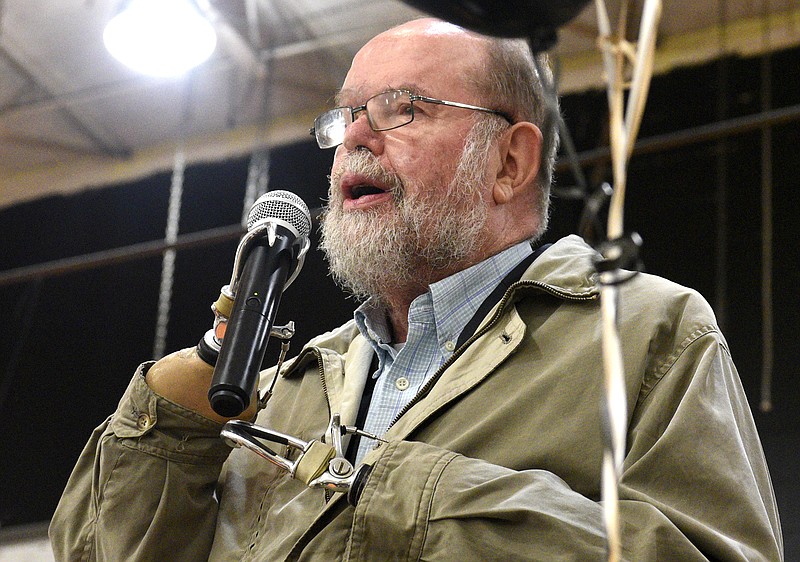

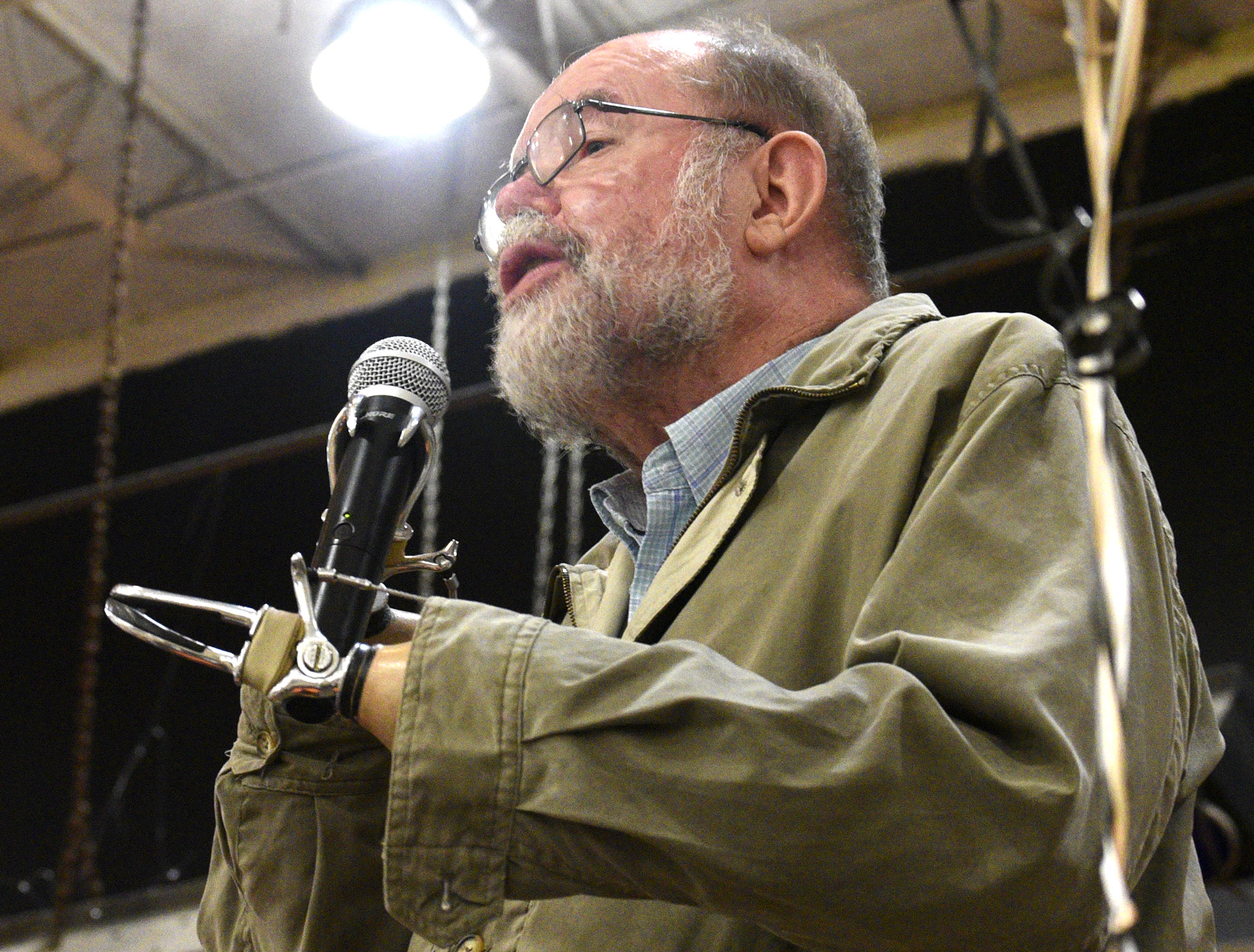

As a white priest who fought for South African blacks to be treated equally, Father Michael Lapsley turned from his pacifist beliefs of nonviolence to join the African National Congress until Apartheid ended. The fight cost him two limbs and one eye.

Lapsley has since used his experiences to fight against social injustice around the world, and he came to Chattanooga last month to tell people how he had healed, and to lead others who suffered traumatic experiences toward healing.

"If there is to be peace in the world, there has to be peace in the nations," said Lapsley. "Peace in the cities and peace in the homes and actually then peace in the heart. So then we really see this work as healing the world."

In April 1990, a letter bomb exploded blasting off Lapsley's hands, shattering his ear drum and nearly disconnecting his eye. The explosion left him blind in one eye and his sight diminished in the other.

South African Apartheid officials meant to kill him when they mailed the bomb to his home in Harare, Zimbabwe in 1990, according to Lapsley. He was a white man who joined what many people considered a black struggle. Yet Lapsley survived the bomb. As he healed, he helped heal his country and now takes his healing process around the world.

More Info

For more information about Lapsley’s upcoming visits to Chattanooga contact Cathy Harrington at 231-301-3177.

He calls his program Institute for Healing of Memories. It's based in Cape Town, South Africa. He also has an office in New York. The institute encourages emotional healing by providing listeners for people in need, and a safe place for people to share their stories. Lapsley teaches that it's possible to redeem bad experiences and allow them to motivate good works.

"None of us will leave this earthly life without varying degrees of trauma. If we don't deal with it, it will continue to effect us and stymie our lives," said Lapsley.

