DANGEROUS ADVICE

Some well-known weather sayings are so wrong they're potentially deadly. * Lightning never strikes the same place twice. Absolutely, positively false. As an example, lightning strikes the Empire State Building in New York about 25 times per year. Lightning tends to strike the highest object in an area, and it is attracted to metal. * Tornadoes never attack mountains. The thought is that mountains break up the weather fronts that create tornadoes, but tornadoes have been sighted in the Appalachians, the Rockies and the Sierra Nevadas. They're rare in mountains because air that high is cool, and tornadoes usually need warm, unstable air to form. But in 1987, an F4 tornado roared for 24 miles across the Rockies in Wyoming at heights from 8,500 to 10,000 feet. In the Appalachians, a mile-wide tornado hit Roanoke, Va., in April 1974. * Tornadoes never hit cities. Nashville would beg to differ. A tornado roared through the city's downtown on April 16, 1998). Other cities hit by tornadoes include Miami, Salt Lake City, Birmingham, Oklahoma City, Houston and Fort Worth. As NOAA points out, tornadoes are usually 5 to 10 miles tall; even a 1,000-foot building (92 stories) cannot deflect something that big.

The past few weeks have been rough 'n' tumble for regional weather forecasters.

A few days before Feb. 17, they were predicting 3 to 5 inches of snow in the Chattanooga area, but by Feb. 16 had changed that to freezing rain and ice. People rushed to the stores to grab food; schools closed before the morning even arrived. When Feb. 17 dawned, there was nothing, no ice, no snow.

A little over a week later, they were warning of up to 6 inches of snow on Feb. 26. People rushed to the stores; schools closed before the morning arrived. The snow started falling on the evening of Feb. 25 and, by the next morning, sure enough, there were about six inches of snow coating most of the metro area, deeper in the higher elevations.

Even with all the computers, satellites and hi-tech gear now employed by meteorologists, they'll readily admit that predicting the weather can be tricky. Winds suddenly change direction; warm and cold fronts get stubborn, refusing to move when computer models say they're supposed to. Temperatures rise and fall from the ground to the upper atmosphere, changing water droplets from rain to sleet to snow to freezing rain as they tumble from the sky.

So if they have trouble getting their forecasts spot on even with all their electronic help, what about turning to old-fashioned methods? What about weather folklore? You know, sayings from the Farmers Almanac or the ones your grandmother said with a serious nod of her head or your grandfather came out with while standing in the fields, looking up at the sky.

