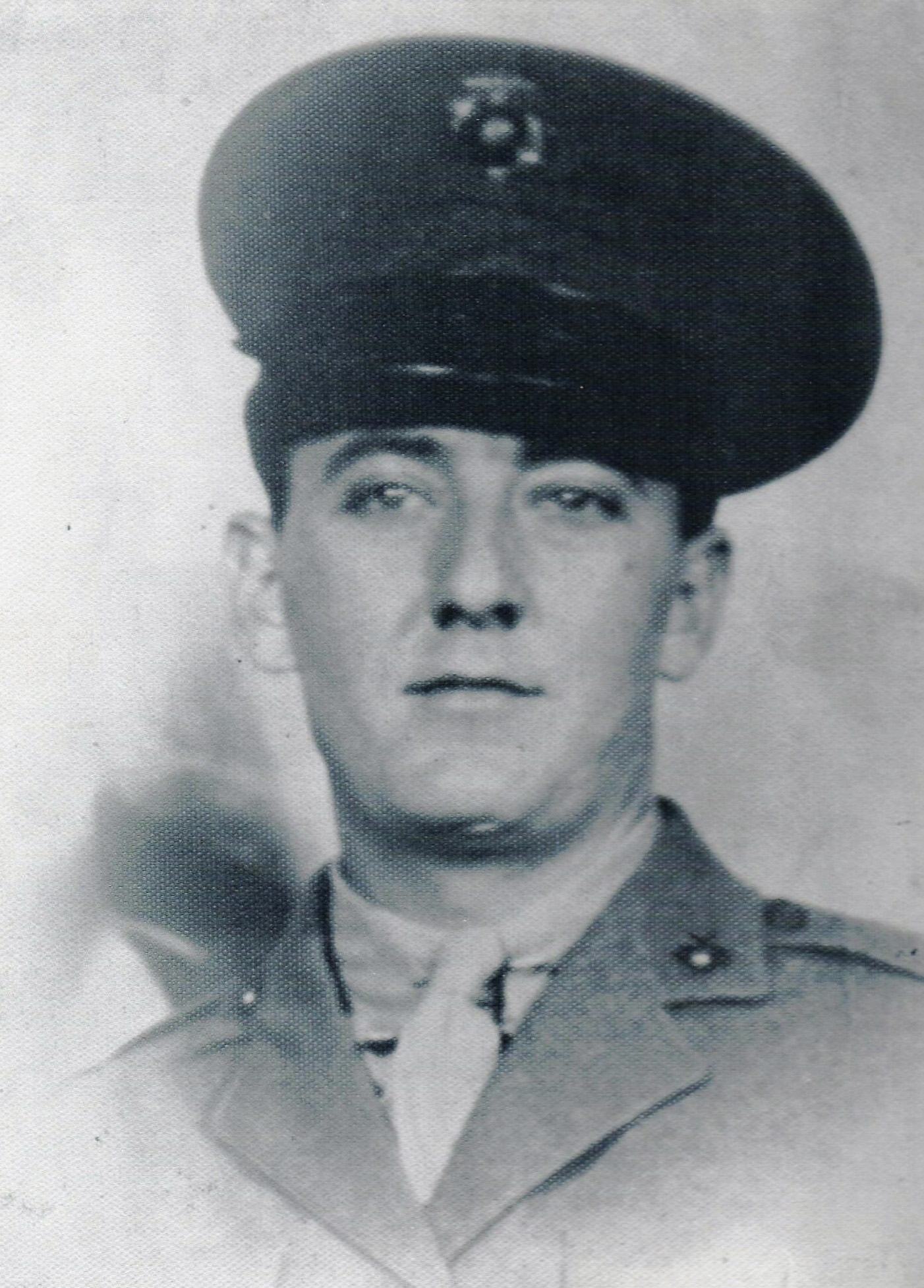

On Aug. 25, almost 74 years after his death in the invasion of Betio Island in the Tarawa atoll, the body of Marine Cpl. Henry Andregg Jr. was returned to his native Tennessee for burial with full military honors in Chattanooga's National Cemetery. Andregg, of Whitwell, served as a driver of an amphibious tractor, a vehicle that played a pivotal role in the costly victory in the three-day battle, Nov. 20-23, 1943.

Betio, in the Gilbert Islands of the South Pacific, had an airfield and a garrison of 2,500 elite Japanese Marines and 2,200 Korean laborers. The island's importance rested in its value as airbase and staging area for subsequent U.S. invasions of other enemy-held islands.

The hot, overcrowded transports bearing the 2nd Marine Division embarked almost two weeks before the invasion from Wellington, New Zealand.

