Photo Gallery

Life interrupted, life regained: At 22, Sarah Harrell had a stroke, forcing her to rebuild everything

I remember telling him, Dustin, I can't lose her. She's only 22.

As she walked into the kitchen of her Red Bank apartment, all Sarah Harrell had on her mind was quenching the thirst that had been on a slow build during a Netflix marathon.

It was Dec. 6, 2013, a Friday.

A vivacious 22-year-old splitting her time between classes at Chattanooga State Community College and working for Southeastrans, a transportation management company, Sarah had received a raise earlier that day and had called her mother, brimming over with excitement. At the close of a week of end-of-semester exams, however, she couldn't muster the energy to go out and celebrate, so she and her roommate, Megan Collyer, grabbed takeout and were binge-watching episodes of "Glee."

As Sarah made her way into the kitchen, however, she suddenly felt numb on her right side. Initially, she thought she'd just been sitting awkwardly on the couch, but the headache that followed was so intense she vomited.

She remembers next to nothing of what happened next - the events of the next few hours would leave her memory and her life in shambles - but she's heard the story and has retold it many times in the last three years. Recounting what transpired, she sounds detached and matter-of-fact, as if summarizing an episode of a TV crime serial.

"Megan walked in and she knew something was wrong," says Sarah, now 25. "I started making faces at her, and she thought it was funny because we always made faces at each other.... Eventually, she said, 'Quit it,' but I couldn't stop."

Sarah's expression seemed to have divided in two - the muscles of one side drum-taut; those on the other frozen in deadpan neutrality.

As she stood there, mute and unresponsive, Sarah's brain cells were dying at a rate of 2 million a minute, 477 miles of brain fiber an hour, thanks to a clot in her middle cerebral artery, a kind of superhighway supplying oxygenated blood to regions of the brain that control movement and speech.

Every second that dam remained in place, her brain was in a state of neurological freefall as it slowly asphyxiated.

Eight days shy of her 23rd birthday, Sarah was experiencing a catastrophic stroke.

Never too young

Many people lump stroke together with dementia and osteoarthritis on the list of conditions that will politely delay until old age before striking. Statistically, they're right. According to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the risk of stroke doubles for each decade between the ages of 55 and 85.

Of the estimated 800,000 Americans who suffer strokes each year, however, about 10 percent are under the age of 45, says neurologist Dr. Thomas Devlin, co-director of the Southeast Regional Stroke Center at Erlanger hospital.

"Stroke can affect anybody at any age, regardless of who they are," he says.

But when strokes occur in younger patients, the potential for neurological and physical impairment isn't measured in years but in decades, which makes its impact all the more drastic, Devlin says.

"They are in the prime of their life," he says. "They're looking forward to having children and going to college and having careers."

According to hospital records, Erlanger treats about 2,300 stroke patients a year. In 2015, 22 of them were younger than 30.

Regardless of a patient's age, every second counts when it comes to minimizing the lasting impact of a stroke, which some doctors liken to a "heart attack of the brain." Unfortunately, Devlin says, the lingering perception of stroke as a geriatric affliction can delay treatment when it strikes earlier in life.

"If you're a young person, you may be having a stroke - and we see this not infrequently - you go to a hospital and get misdiagnosed," he says. "[Then] they've missed that critical window for treating patients."