When people neglect to deal with the past, they create the wars of tomorrow. Effective development requires a journey of healing, he said.

Unitarian Universalist Church Minister Cathy Harrington believes in Lapsley's institute so much that she landed a Unitarian Universalist Veatch grant, which are used to fight social injustice, to bring Lapsely from South Africa to Chattanooga this fall so he could facilitate the Institute for Healing of Memories in Chattanooga.

He shared his story with students at Orchard Knob Middle School in October. And he led a Healing of Memories facilitator training at the church the same month.

It's the same training he used to bring healing to Rwanda when speaking to people still hurt by the 1994 Rwanda genocide. He met with people there whose family members where killed and women who bore children or were infected by the HIV virus as a consequence of rape. And he spoke with people who had perpetrated crimes. They spoke about what needed to be done to prevent repeating the events. After the meeting several perpetrators explained how they would work to improve the country.

Lapsley also led Institute for Healing of Memories workshops in Asia, the United States and South Africa.

Harrington plans to host an Institute for Healing of Memories program for veterans in March at the Unitarian Universalist Church on Navajo Drive.

And Lapsley, who worked with Archbishop Emeritus Desmond TuTu on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa, is expected to return to Chattanooga in May for another training.

Chattanooga and Cape Town share similarities in that both countries have drugs, gangs, violence and inequality, said Harrington.

"Father Lapsley's work in Cape Town is very similar to Chattanooga," said Harrington, whose daughter was murdered in her home near Napa, Calif. in 2004.

"There is a divide, but when you can see someone else's humanity, even the offender's humanity, then you began to heal yourself. But if you hold on to the anger and the revenge, you'll never heal. You hurt yourself."

Contact Yolanda Putman at yputman@timesfreepress.com.