Brad Sundstrom can memorize:

* Two decks of cards in 5 minutes then name each one in order.

* Five hundred numbers then recite them in random order 15 minutes later.

* Names and faces of dozens of strangers in 15 minutes.

* Numbers spoken by another person at a rate of one per second then immediately recite them back.

* A 50-line, brand-new poem.

* The details - from engine parts to decorative elements - of a completely imaginary car.

Yes, Sundstrom is a bit different than other folks. But his memory skills come from years of self-motivated training and they have a purpose. He competes in the USA Memory Championship contest and, this month, came in second in the country.

Finalists are an elite group known as "mind athletes" with an astonishing ability to memorize huge amounts of text and data in mere minutes. They acknowledge being a lot like Rain Man, albeit with social skills. And yep, they can use their unique brains to count cards and beat blackjack dealers in casinos.

"You wouldn't believe how many people have offered to pay my expenses if I go to Las Vegas with them to count cards," Sundstrom says cheerfully. "I haven't done that.

"And I notice that, since training for the competition, I can memorize long, complex passages from medical journals in minutes, which helped when I took 168 hours of medical courses this year," says the 47-year-old dental surgeon from Chattanooga. "And I now know about 100 poems by heart."

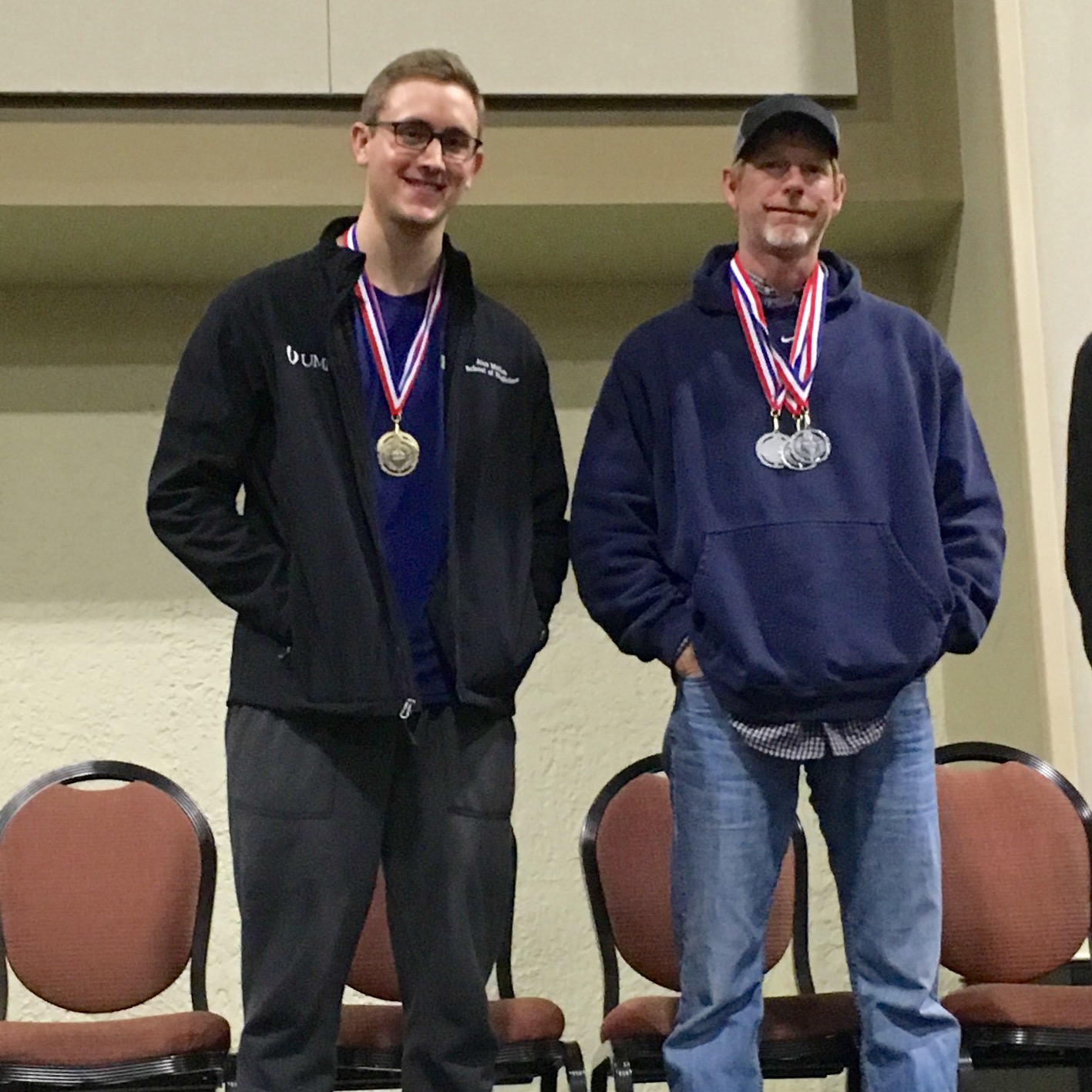

The first-place winner of this year's Memory Championship was Alex Mullen, a 22-year-old medical student. He and Sundstrom have become fast friends "despite our age difference."