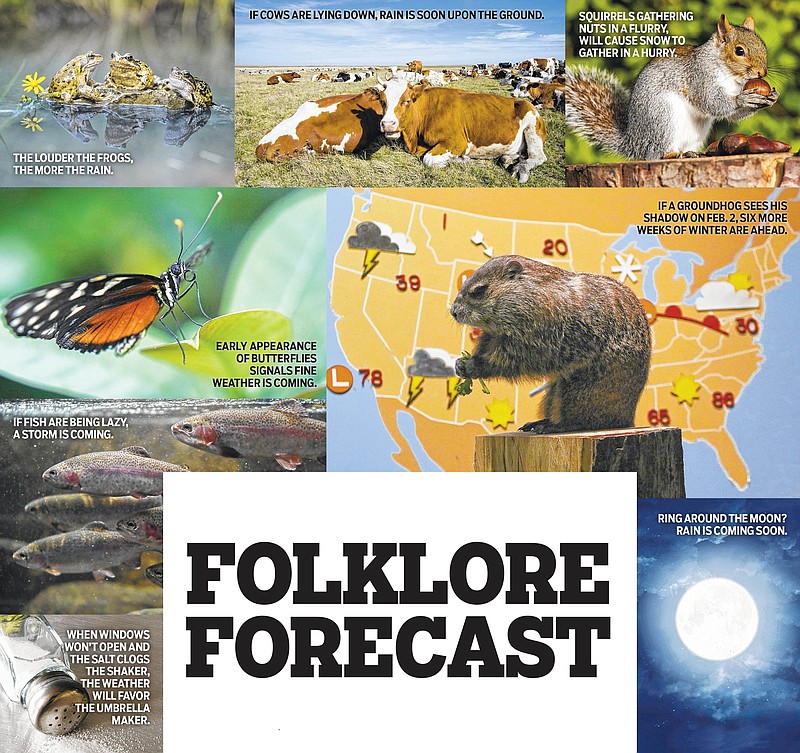

"Ring around the moon? Rain is coming soon."

"For every fog in August, comes a snowfall in winter."

"Squirrels gathering nuts in a flurry, will cause snow to gather in a hurry."

"If cows are lying down, rain is soon upon the ground."

Chief Meteorologist Paul Barys at Chattanooga's WCRB Channel 3 is a weather folklore skeptic. Before coming here, he worked as a meteorologist in Cleveland, Ohio, where an annual festival honors the woolly worm's alleged weather predicting powers. The darker the coat of the worm (an Isabella tiger moth, actually), the colder the winter is supposed to be. Barys says it's an example of people conflating coincidence into a forecast. One thing does not necessarily lead to the other, he says.

"Ohio folks were always coming up to me saying they saw a lot of fat bears in the fall so we were in for a hard winter," Barys says. "Here's what fat bears mean - berry season was good and they ate well."

Still, there is scientific reality behind some of the sayings, he acknowledges, for instance, watching some animals' behavior.

"In the short term of two or three days, animals do seem able to sense changes in air pressure and fronts moving in," Barys says. "Cattle tend to huddle together before a storm, which is dumb because one lightning bolt can take out a whole group. Cattle are dumb. Their ability to sense a front moving in is instinctive.

"There are some bits of folklore that have been proven true, but folklore will not save your life or tell you which way a tornado is coming."

Big predictor

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration provides the data often used by meteorologists and other weather forecasters. Qi S. Hu and Kari Skaggs, from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, did perhaps the most detailed study of NOAA's forecasts back in 2009.

They examined the six- to 10-day forecasts from NOAA's Climate Prediction Center for the Lower 48 in the U.S., the forecast, "identified by farmers and extension agents as the most useful forecast for nearly all farming decisions during the growing season," the duo wrote.

They calculated that NOAA has a 40 percent accuracy rate overall for its six-day forecasts. In comparison, the world's most famous groundhog, Punxsutawney Phil, has a 50 percent success rate predicting winter's end over the past 20 years, according to NOAA's National Climactic Data Center.

Perhaps the new weather supercomputer being built by IBM this year for NOAA will boost its accuracy rate. The agency is spending $44.5 million for a system of leading-edge predictive devices. About $25 million of the investment was provided through the Disaster Relief Appropriations Act of 2013, a boon bestowed by Congress in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy.

Historical predictions

Attempts to accurately predict the weather have been around since the B.C. era. The Babylonians began trying it in about 640 B.C., according to NASA, while the Chinese developed a weather-oriented calendar by 300 B.C. Even Aristotle wrote about the weather and his theories on how to predict it.

While weather instruments were produced beginning in the Middle Ages, prediction was still mostly a matter of watching the sky and feeling the wind until the invention of the telegraph in 1835 allowed weather reports to be tabulated from across a wide area, then sent hither and yon in a matter of seconds.

