland region is one of the most ecologically viable in the U.S., Houser says.

"In other words, the complex landforms and the geology of the area are crucial," Houser says. "We're really fortunate here, particularly along the escarpment of the plateau, that we have a lot of limestone geology. And that is by and large not protected. And there's over 500 species here in the Southeast that need that geology to exist. So protecting that and protecting micro-climates that are adjacent to each other are really the focus of our efforts."

Thanks to the ideal pH balance of the soil for a variety of life - from the alkalined limestone coves and flat areas to the more acidic sandstone soils at the tops of peaks - an incredible array of life is able to exist in these South Cumberland-area ecosystems, Houser says.

In order for his New York City nonprofit to protect ecologically important dirt in Tennessee, partnerships with local conservancy groups have been and continue to be paramount, Houser says.

The Tennessee Nature Conservancy's initial study on the resilience of areas across the state in 2005 helped inspire OSI's trek to Tennessee, but the relationship didn't end there. The conservancy has played a role in several of OSI's eight South Cumberland preservation projects, including Sherwood. Together, the projects form a collection of more than 10,000 acres that can serve as an oasis for animals needing to migrate as their current habitats become no longer able to sustain them.

The current concerns extend beyond the birds whose forest habitats may see a decline in other parts of the state and country. Creatures such as the Northern flying squirrel (Glaucomys sabrinus), American red squirrel (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus), the endemic junaluska salamander (Eurycea junaluska) and the pygmy salamander (Desmognathus wrighti) thrive in higher elevations that offer cooler but still humid temperatures, something which characterizes much of Tennessee's more mountainous forests.Fortunately, the eastern two-thirds of Middle and East Tennessee are covered in underlying limestone, says TNC Director of Protection Gabby Lynch. The healthy soil and resultant plant life that limestone facilitates is ideal for creating corridors or safe havens to allow wildlife to survive both natural and man-made changes elsewhere.

Ideal areas for the corridors were outlined in TNC's Tennessee Wildlife Action Plan, which was updated in 2015 in conjunction with the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency.

"It looks at the records of rare and threatened endangered plants and animals, forest corridors. Any and all biological diversity information is cooked into that action plan," Lynch says.

But due to its ideal soil and topography, this critically important soil and surrounding landscape are also in the largest amount of danger for building, mining - as was the case for Sherwood - or farming. "It's highly developable, it's usually flat, so it's one of the most at-risk geologies. And Tennessee has a lot of it," Houser says, further explaining that the low pH balance of the peaks gives way to large expansions of flat, calcareous soil-filled lands below, which "give rise to perfect farmland."

The dream is for the corridors to span far beyond the Southern Cumberland region of Tennessee and tips of Alabama and Georgia. OSI officials envision protected lands, identified for their ability to thrive, connecting along the Appalachian Trail and running all the way up to Maine, where other key areas have been highlighted for similar resiliency traits.

To achieve success in such a broad-scaled endeavor requires complex partnerships and cooperation. The owners of the land must be sought out and negotiated with. Purchase deals can take years, not to mention the enormous amounts of funding that must be solidified in order to allow for such purchases. OSI's national recognition helps in this regard, connecting local conservation groups with different focuses in order to secure funding from large-scale environmental nonprofits, such as the Virginia-based Conservation Fund, which provided more than $8 million in front-end money to aid with the quick purchase of any South Cumberland lands as they became available.

"We use our capital to get it out of the private landowner's hands, and then our capital gets replenished when [we sell the land] to the state," says the fund's Conservation Acquisition Representative Ralph Knoll. "We can provide quick funding that these other organizations might not otherwise be able to raise in enough time when a landowner says 'I want to sell it to you, I like you, but I want the money now.'"

Of OSI's six successful Southern Cumberland projects, the Conservation Fund assisted with four, either giving funding outright or loaning it, such as in the case of the now-popular climbing destination Denny Cove.To successfully secure the Cove, OSI connected the Southeastern Climbers Coalition with the Conservation Fund. SEC spent four years working to secure the 686-acre parcel touted for its vertical slabs, overhangs and sheer number of routes with unique climbing opportunities, says SEC Executive Director Cody Roney, but it was the fund that loaned the more than $1 million asking price.

For Roney and the rest of the climbing community, the idyllic spot located about 30 minutes north of Chattanooga was a land of untapped opportunity. The unique topography and geology of the area also made it interesting for OSI, due to the mineral-rich dirt existing underneath the rock formations and the climate resiliency the dirt fosters.

After SEC purchased the land, the group retained temporary ownership to build a trail to the climbing destinations, then entrusted it to the state for conservation.

"This was a million-dollar-plus purchase, and that was not something we ever imagined [we could do] but everything worked out really smoothly. And having those partnerships now is invaluable to us," Roney says. "We all had different interests in the property, but it came together."

As the Earth's temperature continues to rise at rates of .29 to .46 degrees Fahrenheit per decade - more than double the rate of temperature increases the previous century saw each decade, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency - such partnerships between organizations with different interests and lenses for conservation will only become more necessary.

Places such as the South Cumberland region, which have largely resisted climate changes and have been identified as future refuges, must be preserved, Houser says.

"It's a hot spot not just in the Southeast, but in the country."