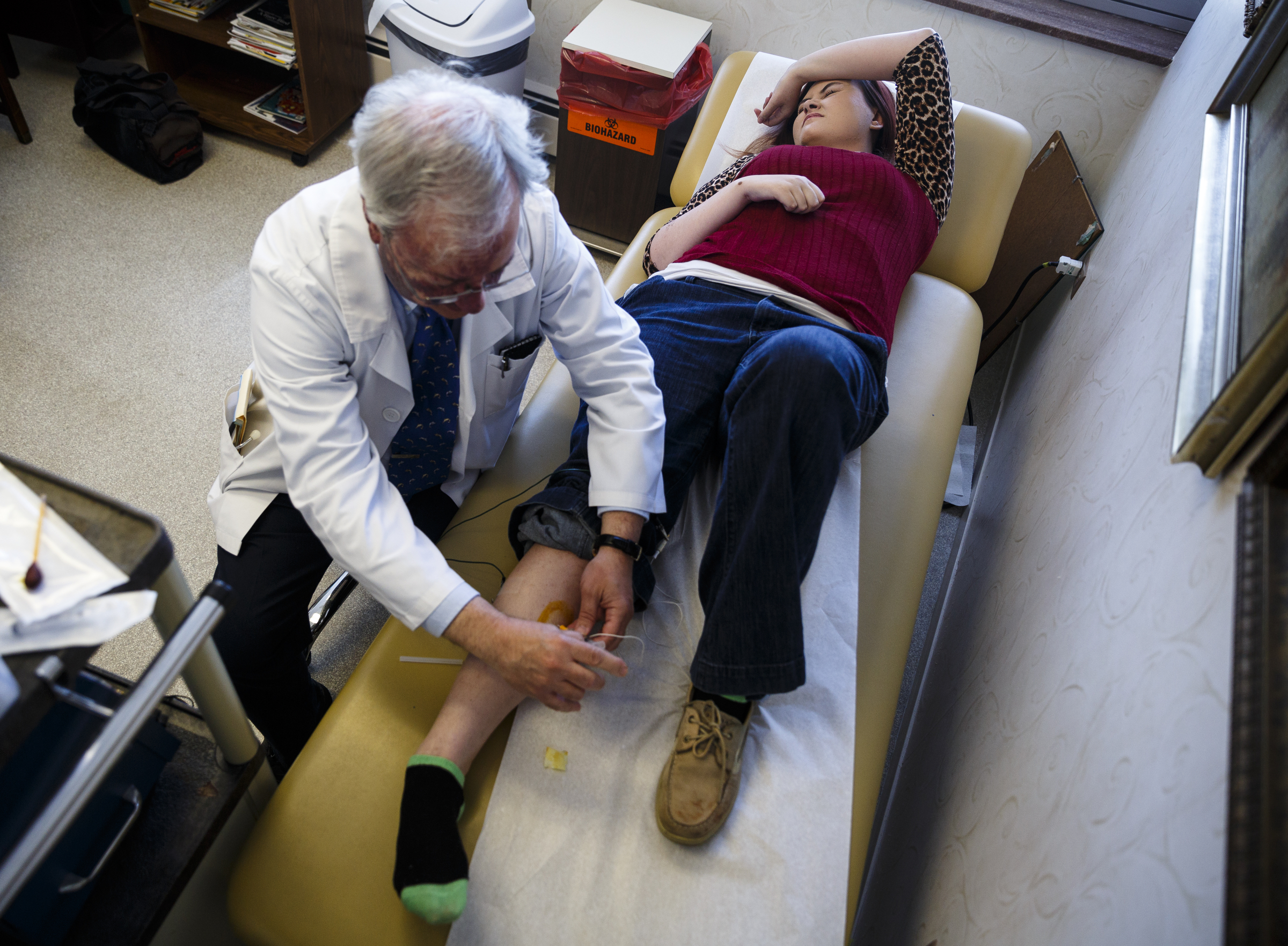

Occupational therapist Sarah Gimbel helps Sarah Harrell perform exercises designed to restore mobility in her right side, which was affected by the stroke she had in 2013 at age 22. Sarah has two weekly appointments at Patricia Neil Rehabilitation Center in Knoxville, and the therapy has helped restore much of her mobility, language and memory.

