If You Go

* What: "IndiVisible: African-Native American Lives in the Americas" exhibit. * Where: Museum Center at Five Points, 200 E. Inman St., Cleveland, Tenn. * When: 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Tuesdays-Fridays, 10 a.m.-3 p.m. Saturdays, through July 3. * Admission: $5 adults, $4 seniors and students, free for children under 5. * For more information: 423-339-5745.

Two old-fashioned, wooden auditorium chairs might be questionable additions to a Smithsonian Institution exhibition, but in the case of "IndiVisible: African-Native American Lives in the Americas," the folding chairs are silent reminders of the struggle for acceptance by the two featured minorities, especially those who intermarried between those races.

"The chairs are balcony seats from the Princess Theatre in downtown Cleveland, where blacks and American Indians had to sit prior to civil rights and desegregation," explains Joy Veenstra, the Museum Center at Five Points' curator of education.

"IndiVisible" is the Smithsonian Institute's traveling exhibit that reveals unique information about the little-known history of people with dual African-American and Native American ancestry. It is a walkthrough display of 15 large panels that discuss the cultural integration of these blended marriages and the ancestors caught between preserving their individual heritage and embracing both cultures.

Veenstra believes the exhibit is an obvious fit for the Cleveland museum due to the area's Cherokee history.

"There is a lot of Cherokee influence, Cherokee history here in Bradley County," she says. "A lot of people hold onto their Cherokee heritage and are proud of it.

"This exhibit highlights a culture and heritage that has never been studied or identified until the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian did this research into the African-American and Native American culture -- specifically families who are blended."

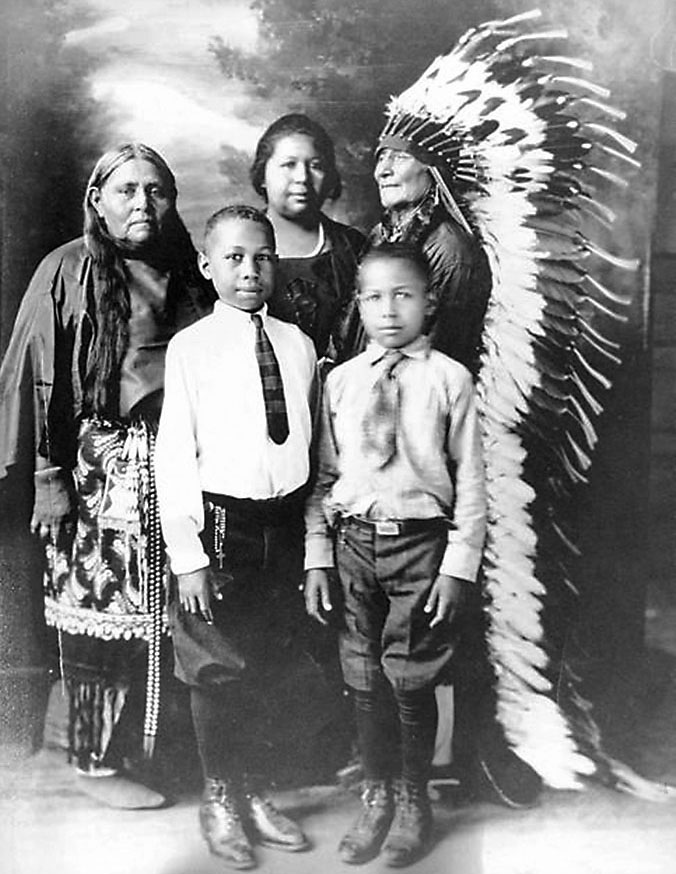

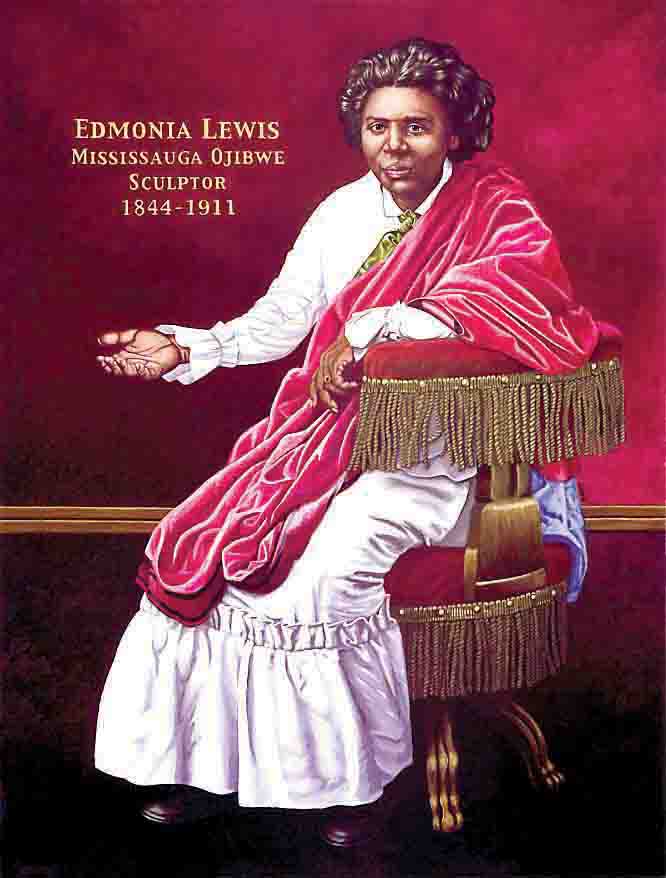

In addition to numerous large panels on which texts and images of documents are displayed, there are photographs of interracial families past and present. Rock legend Jimi Hendrix is among the portraits; the musician often spoke of his Cherokee grandmother. Black jazz trumpeter Adolphus "Doc" Cheatham claimed Cherokee and Choctaw ancestors.

Of particular interest to Veenstra is the section about Cherokee Freedmen. In the 1830s, blacks owned by Cherokees accompanied them on the Trail of Tears to Oklahoma. By 1861, there were an estimated 4,000 black slaves living among the Cherokee, according to the Smithsonian exhibit.

After the Civil War, the tribe signed a treaty granting former slaves, or freedmen, "all the rights of native Cherokees." But in the early 1980s, the citizenship rule was amended to require "direct descent from an ancestor listed as Cherokee by blood on the Dawes Rolls," the U.S. government's census of the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek and Seminole tribes in the 1890s and early 1900s. As a result, nearly 3,000 descendants of Cherokee freedmen were excluded from membership. To this day, the Cherokee claim "the right to define tribal membership lies at the core of self-governance," while descendants of freedmen claim they will not give up their rights to citizenship.

The Museum Center staff has pulled items from its collections to enhance the IndiVisible panels' information. In addition to the auditorium chairs, the objects include a handwritten poem from an African slave written in 1863, an 1849 bill of sale for an African girl and an 1858 bill of sale for a boy.

A third section of the exhibit asks visitors to examine what makes them unique: heritage, physical identity, genetic traits?

"The topic of African-Native Americans is one that touches a great number of individuals through family histories, tribal histories and personal identities," said National Museum of the American Indian Director Kevin Gover in a news release. Gover is a Pawnee.

"The exhibition acknowledges the strength and resilience we recognize in one another today," Gover said in the release.

Contact Susan Pierce at spierce@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6284.