Differences

* In American Sign Language, communication is done through hand shapes, direction and motion of the hands, body language and facial expressions. Known as ASL, the language has grammar, sentence structure and word order that is unique to it. * Lip readers watch the movements of a speaker's mouth and face to understand what the speaker is saying. About 40 percent of the sounds in English can be read from the lips. But some words can't be read. For example, "bop," "mop" and "pop" look exactly alike when spoken. Even so, a good speech reader might be able to catch only four or five words in a 12-word sentence. Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention To Learn If you are interested in lip-reading classes, contact David Harrison at 624-1669, dmharrison1@juno.com or letmypeoplehear@yahoo.com.

David Harrison kept what he thought was a shameful secret for years after he graduated college.

His wife guessed his secret while they were still dating, but Harrison would stare at himself in the mirror every day, talking to his reflection, trying to figure out how to keep his embarrassing skeleton hidden in the closet.

He kept the secret during the five years he led a ministry on a Cree Indian reservation in Canada then pastored a Kansas church, then the 20 years he traveled across America entertaining children as a Christian magician, got married and fathered three children before settling in Chattanooga in 1995.

The secret? Harrison is legally deaf.

He tried to conceal it for most of his life by becoming a skilled lip reader and learning to speak out loud. It may seem incredible that anyone considers deafness embarrassing, much less shameful, but Harrison, 77, was born in an era when deafness was not well understood by educators or even the medical community.

