If you go

If you want your child (or yourself) to be tested at LearningRx to see if you have any issues with cognitive abilities, call 423-305-1599. The reduced-price testing -- $49 instead of $199 -- runs Thursday through Saturday. To learn more about LearningRx and its methods, go to learningrx.com.

Chase Foster is trying to concentrate, but the noise around him is borderline chaos.

"Whoo-hoo! Gimme a high five!" someone says nearby. "Yay! Good job!" another person exclaims. Electronic metronomes click loudly on numerous tables, making the room sound like it's full of crickets.

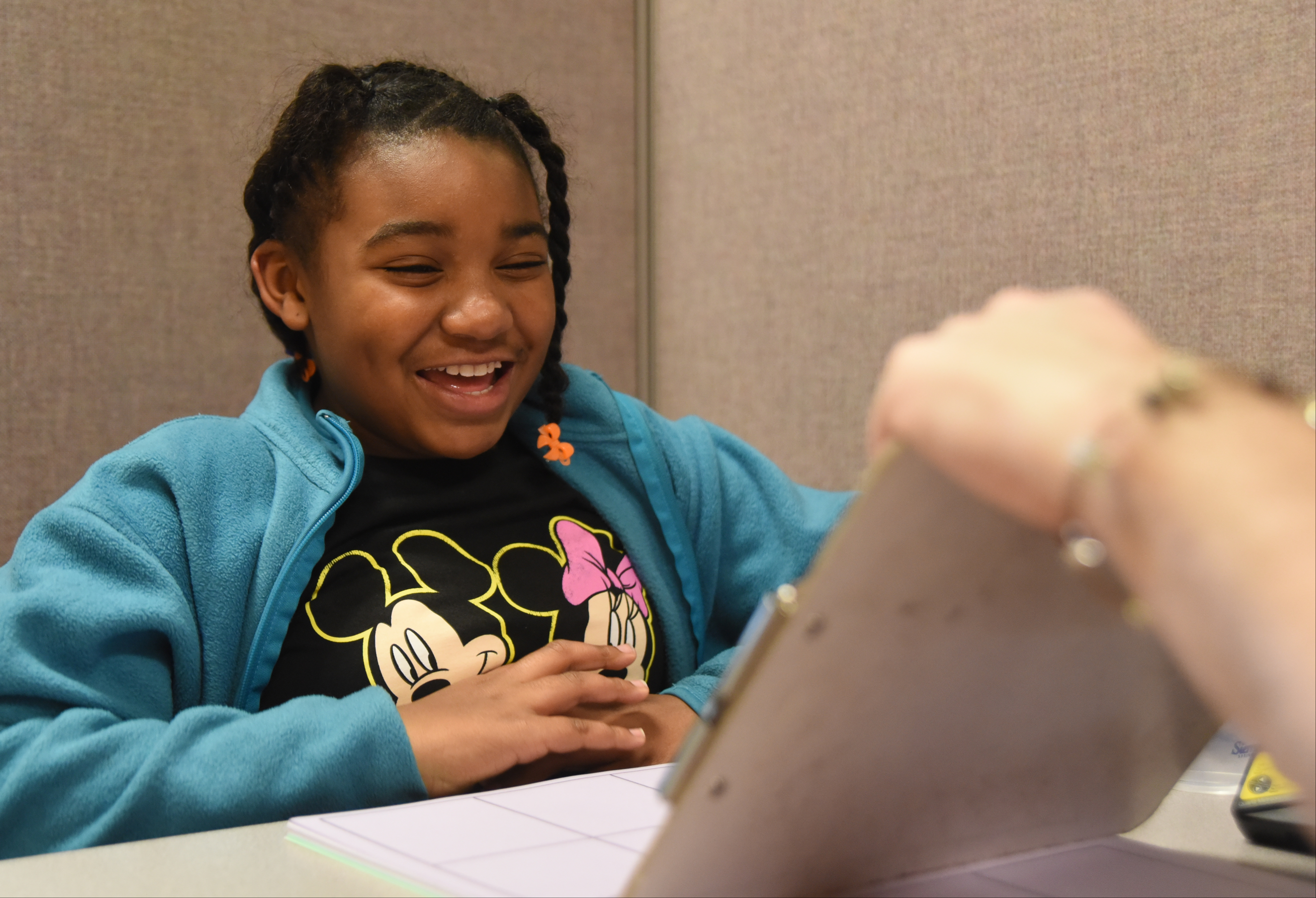

"OK," says Kasie Jackson, sitting across a little table from Chase, "now take a 90-degree turn and go four steps."

Staring intently at a "Where's Waldo" puzzle, Chase does as instructed, only to have Jackson immediately give another instruction: Turn this way, walk this many steps; then turn this way and walk this far. He follows each command without a problem.

"Alright!" Jackson says "Five out of five! High five!" She and Chase slap hands as a smile splits his face. Then they move onto another puzzle because this is serious business.

At LearningRx out by Hamilton Place mall, puzzles and games are more than just fun-time activities -- although fun is part of the process. The students -- and some adults -- are trying to train their brains to do better on seven categories ranging from memory to brain processing speed to attention span.

"It's not just doing a puzzle, it's working a math problem, it's reading effectively and fluently," says Michelle Hecker Davis, executive editor at LearningRx, a national chain. "The brain is what processes and dictates how quickly and easily you learn."

For instance, jigsaw puzzles address visual processing and sustained attention, while a Rubik's Cube taps logic and reasoning and visual processing. Tic-tac-toe speeds up your thinking.

Even the noise is part of the process, forcing students to fully concentrate, Davis says.