U.S. Marines bear the casket of Cpl. Henry Andregg, Jr., of Whitwell, Tenn., from his funeral with full military honors at the Chattanooga National Cemetery for burial on Friday, Aug. 25, 2017, in Chattanooga. Cpl. Andregg was killed during the Battle of Tarawa in World War II's Pacific Theater, but his remains were only recently identified through DNA testing. Previously interred at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu, Cpl. Andregg was returned home for burial nearly 74 years after his death.

U.S. Marines bear the casket of Cpl. Henry Andregg, Jr., of Whitwell, Tenn., from his funeral with full military honors at the Chattanooga National Cemetery for burial on Friday, Aug. 25, 2017, in Chattanooga. Cpl. Andregg was killed during the Battle of Tarawa in World War II's Pacific Theater, but his remains were only recently identified through DNA testing. Previously interred at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu, Cpl. Andregg was returned home for burial nearly 74 years after his death.On Nov. 20, following heavy bombardment of Betio by ships and carrier-based aircraft, the first wave of landing craft set out for the targeted beaches at 9 a.m. Marines had already endured hours in their small boats. Many of the Higgins boats, which carried the majority of the invading force, ran aground on barely submerged coral reefs more than half a mile from shore. Their ramps were dropped in water that rose to the shoulders of disembarking Marines. They were immediately exposed to a murderous crossfire from well-fortified bunkers that had survived the pre-invasion bombardment. Many Marines never reached shore. Others had to abandon their weapons and packs. Radios were lost or damaged, limiting contact with supporting ships.

Marines held a narrow strip of beach bordered by a 3- to 6-foot seawall constructed of palm logs. Their commanding officer suffered multiple wounds but continued to lead. Ammunition, water, food and medical supplies were limited. Most medics in the landing force had either been killed or wounded. Wounded Marines who could hold a weapon continued to fight. Any attempt to advance over the seawall failed. Despite supporting gunfire from naval ships and repeated air attacks, the Japanese defenders could not be dislodged. The invaders were trapped.

Amphibious tractors (amtracs) could surmount the shallow reefs and deliver personnel and supplies onto the beachhead and carry wounded back to the ships. An earlier version of the vehicle had little protective armor. A newer version featured thicker armor-plate and more-powerful machine guns. Each amtrac, with its three- to five-man crew, could carry 18 fully equipped Marines or 4,500 pounds of cargo. A fully-loaded amtrac could travel at 6-7 miles per hour in water, 12 mph on land. Amtracs could not breach the seawalls entrapping the invading force.

The amtracs were subjected to unrelenting fire from machine guns, mortars and artillery pieces as they shuttled back and forth between troop and supply ships and the shore. As soon as an amtrac unloaded Marines and supplies, it was filled with seriously wounded fighters who were ferried to medical care. By the end of the first day of battle, only 35 of 120 amtracs that had entered battle had survived. Many crewmen had been killed or wounded. Without the vital lifeline of personnel and supplies the amtracs provided, the Marines on shore would likely have been annihilated. Transport of wounded to shipboard medical care saved many lives.

The landing force held its narrow beachhead through the night.

A second wave of Marines landed the next morning, sustaining heavy casualties. As the day wore on, Marines, supported by naval gunfire and nonstop bombing, slowly advanced into the densely defended island. Victory was finally achieved on the third day of battle. One thousand Americans lost their lives. Two thousand were wounded.

Controversy surrounded the invasion of Tarawa. The public was shocked to learn of the casualties. For the first time, U.S. newspapers carried photographs of the bodies of Marines where they had fallen. Generals and admirals debated tactics for months. Nothing, however, could diminish the incredible bravery of Marines such as Cpl. Andregg in achieving victory when disaster had threatened.

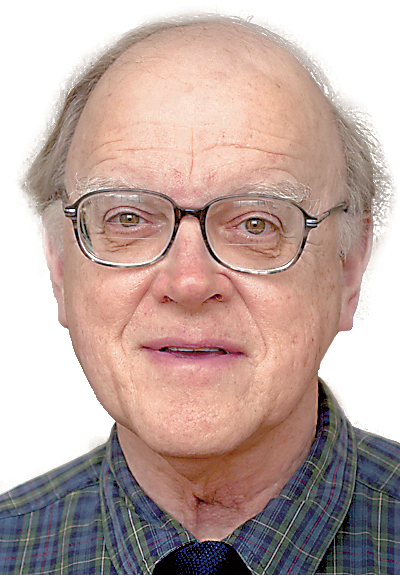

Contact Clif Cleaveland at ccleaveland@timesfreepress.com.