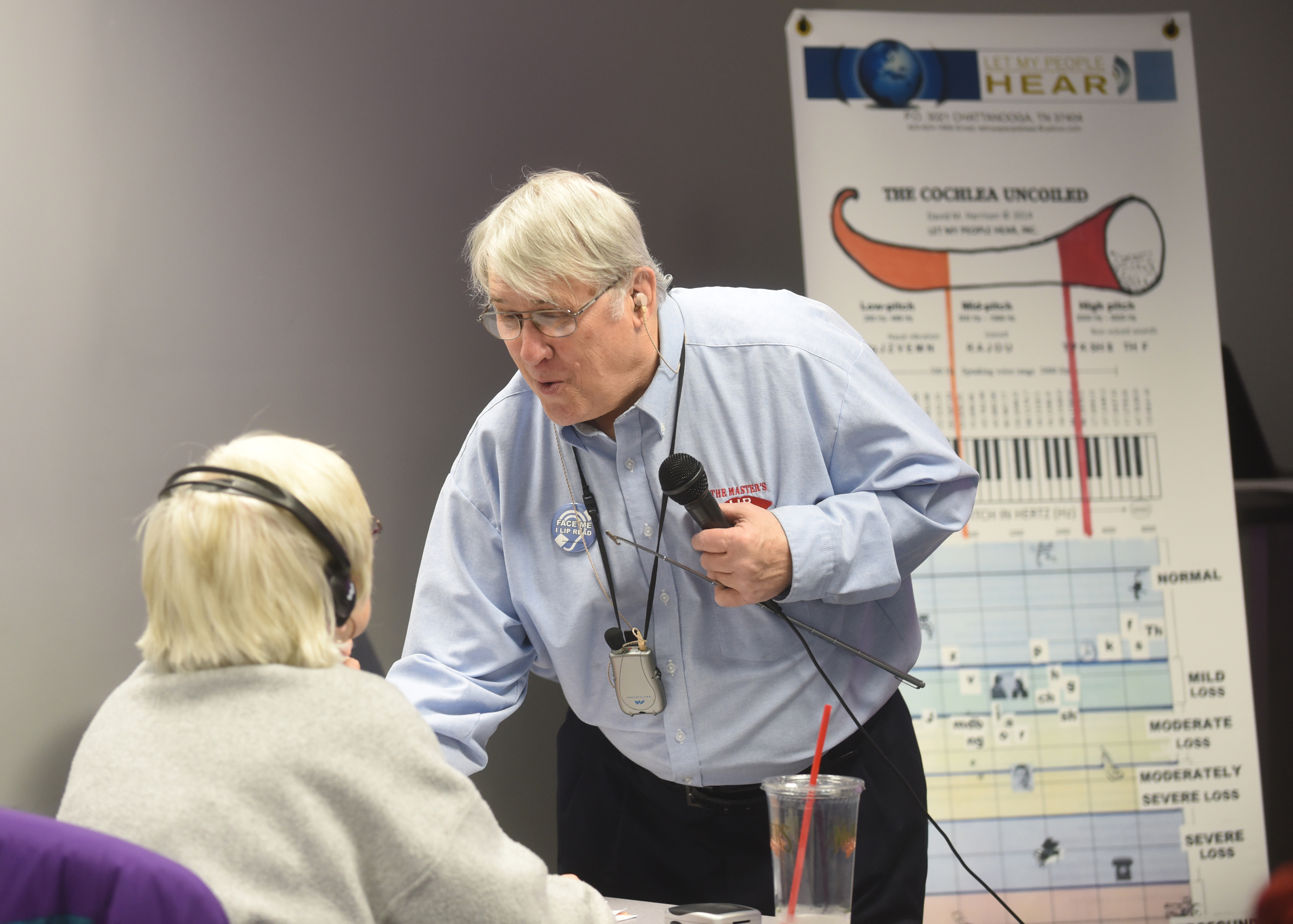

Born hearing disabled -- meaning he could hear some sounds but not clear speech -- he now teaches lip reading to other hearing-disabled individuals and tries to give them the emotional support and confidence to see that deafness does not prevent them from being fully involved with the hearing world. He believes he may be the only teacher in the state to offer in-person rather than online lip-reading classes.

"Sign language is fine, but not many hearing people know sign language," Harrison tells a class of hearing-impaired students who are taking his lip-reading class at Chattanooga State Community College. "But most pastors, college professors, bosses and co-workers don't know sign language if they can hear. Lip reading can help you communicate professionally and socially in the hearing world."

Harrison speaks rapidly and without stumbling over words. He enunciates carefully so reading his lips is fairly easy for those who have some lip-reading experience, according to students in one of his classes. A blurring of the vowels is the only hint that he may not hear as well as anyone else.

But lip reading can be controversial. Many deaf activists argue that the hearing disabled should use their energy to learn American Sign Language instead of lip reading because sign language has the range, precision and nuances of any spoken languages. Those who promote lip reading -- also known as oralism -- say it's the best way to integrate deaf people into society as a whole, but some in the sign-language camp says it's more important for the deaf to integrate into their own culture.

The late Roy Holcomb, who supervised a pioneering elementary school curriculum for the deaf in California in the 1960s, estimated that lip readers grasp only about 50 percent of what is said. He noted that few people enunciate clearly, so many words require similar lip movements making them hard to differentiate.

The attitude of some sign-language proponents angers Harrison, who believes the hearing impaired and deaf are often shoved into sign language because deaf activists believe lip reading is a limited and demeaning form of communication.

Harrison concedes that lip readers normally grasp around 50 percent of what is actually said and rely on context for the rest.

Partnership for Families, Children and Adults client services manager Sharon Bryant says research from Gallaudet University (a historic school for the deaf) found the comprehension rate a mere 30 percent for lip reading.

"I am deaf myself," Bryant says by email. "American Sign Language is the most dominant language among deaf people. The reason for this is because we rely heavily on visual language. ... If a hearing person becomes deaf later in life, they try lip reading. If [there's] no success, then they try ASL Its easier for hearing people to do lip reading than signing."

Laura Brown, who took Harrison's lip-reading class, is hearing impaired yet she served in the military and worked in a pregnancy care center, raised a family and became a published author. She understands why Harrison tried to hide his hearing disability.

