In 1984, rock climber Rob Robinson had questions.

Not "Should I tie a double bowline or a figure-eight follow-through?" kind of questions, but philosophical and logistical, game-changing questions.

He had just discovered a colossal hunk of sandstone in Prentice Cooper State Forest that he knew had epic climbing potential. "Nobody had even fathomed what was here," says Robinson while reflecting on the find.

But as he stared at the gray and tan rock face that would come be known as the Tennessee Wall, questions kept bubbling up. Should he tell other climbers or keep it to himself? Would the state allow climbing there? How would climbers get and keep access to the wall?

In 2007, climbers faced those same questions in an area near Soddy-Daisy known as Deep Creek and after years of hard work and innovative problem solving they believe access to the crags at Deep Creek represents the same kind of paradigm shift as Robinson's historic find.

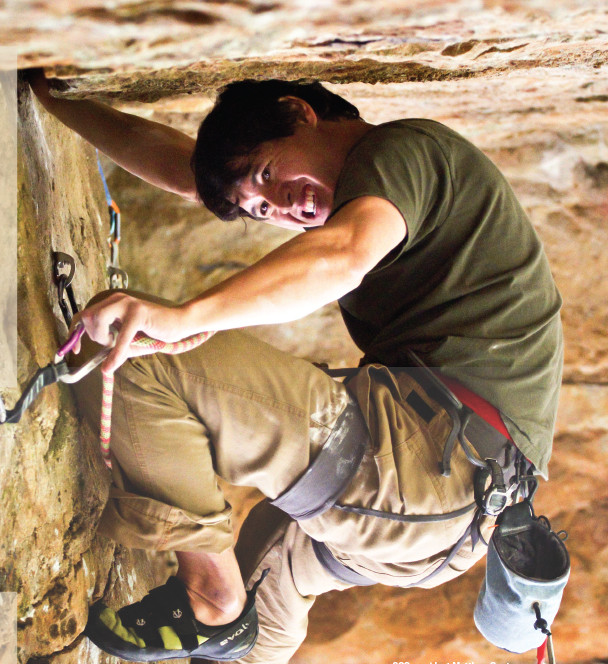

Unlike Chattanooga-area kayakers or hikers who have hundreds of miles of publicly accessible rivers and trails, the cliffs and crags making the region a mecca for rock climbing and bouldering frequently aren't open to the public. "If you find a cliff it's most likely on private land," says Cody Averbeck, a 24-year-old Signal Mountain climber.

And that fact, climbers say, makes the rock faces at newly accessible Deep Creek all the more important. The new climbing area is a forested sandstone gorge west of Soddy-Daisy, near where picturesque Deep Creek and Big Soddy Creek join. The 80-foot cliffs that have climbers drooling are located on state property along the Cumberland Trail recreation corridor, only a short walk from road access.

Robinson calls the new access to Deep Creek "an incredible thing," describing the crags within as "one more diamond in the South's sandstone crown." But for Averbeck, who plans to build a house within shouting distance of the trailhead, getting access to the rocks has been a tougher challenge than any of the 5.12 routes along the sandstone.

The short walk from the gravel road to the state land goes right through private property.

And without a public link or permission from the landowner to pass through, climbers faced a 4- or 5-mile hike from another Cumberland Trail trailhead to get to the crags.

When Averbeck and others contacted the landowner he gave a handful of climbers permission to pass through. But it quickly became apparent they needed a more permanent corridor and the owner mentioned he wouldn't mind selling some of the property. "We were like, we know what we have to do, we just have to figure out a way to do it," Averbeck says.

After a fundraising campaign, Averbeck and fellow climber Trevor Childress bought 38 acres of property, then gave space for a trailhead and pathway to the Southern Climbers Coalition. In doing so, they may have changed the way climbers think about access to cliffs in the future.

Matthew Gant, president of the Southern Climbers Coalition, says the arrangement, which involves a climber management plan and coordination with the Cumberland Trail Association and other groups, is unique in the region and maybe the country. Negotiations are proceeding with the groups to develop an agreement that establishes a benefit to the state of Tennessee while helping to also promote a positive recreational resource. "It represents a partnership with climbers and the state, but also with a lot of other partners," he says.

