When I was "a little whippersnapper," as my Uncle Watt used to call me, I lived with my mother and two younger brothers in a small farming community a short ways down the two-lane pike from Columbia, Tennessee. Old country people and their children and their children's children grew up and lived there for the biggest part of their lives.

Occasionally, one of the offspring would head for the big city to follow their dreams of being somebody famous. Give it a little time and they came on back home. The bright lights went out. Nobody got famous. They shook it off and fell back into where they left off: Farming.

It was like having one great big happy family out there in the country.

Grown-ups, whether they were or weren't your parents, looked after each other's kids and knew all their names and where they lived. It was hard to get anything past anybody. They seemed to be tuned in to the same adult frequency. By the time I got home, my mother knew where I'd been and what I'd been up to.

Ninety-nine percent of the kids with whom I attended school lived on farms and had their chores to perform as soon as they got off the school bus. I was a teacher's son. We lived in a little trailer on the school's property. There really wasn't much for me to do other than show up for supper.

Consequently, I had plenty of time to do odd jobs and run errands for grown-ups. I pretty much did something for everyone in town at one time or another. I split up firewood, hauled in coal, raked yards and swept down sidewalks. Occasionally, I could talk one of the town's elderly ladies into buying some fish from me. Sun perch were my specialty.

From the time they'd place their order, I could be back within an hour or so with a dozen fresh perch. They'd pay me a half-dollar. I wasn't gonna get rich fishing, but the way I looked at it was that I was making money doing what I loved to do. A man can't ask for any better.

One of the best fishing holes of Cathy's Creek ran in front of Mr. Glassman's farmhouse. He didn't have a big spread - a few acres of corn and a hillside. He kept two cows up close to the fence and had a bunch of chickens. His house sat right in the middle of a circle of tall trees. The back porch door and a roll-out picture window looked onto the creek.

You could see him sitting back there. From across the creek in the shade, he looked like he had gray skin. Mean eyes. The few times I saw him up close at the store, you couldn't help but notice all the hair he had in his ears and nose. He was a thin man, disheveled, a constipated expression on his face.

Mr. Glassman was of the mind that all the fish swimming out in front of his house were his. He wasn't the sharing kind. When he saw Prince and me down there, he'd open his back door and holler, "You'uns best be leavin' my fish alone."

He pounded wooden stakes in the ground on both sides of the creek to mark his territory, about a hundred feet long. I'm pretty sure he couldn't have legally enforced anything. Still, no sense in rocking the boat. He was a cranky old man.

Once, I walked across his bridge and up to his porch to see if he needed any work done. I knocked on the front screen door. He was sitting on a recliner with the TV on. He just stared at me.

I put my face and hands right up next to the screen and told him that I could see him. He got up and walked to the back. Pretty soon, from around the house, came four big dogs, showing their teeth and barking up a storm. He'd turned his dogs loose on me. Like I said, he was a mean old man.

I sprinted through the chickens and out of his yard and hightailed it back across the bridge. He was yelling something at me. I didn't stick around to ask him what.

I guess he didn't want to be disturbed. I'd seen all those "No Trespassing" signs he'd posted by the bridge and in several other locations. I'm not sure why I didn't think those signs applied to me. I thought trespassing meant sneaking. From then on, I knew the difference.

You don't need much to fish for perch. Maybe 10 feet of fishing line and a hook. You tie the line onto a limb and knot up a small stick halfway down. That's your bobber. Push over a few rocks, pull up some worms, and you're in business.

I fished on this side of Mr. Glassman's bridge, just past his stakes in the ground. It wasn't good fishing. They just weren't biting that far down. I doubled down on my worms. Nothing. Not even a nibble. The other fishing hole was a mile and a half up the road. I'd stay put and hope for the best. Nine times outta 10, I left with my head down and empty-handed.

Blind Remus told me to do what he did. Pray. I was up for anything. I just didn't want to wear out my welcome with God. I figured he had his hands full. For some reason, I kept going back. I was bound and determined to catch a mess of Mr. Glassman's perch. Sometimes, I packed a lunch. Peanut butter and blackberry jelly sandwiches.

When you're 10, you can't get much better than eating PBJs and fishing. Even if you don't hook anything, it's still a pleasurable experience. Being a country boy has its advantages.

I looked back upstream and saw Mr. Glassman looking out his back window at me. It was the only time I saw him smile. My agony was his pleasure. Him smiling at my frustration was the last straw. I decided to bring out the big guns. I prayed, and I prayed some more. Every time, I prayed for the same thing. To please let me catch all of that old man's fish.

Just as I figured, the Almighty was busy with way more important matters. At my young age, I was of the impression that God answered all prayers. At night, I'd kneel down in front of my bed and apologize to him for all my fishing prayers from earlier in the day.

I waited a few days before I went back to the bridge. I decided that I wouldn't bother God anymore. This would be my last attempt. There's no sense in torturing myself. I tossed the line out, sat back and waited. I bit into my first sandwich. My dog, Prince, jumped on my lap, and I dropped the sandwich in the creek. As I watched it float downstream, here came the fish! A bunch of them.