Occupational therapist Sarah Gimbel helps Sarah Harrell perform exercises designed to restore mobility in her right side, which was affected by the stroke she had in 2013 at age 22. Sarah has two weekly appointments at Patricia Neil Rehabilitation Center in Knoxville, and the therapy has helped restore much of her mobility, language and memory.Getting there

The third of Kathy Wolfenbarger's three children, Sarah was popular at school, a "social butterfly," her mother recalls. Growing up in Sevier County, she amassed a crowd of friends as she flitted from activity to activity - cheerleading, modeling, basketball, color guard, dance team. In photos on her Facebook page, she's laughing and smiling, almost always at the center of a group.

Despite her daughter's popularity, Wolfenbarger says she was a good student and a driven achiever with a stubborn streak a mile long.

"When Sarah wanted to do something, she was going to do it," her mother laughs. "You weren't going to tell her any different."

When she graduated from Pigeon Forge High School in 2009, Sarah decided to enter the pre-med program at Tennessee Technological University, a 2-1/2-hour drive away in Cookeville, Tenn. Her mother suggested she save money by enrolling at Walters State Community College in Morristown, Tenn., less than an hour from home.

Sarah decided her mother was wrong and enrolled in Tennessee Tech.

After two years in Cooke-ville, she followed a boyfriend to Chattanooga, where her group of friends grew even larger.

"That's just the way she was," Wolfenbarger says. "She was just into everything. She was my wild child. She knew everybody, and everybody knew her."

In a sense, that girl died three years ago.

'I knew it was bad'

As Collyer stood in the doorway to the kitchen, confronting the eerie spectacle of Sarah's rictus grin, the possibility that she was witnessing a stroke never occurred to her. Sarah hadn't mentioned feeling sick in any way. They'd been laughing and watching TV minutes earlier.

"It just came out of literally nowhere," recalls Collyer, now 24. "I've had friends' grandparents or parents have strokes, but I didn't know what the telltale signs were. I was clueless."

Thinking Sarah might be on a prescription medication or having an allergic reaction, Collyer called Wolfenbarger. Alarmed, Sarah's mother told Collyer neither was a possibility and to call 911 immediately.

"I didn't know it was a stroke," Wolfenbarger says, "but I knew it was bad.... I got a phone call and my whole life changed."

Five minutes and 10 million brain cells later, emergency responders arrived at Sarah's apartment. About half an hour after the stroke began, Sarah was wheeled into Erlanger.

Neurologist Dr. Abdelazim Sirelkhatim was the first to see Sarah when the ambulance arrived. Her paralysis and inability to communicate or understand commands were telltale signs of a stroke, and she was placed on the hospital's fast-track protocol to ease the clot's stranglehold on her brain.

During the triaging process in stroke cases, doctors evaluate the degree of neurological impairment and damage using a symptomatic scale defined by The National Institutes of Health. At zero, there is no impairment, and a measurement of 14 or higher is considered "massive."

Sarah's stroke was rated at 22.

The gold standard

Since its approval by the Food and Drug Administration in 1996, the use of tissue plasminogen activator, an intravenous medication that activates clot-dissolving proteins in the body, has radically improved stroke treatment. TPA has proven so effective, it is considered the "gold standard" and is recommended as a first-response application in the 87 percent of stroke cases like Sarah's, which involve clots.

The use of TPA is approved up to three hours after the onset of symptoms but, as with all aspects of stroke treatment, doctors live by the mantra "Time is brain." At Erlanger, the benchmark is to use TPA within a window of 20 minutes after arrival. Sarah was treated within 15.

However, the drug loses its effectiveness in stroke cases involving clots measuring 8 millimeters or smaller. At 2 centimeters - more than three-quarters of an inch - the blockage in Sarah's artery was 2-1/2 times larger than the recommended size; it threatened an area of brain larger than a baseball.

"TPA can work, but it didn't work well in these bigger clot burdens because it was just so much clot to try and resolve," says Erlanger neurointerventionalist Dr. Blaise Baxter. "It would take hours and hours and hours and, by then, the damage was done."