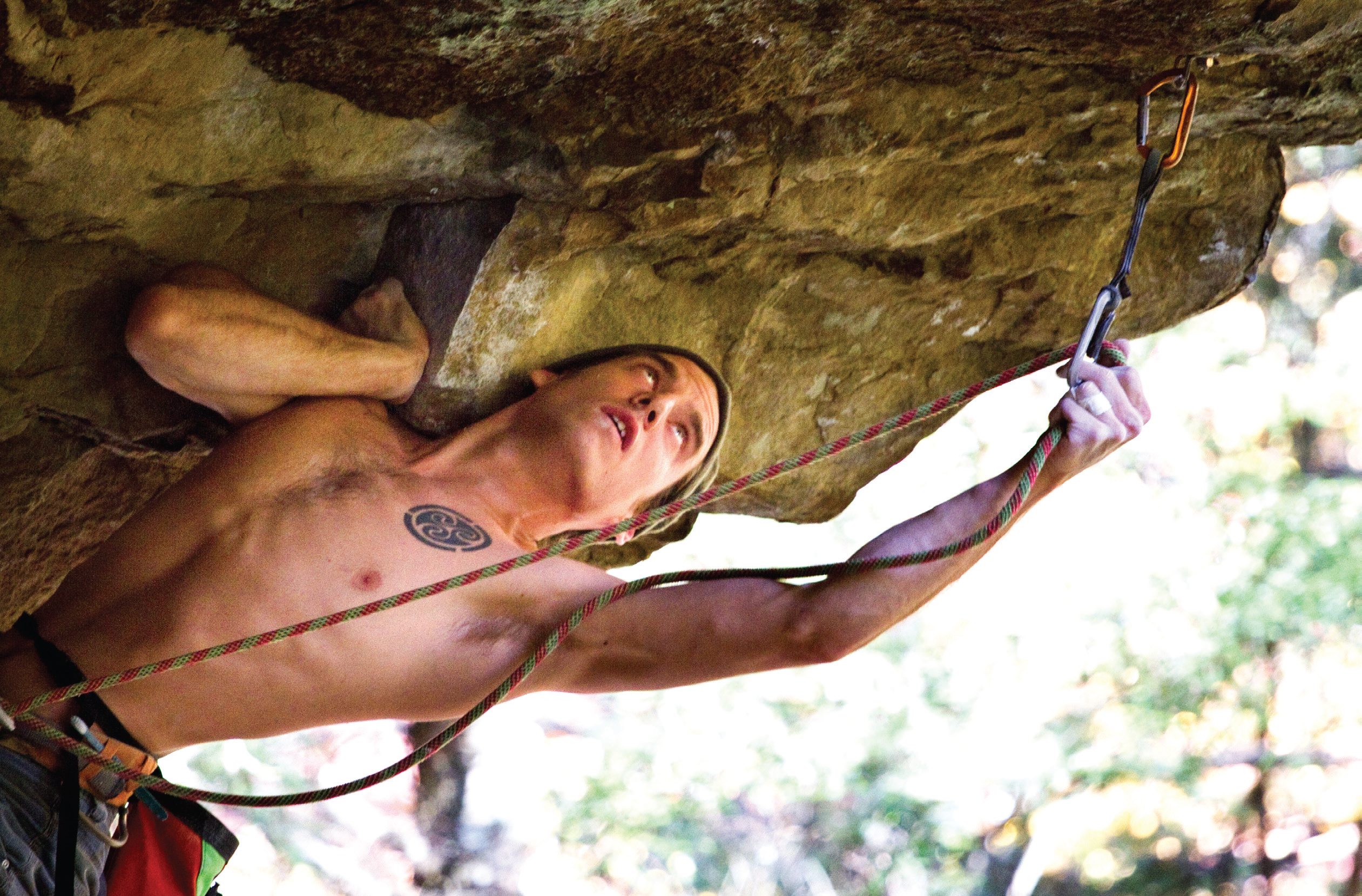

With good reason. Over the years climbers have had to be creative just to get to the rocks. Some climbing areas, like Robinson's Tennessee Wall, are on state property. The T-Wall is part of Prentice Cooper State Forest, which has long-established guidelines allowing many forms of recreation including climbing. Similarly, the climbing area at Foster Falls is jointly owned by the TVA and the state and has liberal recreation allowances. But many cliffs are on property owned by timber companies, private individuals and even golf courses. "Everything is privately owned around here. You have to like sneak to find new stuff," laments Chattanooga climber Paul Whicker, wearing a tie-dye Appalachian Trail shirt while climbing at Deep Creek.