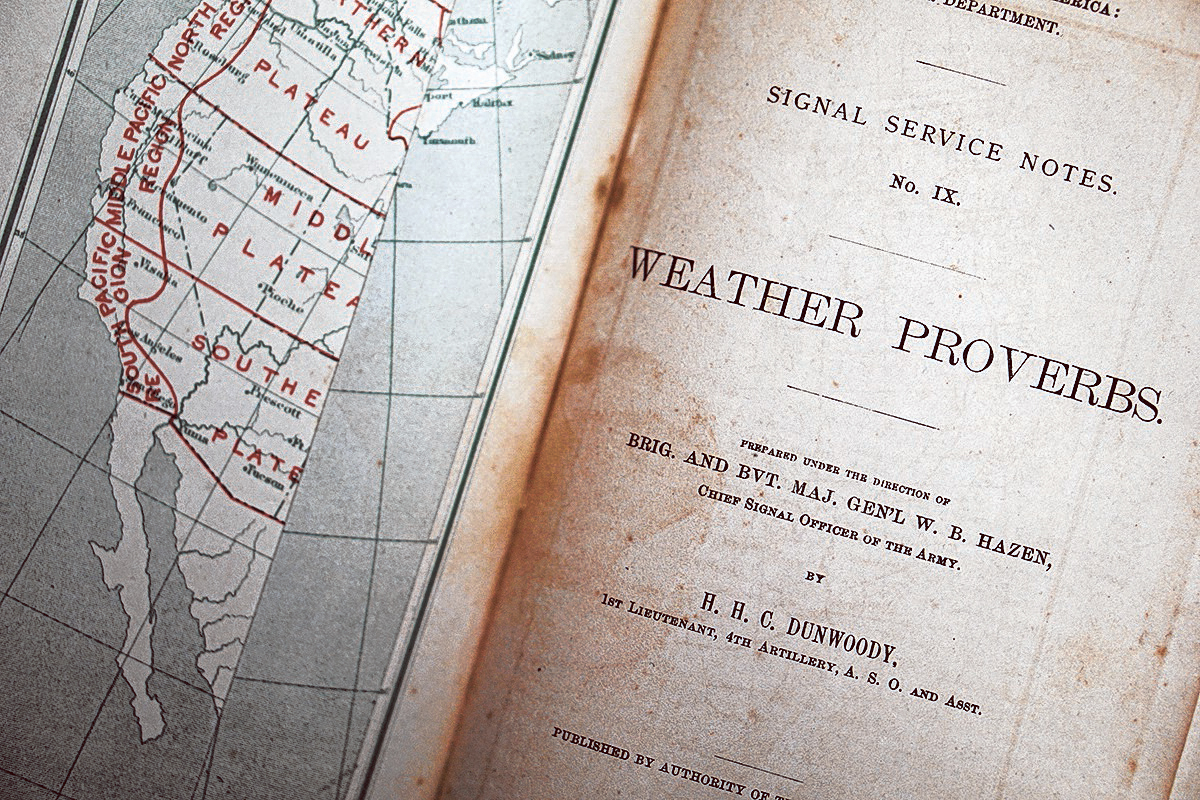

A major weather-predicting project was launched by U.S. Secretary of War Robert Todd Lincoln in 1883, an era when cataclysmic thunderstorms could destroy more Navy warships than any battle. He wanted soldiers across America to collect and report "weather proverbs and prognostics used throughout the country by all classes and races of people including Indians, Negroes and all foreigners." Lincoln thought perhaps the ancient weather proverbs might prove more reliable predictors than what weathermen were currently using: thermometers, wind vanes, humidity gauges and weather balloons.

Brig. Major Gen. W.B. Hazen, chief signal officer of the Army, collected hundreds of proverbs his men reported and divided them into categories: sun, moon, stars and meteors, rainbows, mist and fog, dew, clouds, frost, snow, rain, thunder and lightning, animals, birds, fish, insects, flowers and trees. At the time, the Signal Corps provided vital intelligence about troop movements, the terrain ahead and impending weather. The often whimsical and poetic weather proverbs Hazen collected were published under the boring title "Signal Service Notes No. IX Weather Proverbs."

In the book, some proverbs verge on the lyrical: "If the moon shows her silver shield, be not afraid to reap your field"; "Marry the rain to the wind and all will be calm"; and "Low over the grass the swallows wing and how sharp the crickets sing; rain is coming."