Once it became clear that TPA alone wouldn't suffice, Sirelkhatim, Devlin's co-director at the Southeast Regional Stroke Center, ordered a mechanical thrombectomy to attempt to physically remove the clot. In a thrombectomy, doctors begin by opening a pathway to the femoral artery at the top of the leg. They then navigate catheters through the circulatory system to the blocked artery. Once they arrive, they use suctioning devices and stints that deploy a kind of net designed to grasp clots and pull them out. Baxter refers to this suite of tools as "clot suckers" and "clot pluckers."

Speed is paramount in stroke response, but Sarah's age was on her side. Experts say younger brains have greater neuroplasticity - the ability to safeguard some neural function by rerouting around damaged areas - allowing them to "tread water" while doctors work and adding a few precious minutes to the clock.

Although complete clot removal is the ultimate goal in thrombectomies, it's not always possible. Baxter was able free up the main artery, but pieces of the killer clot were still partially lodged like stubborn squatters in Sarah, blocking smaller blood vessels supplying areas of the brain that were already damaged beyond repair.

A long night

As the stroke response teams at Erlanger worked to save Sarah, her mother was driving furiously on a midnight blitz to Chattanooga. As fast as she was going, she remembers the trip as a kind of elastic nightmare that stretched out far longer than the two hours it normally required.

"That has to be the longest drive I've experienced in my entire life," she says. "They weren't even sure she would make it out of surgery. I felt like my car was up on cinder blocks and just spinning; I didn't seem to be getting anywhere.

"Looking back on it, I was totally numb," she says. "I kept thinking, 'This is not happening. This is not happening.'"

The reality of Sarah's condition didn't fully solidify until Wolfenbarger called Dustin, her second son and Sarah's older brother, and told him what had happened.

"I remember telling him, 'Dustin, I can't lose her. She's only 22.'"

When she finally arrived at Erlanger, the horrors she faced only seemed to multiply.

Blood flow to Sarah's brain was mostly restored, but she wasn't out of the woods. For 24 to 48 hours after clot removal, Erlanger considers stroke patients to be in "life-critical condition" because of the risk of additional complications.

Once Sarah was moved to the intensive care unit, Wolfenbarger received a blunt prognosis from Sirelkhatim, one that involved frequent use of the word "if" with respect to her daughter's prospects for recovery.

She might be mute.

She might fail to recognize her loved ones.

She might not be able to walk.

"I knew what he was saying, but I don't know if I wasn't accepting it or just numb," Wolfenbarger recalls. "I couldn't react to it. In my mind, I'm thinking, 'OK, my daughter is going to be a vegetable for the rest of her life. How did this happen?'"

Twice for 'yes'

Sarah's first blink in the ICU the next evening was almost an act of defiance.

"She opened her eyes," Wolfenbarger says, pausing briefly to gather herself as the memory floods back. "That was just unbelievable. It was just fantastic."

Hardly daring to hope, she realized Sarah couldn't speak but asked her to blink her eyes in response to questions - once for no, twice for yes.

"I asked 'Do you understand that?'"

Blink. Blink.

"I said, 'Do you know who I am?'"

Sarah's eyes closed twice more.

"I said, 'Am I your mom?'"

A final affirmative.

Wolfenbarger was convinced, but Sirelkhatim remained doubtful.

About 24 hours later, Sarah's friends were in the room and announced that Auburn University, Sarah's favorite football team, had won the Southeastern Conference Championship. When she heard this, Sarah slapped the bed with her left hand, the closest to a clap she could manage with only one functional arm.

That cinched it.

"I told Dr. Sirelkhatim, 'I told you. She understands,'" Wolfenbarger says. "The man literally stood there with tears running out of his eyes. Nobody believed that this child would ever wake up and know anything."

During a visit to Chattanooga, Sarah shops at Victoria's Secret with one of the few friends who have kept in touch with her since the stroke. Some of her friends have not kept in contact and her mother, Kathy Wolfenbarger, says she understands. "At 22 or 25, most kids think, 'It's not going to happen to me. It'll happen to somebody else. I'm invincible,'" she says. "They don't know how to deal with it, and they don't want to deal with it."