"When I first started to lose my hearing years ago, I tried to pretend I heard what people were saying to me," she recalls. "My husband would try to reassure me. But it's frightening. I was in denial even during nine years of wearing hearing aids because they amplify sound but do very little for clarity.

"Lip reading is a very helpful skill. A lot of the words do look the same if the speaker isn't enunciating, but you can use context. And now I tell people I am hearing impaired. Most people are nice. They will remember to look at me so I can see their lips."

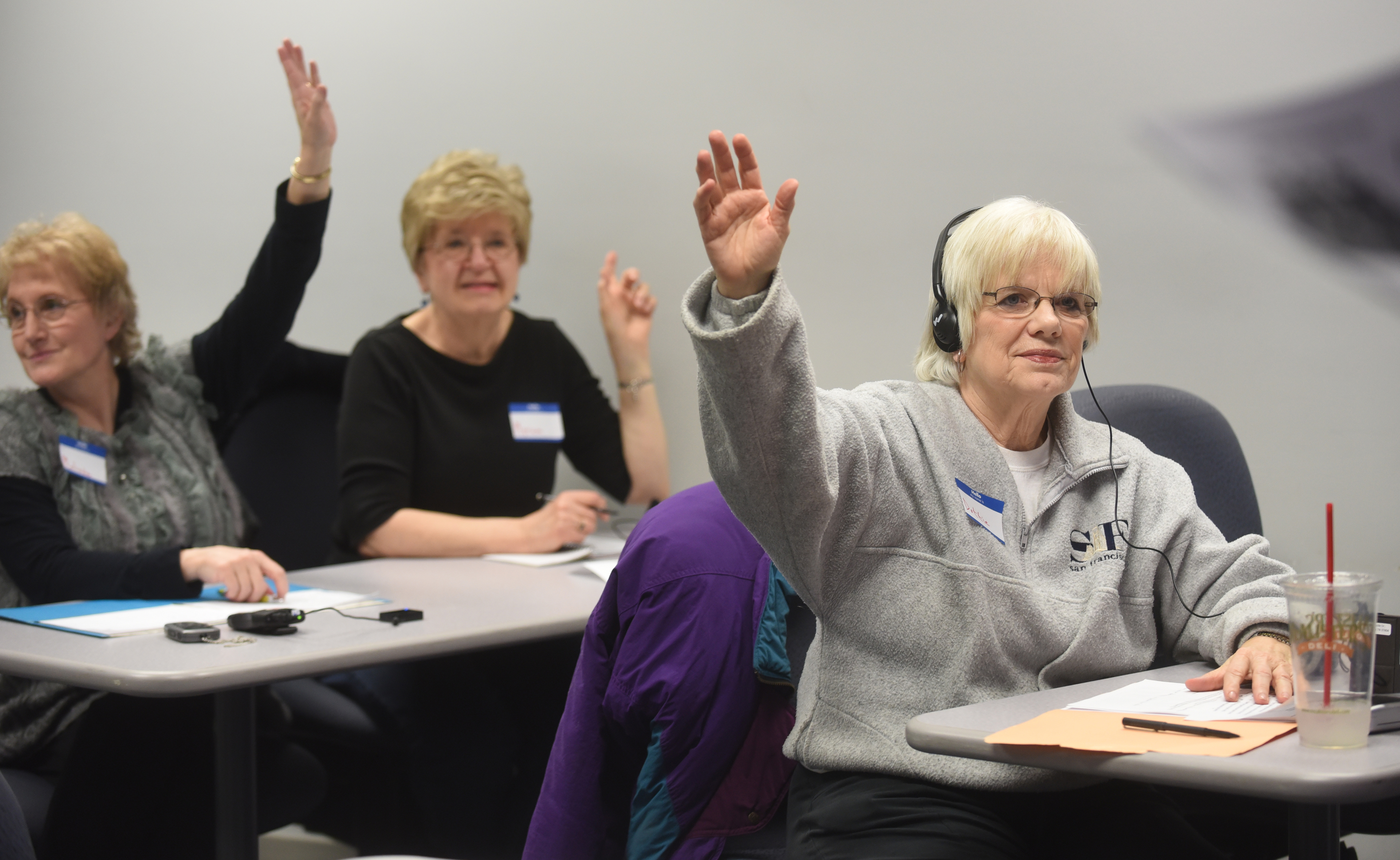

The students in Harrison's class enjoyed the lessons and camaraderie so much, they revived the Hear Now Cafe, a monthly meeting where they share emotional support, coffee and cookies. Covenant Baptist Church at 1640 N. Joiner Road offers them meeting space.

Harrison hopes to find a church that will offer him a permanent space where he can teach lip reading; in exchange, he says he'll install equipment that makes whatever words are spoken in sanctuaries and meeting rooms accessible to the hearing impaired.

AUDIO ADJUSTMENTS

Attending elementary school in the 1950s, Harrison could seldom hear what was being said, so he would miss verbal directions and had to ask teachers to repeat words. When he spoke, he was not always able to enunciate perfectly. Teachers decided this was evidence of what they called "mental retardation" and put him in a class with mentally disabled children.

He was in that class for five years before someone figured out he was simply hard of hearing. But those five years had an impact; he realized he would have to rely on himself to survive in the hearing world and decided to focus on lip reading rather than sign language.

Although a skilled lip reader, he still practices by watching himself speak words in front of a mirror, studying the shapes his own lips make when he says certain words. Even a two-syllable word like "hello" involves five micro movements of the mouth, he explains.

He wears a hearing aid while teaching his classes although, when he was a little boy in 1948, he rejected a hearing aid that he won at the state fair.

"Chrome-plated vacuum tubes and a lot of wires. I never could adjust to it," he recalls. "There's a misconception that you put an aid in your ear and boom! -- you hear. But hearing aids have problems with feedback, static and amplifying background noise."

