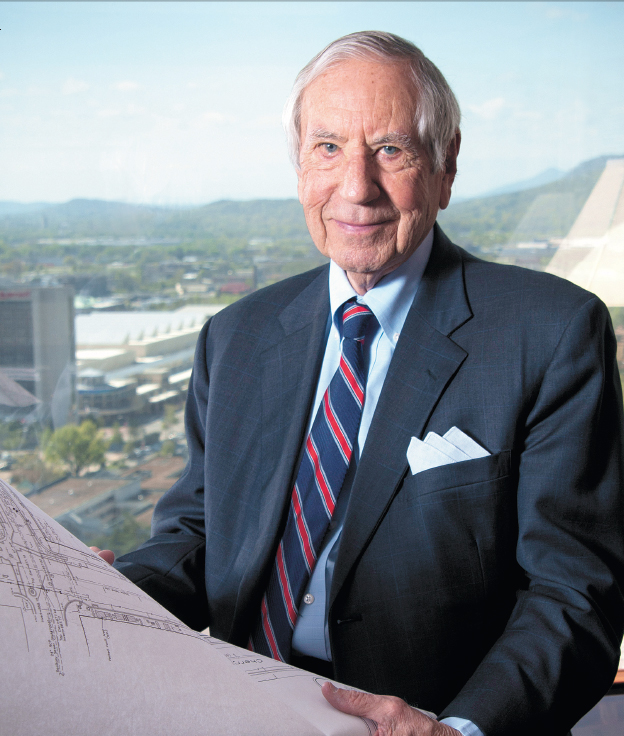

"I really should have been a cowboy," says James C. Berry - the 80-year-old Chairman and CEO of Republic Parking System, Inc. and owner of a commercial real estate business, the Jim Berry Company. He has retreated from his 20th floor corner office -with its panorama Lookout Mountain view, buffed cherry desk and lampshade with a price tag dangling inside - to an alcove secreted behind a paneled pocket door.

This paper-strewn "man cave" is Berry's command center, the inner sanctum. The furniture is beige; the blinds closed. A bag of Extra Value Intense Dark Ghirardelli chocolates sits next to a flashing, multi-decked phone. There is no cell phone, no computer - his secretary prints out his important emails.

Surrounded by stacks of documents, a photo of his grandson and a decades-old picture of his daughter standing in Daddy's shoes, the most powerful parking player in the country talks about his dreams.

"I stayed at home yesterday and - quote - rode the range in my Jeep Cherokee," says Berry. He owns a 400-plusacre farm called "The Last Frontier," near Birchwood, a 45-minute drive and 26 miles away. "But civilization's beginning to catch up with me. People are moving out to the country, and it's beginning to annoy me. I like to be where it's free, where the deer and the buffalo roam - I like what I call 'elbow room.'"

For 60 years, Berry has made a fortune in "elbow room." A hot commodity in post-World War II, Berry caught a ride in the parking industry's turbocharged machine. As the world became ever more car-loving and crowded, he struck gold in black tar and asphalt, mining crowded spaces stuffed with thousands of people desperately seeking spots to stow an SUV. Berry's Air Terminal Parking Company began as any small business would, with an educated risk, a sales route, a carefully targeted clientele. Today, his Republic Parking Systems, Inc. is one of the largest privately held parking management services companies in the country, with revenues of $360 million a year and about 2,600 employees.

The company's 60 on-site airport contracts range from Anchorage, Alaska to St. Petersburg, Florida. The company owns or manages more than 400 United Stares locations and multiple lots in San Salvador, El Salvador, and Santiago, Chile. The eponymous Jim Berry Co. also leases and manages 27 properties in Hamilton County, both privately and publicly owned, valued at perhaps $20 million. Recently, the company has been buying more downtown land, including the prominent Chestnut Tower at Chestnut and Sixth streets and Blue Cross/Blue Shield of Tennessee's former home, The Hub building at Seventh and Broad streets.

Berry also serves as vice chairman of Chattanooga's prominent development group, the River City Company. Governor Ned McWherter named him an Outstanding Tennessean in 1991. And, in 1999, Berry was the first to be inducted into the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga's College of Business Entrepreneurship Hall of Fame.

"Jim Berry is a veteran of the industry - and a visionary," says International Parking Institute Executive Director Shawn Conrad. An old friend, Chattanooga State Community College President Jim Catanzaro calls him "a hard-driving businessman who is exceptionally kind and caring." But a cowboy? "Yes," laughs Catanzaro. "He's a free spirit. He doesn't let obstacles get in the way - he just rides on past them."