During a visit to Chattanooga, Sarah shops at Victoria's Secret with one of the few friends who have kept in touch with her since the stroke. Some of her friends have not kept in contact and her mother, Kathy Wolfenbarger, says she understands. "At 22 or 25, most kids think, 'It's not going to happen to me. It'll happen to somebody else. I'm invincible,'" she says. "They don't know how to deal with it, and they don't want to deal with it."A head full of holes

The girl who woke up in the ICU was not the same one who had arrived. Her right side was paralyzed, even digestion on that side of her stomach was affected. She was unable to speak.

Sarah couldn't remember being the "wild child" that Wolfenbarger raised. As it strangled her brain, the clot had all but erased her long-term memory. She turned 23 at Erlanger, but she lost far more years than she gained during her stay there.

Memory issues are a common side effect of strokes, affecting about one-third of patients, experts say. Short-term memory loss is more common but, in Sarah's case, her entire childhood and adolescence are a haze. The scraps she has left are a tattered, insubstantial patchwork of half-remembered people and events.

She can recall some glimmers of her life in Red Bank, including the Christmas tree she and Collyer had in their living room. Even in the early days of her recovery, she recognized her roommate, remembered her face, but insisted on calling her "Katie girl" instead of Megan.

She doesn't remember going to high school, but she remembers her biology and history teachers. She recalls being at Tennessee Tech before moving to Chattanooga, but she can't remember life on campus or what classes she took.

"We've done a lot to try and jog her memory, and sometimes it'll work and sometimes it won't," her mother says.

And her mother? Even with memory that was more vaporous than solid, the relationship was a rare certainty. When her ability to speak began to rematerialize in the weeks after Sarah woke up, her mother posed a question.

"I asked her one day, 'If you have no long-term memory, how do you really know I'm your mom?'" Wolfenbarger says. "She told me, 'You were right there with me, and you've had to do everything for me, from bathing me to taking me to the bathroom. Nobody but my mom would do that.'"

'What the heck?'

In the first few weeks after she woke up, Sarah's emotions would arrive in confused torrents, a common post-stroke condition known as the Pseudobulbar Affect. She would experience bouts of rage or find unexpected hilarity in someone's death.

Early on, Wolfenbarger says, it was like the stroke had catapulted Sarah back in time. She would bounce for joy in childish delight at something as simple as finding a straw in her cup to make it easier to drink.

"Sarah could be a 23-year-old or she could be a 12-year-old in her personality," her mother says.

Compounding her recovery, Sarah had to overcome issues with aphasia, a communication disorder caused by neurological damage to the language centers of her brain. At first, the only phrase Sarah could muster - and to which she gave an infinity of meaning - was "What the heck?"

"That was it," Wolfenbarger laughs. "Everything was, 'What the heck?'"

When she was finally able to say more, she would speak about herself in the third person and confuse people's genders in conversation. As often as not, she would say "no" and mean "yes," or vice versa.

After transferring from Erlanger to Knoxville for a month of in-patient therapy, Sarah moved into her mother and stepfather Ronnie's home in West Maynardville, Tenn.

Early on, she was struck by all she had lost. In the space of a few seconds between the couch and the kitchen in her former apartment, it seemed as if her entire life had slipped through her fingers. Her body felt like a burden and, as a result, she says, she felt like a burden to her family.

Daily tasks such as brushing her teeth or getting dressed were challenging struggles with the weakened, unresponsive fingers of her right hand. She could no longer shave her legs or go to the bathroom alone. Frequently, she experienced nerve pain so excruciating she would beg her mother to cut off her leg. When it didn't leave her in agony, the pain turned to itching, a condition experts say affects about one in 500 stroke patients.