Animal intelligence

Tennessee Aquarium Communications Manager Thom Benson has a copy of "Signal Services Notes IX" in his personal library. He has never tried to validate the weather maxims by observing the creatures in the aquarium because "all our fish and birds are in safe indoor environments, they're buffered from the outdoor weather."

But some weather proverbs in the book have been proven true, and Benson has collected some that involve what he jokingly refers to as the "Aquarium Animal Storm Track Team." For instance:

* If fish are being lazy, a storm is coming. Fish become inactive just before thundershowers. As the atmospheric pressure gradually builds during the storm they swim deeper to hunker down. They stay down lower for some time after the storm passes, too.

* The louder the frogs, the more the rain. A single frog won't croak louder, but clouds that are especially rain-bloated prompt more frogs to call out, meaning more noise. The proverb comes from the Zuni Indians in New Mexico, whose powers of weather observation were so respected, Hazen included an entire academic paper about their proverbs in his 1883 book.

* Early appearance of butterflies signals fine weather is coming. Imagine a warm day during winter, sunshine glittering on melting frost. Suddenly, a cluster of bright butterflies swirls around you. You think it's a fleeting warm spell; the butterflies know it actually means the bitter cold will soon be gone.

NOAA approved

There also are some weather proverbs that are so accurate, NOAA considers them to be helpful predictors.

* When windows won't open and the salt clogs the shaker, the weather will favor the umbrella maker. Moisture in the air makes windows stick and salt clump, indicating a higher chance of rain.

* Winter wind from the South carries snow in its mouth; winter wind from the West carries rain at best. This one is especially true for Southeast Tennessee, North Georgia and Northeast Alabama. Wind coming up from the Gulf Coast is warm and wet; big snowstorms occur when it slams into cold fronts coming down from Canada and across the Western Plains. Without that joining of wet South and cold West, snow is unlikely.

* Red sky at night, sailors' delight. This famous maxim is true along most of America's coastal waters and the Great Lakes, but not so much on the Gulf Coast, where summer pop-up storms are common.

Aches and pains predict rain

The National Weather Service was predicting a wintry mix of sleet, rain and snow on Thursday, but East Ridge's Teresa Ketterer Norton said she knew it wouldn't amount to much.

"My back makes me a human barometer," says Norton. "I've had six operations on my back. When a front is moving in with snow or heavy rain, there is a strange pressure on my back. It's not piercing. It isn't really pain. It's just a very strange, unsettling weight that I feel along my back."

Norton's back was feeling fine on Wednesday, no aches. On Thursday,

The idea of body parts predicting weather is not all that loony. Back in 1883, the Army Signal Corp - the weathermen for the military - proudly boasted that its state-of-the-art forecasting tools came from natural sponges, whalebone, catgut, human hair and animal skin, materials that expand and contract with rising and falling humidity and air pressure.

New proverbs?

So will the climate change now taking place around the globe bring forth a whole new set of weather proverbs?

"The quick answer is probably yes, but no one knows," replies James White, a biochemistry and paleoclimate dynamics expert, which means he studies climate change over the history of the Earth.

He lived in Knoxville long before he became a Colorado University professor and director of Boulder's prestigious Environmental Studies Program. He examines how climate change affects weather forecasting and, as an Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research fellow, he's had a chance to observe climate change globally.

"I think it's safe to say that changing climate will make long-term predictions harder for the foreseeable future (including) seasonal predictions of use to farmers," White says. "The usual five-day forecasts will be less affected as they start with existing conditions which can be well-observed.

"What is changing now is that we are seeing bigger rainfalls, which follows from a warmer atmosphere which can hold more water. That might mean that flooding will be harder to predict well and also might mean that flooding will be more common," White adds.

"I think the fine folks who monitor the Tennessee River and manage its flow will probably be among those who are challenged."

Contact Lynda Edwards at ledwards@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6327.