By Paul West

Tribune Washington Bureau

WASHINGTON - President Barack Obama's increasing involvement in budget talks reflects an unspoken reality of Washington's latest mini-drama: No one knows who will get the blame if the government shuts down.

Republicans took the hit when the government last closed its doors, during a similar budget impasse in the mid-'90s. But this time could be different.

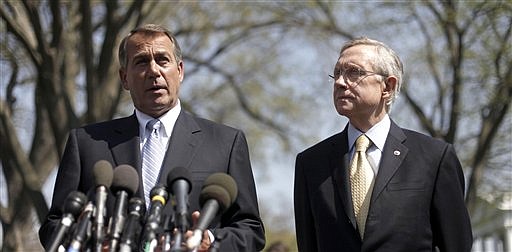

In a possible sign of progress, Obama was to meet again with Republican House Speaker John Boehner and Senate Democratic Leader Harry Reid on Thursday evening. It will be their second White House negotiating session in one day - the first time that has happened and an indication that pressure is intensifying to reach agreement ahead of Friday night's shutdown deadline.

Public-opinion surveys show that both sides could be blamed if Democrats and Republicans can't come to terms. But those polls mean nothing if the government actually starts closing down and politicians begin measuring the public's reaction, including that of prized independent swing voters.

"This is like going into the no-man's land, where there are landmines left and right, and you're not sure which step is a safe one," says Neil Newhouse, a Republican pollster. "Both sides need to make sure that their respective political bases are covered, and neither side wants to appear to give away the store."

In theory, if not reality, Obama holds the upper hand. He's more popular than the Congress, polls show. He has the presidential megaphone and can out-communicate a very diffuse congressional opposition.

But he also has to watch his left flank. Any budget agreement is virtually certain to make deep cuts in liberal spending priorities. Once the details become known, it could revive unpleasant memories for Obama supporters of the lame-duck tax deal he cut with Republicans last December and provoke another angry response.

As the clock ticks down, Obama, congressional Democrats and their Republican adversaries face risks and a bounty of unanswered questions: If the government shuts down, how long will it last? Closing for a few days will likely have only minimal effect, in line with the winter snows that periodically shutter operations. If the impasse persists for several weeks, as was the case in 1996, what happens during the shutdown?

Obama and Reid said it would imperil the nation's economic recovery, though economists play down any significant threat unless a shutdown turned out to be prolonged.

And how does it finally end? Will one party or the other appear to have gained or lost ground as a result?

Already, Democrats have tentatively agreed to steeper cuts than they seemed likely to accept a few weeks ago. Republican demands for even more have led Reid to complain about trying to kick a field goal through a moving target.

But Republican Boehner may have the most to lose: He is balancing demands for more spending cuts from "tea party"-inspired colleagues, including many Republican freshmen, against his need to create a workable template for even more consequential dealings ahead - over raising the debt limit and passing a 2012 budget.

Key, as always these days, will be the reaction of independent voters. Most of these swing voters want the warring parties in Washington to compromise, even if it is on an imperfect budget deal, rather than allow the government to shut down, according to a recent national opinion survey by the Pew Research Center.

But the large class of conservative Republicans that took office this year, vowing to cut government, is pushing GOP leaders to shrink government in even more dramatic fashion. That's similar to what happened in 1995, when Republicans led by House Speaker Newt Gingrich took charge after decades of Democratic control.

Steve Elmendorf, then adviser to House Democratic leader Richard Gephardt, says if there's another shutdown, the public will blame Congress - and congressional Republicans especially - rather than Obama.

"The message he has to send is: I am doing everything I can to get a deal and these (Republicans) won't take yes for an answer," Elmendorf said.

But a former Gingrich adviser sees little comparison between then and now. "Boehner isn't Gingrich, which is a good thing, and Obama isn't (Bill) Clinton, which, for Democrats, is a bad thing," said Rich Galen, who was brought in to help Gingrich at the height of the '96 shutdown, which closed parts of the federal government for almost three weeks.

Independent pollster Andrew Kohut agrees that 1995 was different. Polling ahead of the shutdown suggested that Republicans would be considered the culprits if budget talks broke down, and they were. Clinton not only succeeded in dodging blame, "people came to have a much more positive view of him relative to the Republicans" and it helped boost him to re-election the next year.

Obama is in a more favorable position, by comparison, but he also "doesn't have the advantage Clinton had." Obama is "dealing with an opposition that isn't as poorly regarded" as the Gingrich-led Republicans, Kohut said.

Obama's personal engagement in attempting to break the impasse has served to counter a line of criticism - from Republicans and some Democrats - that he has been too aloof and uninvolved in the budget crisis, as in other issues. Repeatedly, over the last three days, he's appeared on television to criticize Congress' inability to resolve the issue and position himself as the more mature partner in the talks.

In the end, though, failure to avert a shutdown poses "risk for both sides," said Kohut, and could lead to any number of possible outcomes. The public could take the side of one party over the other, or "they may throw their hands up in disgust and say, 'Look at what a mess this is."'

---

(c) 2011, Tribune Co.

Distributed by McClatchy-Tribune Information Services.