For most of the first year after the stroke, she was wheelchair-bound. When she finally walked, she had to use a cane, and her right foot felt twice as heavy and turned inward, dragging behind her like a ball-and-chain of flesh, blood and bone.

Worse, the friends who had once filled her life and Facebook albums - the ones who gathered en masse in the waiting room at Erlanger - drifted away like dandelion fluff in a stiff breeze. Her mother says that hurt Sarah, but her friends' reluctance to face the devastation that had happened to one of their own was understandable.

"At 22 or 25, most kids think, 'It's not going to happen to me. It'll happen to somebody else. I'm invincible,'" Wolfenbarger says. "They don't know how to deal with it, and they don't want to deal with it.

"When we were at Erlanger, you couldn't have stirred that room with a stick. They were all at that hospital."

Seeing the challenges Sarah soon would be facing, however, Wolfenbarger turned to her husband and made a prediction: "All these kids are going to disappear. They're going to go away. It'll be me, you and Sarah left holding the bag."

"I knew it was going to happen," she says.

Pushing ahead

Why Sarah experienced a stroke remains a mystery. She had none of the standard risk factors. She wasn't overweight; she didn't have high blood pressure or diabetes. Although she smoked, she didn't have a cigarette in her hands 24/7. There was no history of stroke in her family.

Despite batteries of tests and extensive bloodwork, her case has been labeled "cryptogenic" - of obscure or unknown origin - by her doctors, who say that's the outcome in about 20 percent of strokes.

"In the past, it used to be 35 percent," Sirelkhatim says. "Now, we're looking at more and more causes."

The stroke tilted much of Sarah's life off-axis, but one aspect of her personality that remained steadfast was her sheer, unbridled determination. Therapists and family members say her inability to accept her own limitations and to doggedly pursue a goal has fueled her recovery. Doctors have described her improvement as "amazing."

"We learned to walk again," Wolfenbarger says. "We learned to talk again."

Melanie DeWitt, Sarah's physical therapist at Patricia Neil Rehabilitation Center in Knoxville, says Sarah has "not been one to sit passively."

"Maybe that happened at the beginning when she was still in shock and dealing with what's going on and depressed," DeWitt says, "but she's been able to pick herself up and push herself."

On many levels, Sarah says, the stroke was a kind of forced regression.

"I pretty much had to grow up all over again," she says. "I thought, 'I'm never going to live again.' I told my mom, 'Can you please just let me die? This is awful.'"

But eventually her stubborn streak won out and she decided to face down her challenges rather than allow herself to be overwhelmed by them.

"I decided that, 'I'm going to do whatever I can to get out of this mess,'" she says. "It just dawned on me, 'Maybe I should just be thankful that I'm still here and that I can try to work on it and get better.'"

There are still signs of the stroke's impact. Tightened muscles in her leg force her foot to turn inward, hampering her ability to walk without a brace. Occasionally, she struggles to remember words, forcing her to pantomime what she means, a quirk her mother jokingly calls "playing charades."

She will probably never completely recoup all the brain and motor function stolen by the stroke, but she could continue to progress for years to come, Sirelkhatim says.

"I tell most of my stroke patients that we don't see 100 percent recovery," he says, "but continuous improvement after stroke damage, even after five years or six years? We do see that."

When she finds her physical abilities lacking, Sarah has a knack for working out inventive means of circumventing her limitations. Tying shoelaces poses a challenge for her stiff right hand, so she uses her teeth to grab the laces.

Walking past her daughter's room one day, Wolfenbarger saw her lying down with her head dangling over the foot of the bed. Sarah was trying to figure out a way to put her hair into a ponytail using only her left hand. After eight months of working at it every day, she finally figured out a solution.

Letting go, moving on

Before the stroke, Sarah felt confident in her looks. Not vain, she says, but sure of herself. Afterward, however, she felt like she was constantly stared at - a spectacle - when she was out in public.