For Chase, "Where's Waldo" has been improving his listening comprehension, his ability to visualize, his logic and his working memory.

Cognitive abilities

* Working memory * Brain processing speed * Long-term memory * Visual processing * Auditory processing * Logic and reason * Attention Source: LearningRx

"I'm not real good at comprehension, like when someone reads a story or something to me," says the 14-year-old from Ocoee Middle School in Bradley County. But he gives a quick "Yeah!" when asked whether the puzzles at LearningRx have helped.

It's no surprise then that National Puzzle Day, which lands on Thursday, is a top-notch marketing chance for a business like LearningRx. So from Thursday through Saturday, it's offering brain skills testing at 75 percent off its usual price, dropping from $199 to $49. And before you ask, no, puzzles aren't part of the testing; they use the Woodcock Johnson test, the same one that Hamilton County Schools uses to judge students' abilities.

Sure, the reduced price is a way to get people to come to LearningRx and maybe sign up for longer-term training, but Davis is a fervent believer that these tests can help youngsters and adults discover whether they have any cognitive issues. And she's also certain -- and has the graphs and charts and studies to back up her claim -- that the puzzles and games and other methods at LearningRx can improve those problems.

"The skills that you use to work a puzzle are the ones that we train at our facility," she says.

Science seems to back up the idea of puzzles helping with brain function.

Research at the University of Chicago found that children who play with puzzles between ages 2 and 4 develop better spatial skills, the ability to understand and manipulate shapes and spaces. Such talents allow you to use a map in an unfamiliar place, learn to navigate through a new building, even comb your hair while looking in a mirror. According to the study, such skills also help predict whether kids will be able to easily master courses in science, technology, engineering and mathematics, or STEM.

As for older folks, a study published last year in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society said a series of brain exercises over several weeks helped them retain improved reasoning skills and brain-processing speed for 10 years after the course ended.

Called the Advanced Cognitive Training for Independent and Vital Elderly study, or ACTIVE, the federally funded trial of 3,000 older adults by Johns Hopkins University was the largest study ever done on cognitive training in the elderly. Average age of the participants was 74 when they started the training, which involved 10 to 12 sessions of 60 to 75 minutes. Ten years after the training ended, researchers found that adults who had it did better on cognitive tests than those who didn't.

The results "suggest that we should continue to pursue cognitive training as an intervention that might help maintain the mental abilities of older people," National Institute of Aging Director Dr. Richard J. Hodes said in a statement.

However, other research says just doing puzzles isn't an effective method for staving off memory loss in aging adults. According to a 2013 study from the University of Texas in Dallas, the key is to learn new skills. Doing crossword puzzles over and over simply makes you good at doing crossword puzzles, the study says, but demanding activities that you've never tried before -- say digital photography, learning a new language -- can make a difference in retaining memory abilities.

The study used 221 adults, ages 60 to 90, who were told to engage in different activities for 15 hours a week over three months. Some took on new tasks such as photography and quilting, others were given everyday tasks such as doing word puzzles or listening to classical music. At the end of the study, those given new skills to learn showed improved memories; the others did not.

For kids, the ages from birth to 7 years old are crucial for developing the cognitive skills they'll carry throughout their lives, Davis says. But issues such as ADHD, dyslexia and autism can make it difficult if not impossible for them to master all these skills.

For aging adults, it's a matter of "keeping the mind limber because our brains can change at any time in life."

"Some adults come to us and say, 'I'm having trouble recalling a specific memory,'" she says.

At Creative Discovery Museum, which focuses on kids, they don't get into all the cubes, flash cards and what-not like LearningRx. They like puzzles. Plain ol' puzzles everyone put together one piece at a time as a child.

Murky beginnings

Truth is, the origin of National Puzzle Day, always on Jan. 29, is a puzzle itself. Some say game companies started it in 1995 as a marketing tool, but others say its origins are actually a -- ahem -- puzzle. Whoever started it, Puzzle Day now shows up all over the Internet in the days leading up to it, including mentions on Pinterest, eHow and kidsactivities.net.

"I'm all about the puzzles," says Jenette Dean, early childhood manager at the museum. "Puzzles are excellent help in developing the brain. They help with visual/spatial concepts if the children have to turn the shapes and fit them in."

Puzzles "are really good" for developing hand-eye coordination and muscular motor skills, she says, while working as a group teaches them the social skills of cooperation and getting along with others. And moving beyond those simple concepts, puzzles with letters on them help teach the alphabet, while the shapes -- triangle, square, rectangle, etc. -- often are a child's earliest lesson in geometry.

You don't have to convince Chase or his mother, Trina, who brings him to LearningRx three days a week, then does training homework with him on three more days. Chase has been doing the work since June and his mother says the difference in him is obvious.

Before, it was a chore to give him a household chore, she says. "The info goes in but it doesn't go anywhere," she says, so the chore wouldn't get done without telling him over and over. And woe be unto you if you gave him something that required multiple steps, she says. "He could only handle a task if it was one sentence," she says.

Now, a single instruction usually gets him going and he can handle a multiple-step process without losing his way, she says. "I've also noticed that he's better at comprehension, at recall and his grammar and speech are better," she says.

As Chase and his mother leave through the front door of LearningRx, the din in the room continues, then suddenly escalates. Loudly.

"I love it! I love it!" one of the trainers exclaims. "Very good! That's the best you've ever done! High fives! You know what? Let's ring the bell."

The sound of a clanging bell reverberates throughout the room.

"When someone has been working on something for a really long time and they finally get it, we ring the bell," Davis says with a smile.

Contact Shawn Ryan at sryan@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6327.