PERFECTLY STRAIGHT

Berry's childhood stories reveal a hard edge, a tight discipline. "My parents were a bit perfectionistic," he says. "In the field, Dad wanted the rows to be perfectly straight. He always said 'do the best you can and do it right.'" His father, a Mormon, was a sharecropper - though he saved enough to buy the family a 40-acre farm in Chickasaw County, Miss. His mother, a Baptist, worked on the farm and also as a seamstress.

After high school, Draughton's Business School convinced him to move to Memphis with promises of classes, a room and a job. Berry got the bunk and the courses, but not the job. He canvassed

downtown's shoe stores, candy shops and jewelry marts until, on Oct. 1, 1949, the Allright Parking Company hired him to park cars.

Months later, Allright was beginning to feel all wrong. Morning classes were followed by 10-hour shifts, six days a week. Sleepless and stressed, Berry turned in his notice. But his boss took him aside.

Skilled, ambitious workers such as Berry were rare in this infant industry, said the boss. "He thought it would be wise to go into parking at this time," recalls Berry. "So I said I'd try it. If it didn't work out, I could always go back to school."

SCENIC CITY DREAMING

In May, 1951, Berry became Allright Parking's Chattanooga city manager. His first contract was with Provident Home Life Insurance Company (now Unum), which had bought and razed a block of houses. Many older buildings were demolished to make room for ever-larger Fords, Buicks and Caddies. "People said to me 'You want to tear my buildings down?'" says Berry. "But when I told them how much revenue they'd make, they agreed to do it."

At the time, parking had an "unsavory" image. "I struggled for many years with the question of who gets the most respect, garbage collectors or parking lot companies," jokes Berry. Unregulated, unprofessional, disorganized, Berry began to establish order.

"It put a strain on the rest of us, but I couldn't have someone work all day in a dirty uniform," says Berry. "So if someone showed up in a dirty uniform, or unshaved, I sent them home."

Ten years later, Berry was Allright's Southeast regional manager, working in about 15 locations. He became a vice president when the company went public in 1962. He soon wearied of estimating quarterly income and earnings for Wall Street stockbrokers who, he felt, couldn't care less about the business. "At that time, I realized I'm not cut out to be an executive in a publicly owned company," says Berry.

On January 1, 1966, he launched Air Terminal Parking, a three-person operation. He made bi-weekly loops through his targeted cities: Greenville, Columbia and Charleston, S.C., Savannah, Ga., Daytona and Tallahassee, Fla., Mobile and Montgomery, Ala., Rome, Ga. "I called it chasing rainbows," he says.

Six months later, Charleston, S.C., was on board. All except Montgomery eventually signed his contracts. "I was playing the odds," he says, smiling. "I never thought I'd get 8 out of 9." From the beginning, he ruled out such Gotham Cities as Atlanta, New Orleans, Chicago and San Francisco. "They were too political," says Berry. "It's not all dollars and cents - if I can't enjoy my work, why bother?"

When critics complained about high rates, he crafted this reasonable response - there is no such thing as free parking. "People have always resented paying to park, it's a natural reaction," he adds. A parking lot is as valuable as the buildings around it, even though it is bare and has no improvements, "It costs money to own it," he explains. "The owners are entitled to a return on their investment."

In 1982, he owned three companies: Hospital Parking Management Co., Air Terminal Parking and ParkRite. To simplify, he formed Republic Parking Systems, Inc, a name he felt "implied stability, financial strength and unity of purpose."

But he hadn't checked Webster's Dictionary. When he looked it up, he found it meant "a group of individuals dedicated to a common cause." "So I was lucky, because that's exactly what we were," says Berry, "we were a great team."

PARKING TO PASTIMES

After sixty years in pavement, Berry is putting up paradise. Last winter, he and his wife received the Chattanooga State Community College President's Award for Excellence in Philanthropy. The Berrys donated finishings and furnishings for two lunchrooms and the 135-seat Berry Auditorium in the Health Sciences Center. They declined to publicly state the amount of the gift. "My life touches so many aspects of this community," says Berry, "I feel good about being able to give something back."

Landscapes from the Berry farm will soon wrap around the walls, says Catanzaro, creating a 360-degree feeling of the outdoors. "It will be the capstone of his contribution," says Catanzaro. "Everyone in the auditorium will be enveloped by the wonderful environment he has on his property."

But in his white-walled "cubicle," as he refers to it, the parking czar reconsiders his cowboy dreams. "I never knew the anguish of having to choose a career," says Berry. "I grew up during the Depression. We simply worked hard for the things we needed."

At 80, he has begun to reflect on the roads not taken. "In my next life," he decides, "I will be a landscape architect - not for parks, for huge tracts of land, 100 acres and up - because I like to get in my Jeep Cherokee and ride out to 'The Last Frontier' and use my imagination as to what a particular area could look like if I planted trees here."