"I thought I was ugly," she says. "I wanted to stay in the house all day."

She'd never put much stock in cosmetics in the past but, in the thrall of self-doubt, wearing makeup became a way to guard against scrutiny. She watched YouTube tutorials to learn new cosmetic techniques and tried them out on herself. Blush became her armor; foundation her shield.

"[Makeup] was a confidence thing," she says. "It helped a lot.... I found this passion, and it kept me busy, kept me motivated."

Tucked into a corner of her mother's house across from a bathroom, Sarah's bedroom is a veritable shrine to the two great loves of her life: Auburn football and cosmetics.

Opposite a bed topped by an Auburn Tigers blanket, her makeup collection sprawls across a turquoise-and-black table and a rolling cart with seven pull-out baskets, one of them overflowing with more than a dozen tubes of mascara.

Last year, Sarah was accepted into an intensive, month-long makeup artistry program at Knoxville-based War Paint Academy. When Wolfenbarger called to explain her daughter's limitations to school founder Christian McNally, he knew there was no way he could say "no." Not because Sarah was a stroke victim, but because she exuded dedication and passion.

"I said, 'All right, let's do it, sister,'" he laughs. Once in the school, Sarah managed to keep up during the course despite working with only one hand, he adds.

"The proof's in the pudding," he says. "She's a good little makeup artist. She outshined a good 60 or 70 percent of the class."

Since graduating from the program, Sarah has taken on jobs doing makeup work, including weddings and working with models during Knoxville Fashion Week. Fittingly, she advertises her services on business cards emblazoned with the tongue-in-cheek business moniker: Brush Strokes.

Forward momentum

After years of feeling held back and reined in, Sarah's life has accelerated on nearly every front in the months leading up to the third anniversary of her stroke in December.

In an effort to raise stroke awareness, especially among young people, she has made numerous visits to area schools. She also was tapped to throw out the first pitch at a Chattanooga Lookouts game in May in honor of Stroke Awareness Month.

For years, Sarah says she's felt torn between a desire to live alone and concerns about her ability to care for herself, but in July, she survived a week alone when her mother and father-in-law left her to take a trip to Oklahoma.

"It was like a test," Sarah says. "My parents were ecstatic because, for the first time, I was by myself, fending for myself.... I didn't burn the house down, which was good. My parents know that I'm ready to move out."

And soon she will have somewhere to go. Her brother, Dustin, is building her a house nearby, and she's already started planning the furnishings.

"I've already got a dining room table," she says.

She's also ready to hit the road. Almost since she woke up in the ICU, Sarah says, the loss of her driver's license has been a constant reminder of the freedom and independence she lacks.

"I feel like I'm 16 years old - or less than that - because I have to be taken everywhere by my parents," she says. "Now it's like, 'I'm 25 years old. I want to drive. I want to live by myself.'"

Commonly after a stroke, irritation caused by the buildup of scar tissue in the brain can lead to symptomatic epileptic seizures. In August 2015, Sarah experienced a seizure that delayed her ability to take the driving test for more than a year until she was released by her psychiatrist and neurologist. They gave their approval in June, and Sarah is on the waiting list for the exam.

Wolfenbarger says she's excited to see her daughter's life gaining some forward momentum, even though she worries it might be a case of too much, too fast.

"I think actually being out on the road is going to be more chaotic than what she's thinking, and she'll have to take it slower than she thinks she's going to have to," Wolfenbarger says. "Her driving scares me, but I'm excited for her."

A few weeks ago, Erlanger sent copies of Sarah's CT scans to her mother. Looking through them, she says, she's reminded how easily the stroke could have won, but she's convinced there's a reason it didn't.

"I was very close to losing my daughter. I knew that before, but it was that realization all over again," she says. "We thank God every day. He chose to keep her on this earth, and I'm so grateful for it."

Contact Casey Phillips at cphillips@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6205. Follow him on Twitter at @PhillipsCTFP.