Growing up, he learned to position himself directly in front of teachers so he could watch their lips. But in his five years as a pastor on a Cree reservation, he hit some snags because tribal members tend to look down while talking.

In his junior year of college, he married Cathy, a nurse who can hear. She would interpret for him when needed.

When Baptists transferred him to a Kansas church in 1970, he had to try a different tack to hide his hearing impairment.

"I tended to dominate conversations, so I wouldn't have to listen and figure out what was being said," he remembers wryly.

In his next job, Harrison spent 20 years traveling across North America as a magician for Vacation Bible Schools and church youth groups. His three children and wife helped by playing music and assisting with props. His favorite trick was sawing pastors in half.

After attending a conference in the early 1990s in Chattanooga, the Harrisons fell in love with the city and moved here in 1995. While sitting in a local pew, Harrison realized that churches in this area isolated the hearing impaired.

"I couldn't read the pastor's lips when he walked around preaching, and I'd see people in the congregation, thousands of dollars of hearing devices in their ears, who couldn't hear what was happening," he says.

In 2006, David and Cathy completed academic coursework to be certified as "support specialists" by the American Academy for Hearing Loss (now known as the Hearing Loss Association of America) and decided to launch a ministry to the deaf called Let My People Hear. Harrison offers to donate his services to any church that will let him make it deaf-friendly.

"I have most of the equipment; an FM receiver system can be used in a sanctuary and T-coil loops, which plug into some hearing aids, so people can hear the FM transmission," he says.

He used the technology in his Chattanooga State class in February, and his students seemed happy with it.

All of Harrison's children were born hearing and have shown him clearly that a hearing impairment never needs to be embarrassing. Harrison says when his grandkids are chatting with him, their parents often remind them: "Stand in front of Grandpa so he can see you when you talk. You know he can't hear you!"

When Harrison tells that story, he laughs wholeheartedly.

Contact Lynda Edwards at ledwards@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6391.