Change bait. The perch were loving my mini-sandwich concoctions of peanut butter and jelly and red worms. Turns out, they liked pimento cheese and mayonnaise sandwiches just as well. Mr. Glassman stood out back and watched me pull out one right after the other. He wasn't smiling anymore. I tried not to gloat.

I'm not sure why, but I wrote Mr. Glassman a thank-you note and put it in his overstuffed mailbox. I stated that I'd leave his fish alone for a while. I wasn't trying to be a smart-aleck. Maybe just a little. It's just that he was such a mean old grump.

My note may have upset him. But probably not as much as when he noticed that the first two reflector letters of his last name on the mailbox were gone.

Here's hoping that the Lord is as understanding as they say and that he has a good sense of humor.

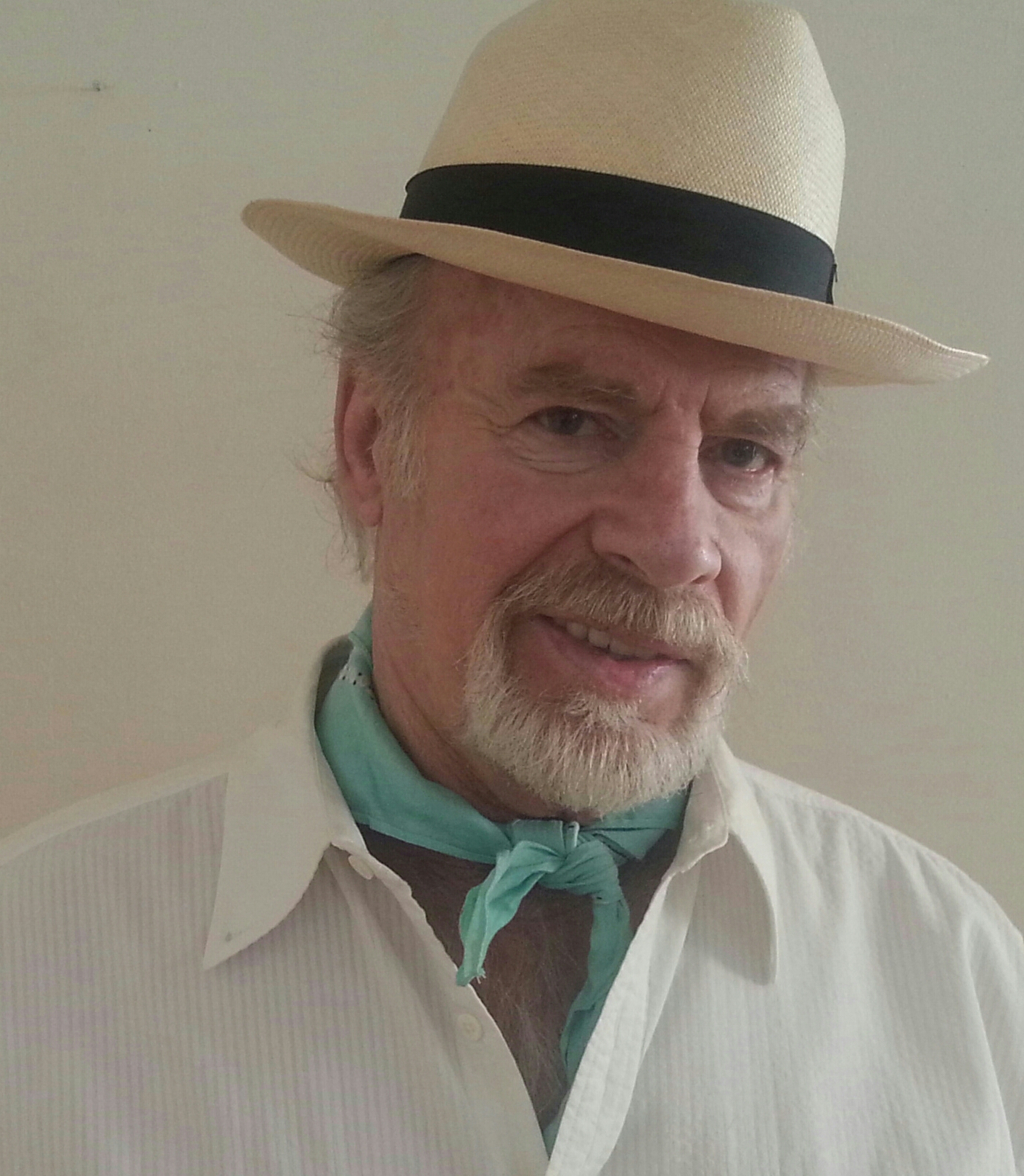

Bill Stamps spent four decades in the entertainment business before moving from Los Angeles to Cleveland, Tennessee. Contact him at bill_stamps@aol.com or through Facebook.