In the global memory contests, which take place each year in December, rivals from China, Germany and Scandinavia normally beat the Americans. China financially sponsors its mind athletes and pays their travel expenses to competitions, while contestants from the other 29 participating nations mostly fend for themselves.

And China's drive for the gold has worked; its contestants have won the title of Memory Grand Masters more than any other nation, sparking speculation from the conservative think tank the Heritage Foundation that China may use the quirky contest to train psychological and industrial warfare operatives - or spies.

So the 2015 contest was a stunning upset for China when Mullen won. He took home about $40,000 from the international contest, held in Singapore.

To train for the memory contest, the ultimate chaff-and-wheat sifting is an exercise called the Tea Party in which each contestant meets six guests and must memorize their name, date of birth, favorite pet, car and other minutiae within about 10 minutes.

Sundstrom insists it's fun.

"It's also more effective than memorizing by rote recitation," he explains. "But I have to keep up with my memory exercises and intensify my training before a contest or the memorization gets harder. It is a lot like training your body for athletic competition."

Sundstrom has competed several times in the USA contest and his recent second place is his highest rank yet. In one competition, he met journalist Josh Foer, who morphed into a competitor and won the USA contest then wrote a book about it titled "Moonwalking with Einstein."

In the book, Foer examines strategies used to vastly improve the brain's memory - and whether it translates into comprehension or wisdom or mere recitation. As Woody Allen once joked, "After taking a speed- reading course, I read 'War and Peace' in just 30 minutes. It's about Russia."

Foer notes that neuropsychologists studied some championship memory athletes by scanning their brains during memorization training. "They were engaging areas of the brain that were engaged in two specific tasks: visual memory and spatial navigation, including the right posterior hippocampal region," he writes.

It's a part of the brain that, for centuries, guided humans to their destinations, helping our illiterate cave-dwelling ancestors remember landmarks so they could find their way back from a long hunting party.

In the contest, the successful contestants use an ancient Roman method called a "memory palace" in which they think of a street or house they knew well and place words, facts or numbers in the rooms, on the furniture or along the porches, curbs and windows of the street.

"Memory palaces don't have to be palatial or even buildings. They can be routes through a town or stops along a railway or signs of the Zodiac so long as they are intimately familiar," Foer writes.

But different contests use different methods. Former international winner Dr. Yip Swee Chooi from China used his own body, picturing each of the 56,000 words in the Oxford Chinese-English Dictionary tattooed on a different part of him.

Sundstrom has a new twist on memory palace. He imagines each of hundreds of numbers as a person. His wife is 34; "Three's Company" actress and Thigh Master infomercial queen Suzanne Somers is 00 and Popeye is 99. When Sundstrom looks at a page of numbers, it becomes a story starring people. So conceivably, one story could have Popeye dumping Somers to pursue Sundstrom's wife - if their numbers appeared in the right order.

He also memorizes names by converting them into images. He taught his three elementary school-age daughters all the U.S. presidents in order by using a type of memory palace. George Washington's name is on a washing machine that weighs a ton, for example.

"They loved it," he says. "They weren't even aware it was like homework because it felt like a game.

"I've found it helps me retain what I've memorized if I add action to an image. So I might add the image of a guy who weighs a ton swilling down milkshakes while he sits on the washing machine. I know it sounds like more work to add an additional image and action to help memorize one name; it seems like you're forcing your brain to remember three elements instead of one. But for me, it all flows together naturally and increases my memory capacity."

And yes, there are times when a memory athlete must clean his palace.

"I clear my mind of the numbers and names I learned in the USA championship as soon as I don't need to retain it," Sundstrom says. "I want my energy focused on remembering what's useful and what's enjoyable."

But Sundstrom acknowledges that even his memory is flawed.

"My wife claims she can remember things I did years ago that made her mad and I have no memory of them at all. So she is one up on me."

Contact Lynda Edwards at 423-757-6391 or ledwards@timesfreepress.com.