Averbeck recalls one encounter with a landowner on a nearby 400-acre tract. The owner was not happy to discover climbers on his sandstone. "He was mad as hell," the Sewanee graduate remembers.

But after apologizing for trespassing, Averbeck struck up a conversation with the man and learned some of his anger came from thieves that had been poaching Indian artifacts from the property. After explaining why the climbers liked the formations, Averbeck took a gamble and offered to keep an eye out for artifact hunters and report any disturbances. The man's demeanor changed and he invited them back. "We're the informal caretaker of his property now," Averbeck says proudly.

More formal deals have also been struck. Before 2004, climbers had been sneaking into a bouldering area known as Little Rock City near Montlake Golf Course not far from Deep Creek. But through ongoing discussions, the climbing coalition has been able to secure access to the area. Now climbers even have their own parking spaces and hold a major part of the Triple Crown Bouldering Series there.

In 2005, the SCC negotiated access to the Castle Rock formation near Foster Falls. The group leases the half-mile of cliff line and hiking access trails from two landowners for $1,500 per year. In 2009, the coalition reached an agreement to get access to Yellow Bluff, a crag near Huntsville, Ala., that gained notoriety for its challenging routes in the 1980s before property owners closed it to climbers for 20 years.

But atat Deep Creek, owning the property was just the beginning. Neighboring property owners were concerned about everything from traffic and trash to potential drug use from their new neighbor's guests. Driving to the trailhead there are at least six varieties of No Tresspassing or Keep Out signs along the dirt road and two more posted along the trail.

Averbeck and Childress initially wanted to build a campground for climbers, which meant going through a hearing at the Chattanooga-Hamilton County Regional Planning Agency for a special-use permit. Minutes from their Feb. 14 hearing show 17 neighbors signed a petition against the campground, an idea that Averbeck says he has since completely abandoned.

A letter submitted to the agency by some of the area neighbors sums up the opposing viewpoints well: "The Southeastern Climbers Coalition is an organization with thousands of members with one mission: find, secure and preserve climbing areas for future generations. The residents of Old Hot Water Road also have a mission: It is to protect and preserve our community for our homeowners, children and future generations."

Averbeck says he regrets not reaching out to the neighbors first, but history shows it's not the first time climbers and property owners have had diverging interests.

"There are a lot of areas that do have access issues," says Robinson. He wrote an article in Rock and Ice magazine more than 20 years ago discussing the need for climbers to build bridges with local landowners and the non-climbing public. "It wasn't quite as big of an issue when there were only a few climbers," explains Robinson, who remembers when there were only about six climbers in the city. "Looking to the future, we saw there were going to be problems."

Other climbers are starting to grow concerned over the same things. Changing his shoes after climbing the No Entry Gentry route at Deep Creek, Tim Hinck says the number of climbers around Chattanooga seems to double every year. And large numbers of even the cleanest and quietest climbers have an impact. Hinck, who has been climbing around Chattanooga for 12 years, says he started climbing at Deep Creek when there wasn't even a footpath along the base of Creek Wall. "Now you could almost drive a car down it," he says.

Hinck and his buddy Whicker climbed several of the creek's routes one beautiful October Saturday. Fifty feet away, three climbers from Atlanta scaled a rock face and another local couple belayed each other 300 feet away in the other direction. That's not a crowd, but there's always that concern.

Hinck shared horror stories of the Red River Gorge in Eastern Kentucky, a national climbing destination that some say has become too popular. Rangers and volunteers frequently have to patrol through the gorge's climbing area loading up bags of refuse. Some crags at the gorge have even been closed to give the area a chance to recover.

Deep Creek doesn't have nearly the usage issues of the Red River, Hinck says. He still finds plenty of places for solitude. But immediately after singing praises about Deep Creek, Hinck thought about the consequences and jokingly backed off of his accolades. "Don't put that in the article," he jokes. "Tell them it's shitty."

Averbeck says managing Deep Creek's popularity is going to be a challenge, but there are several limiting factors that should help control the growth. For starters, from November to June the water table is high and seepage makes the Deep Creek cliffs slippery and unusable for climbers.

Additionally, the SCC parking lot only has 26 spaces and there are no plans to add on. On top of that, climbers must visit seclimbers.org/deep-creek and agree to terms before they get the code to unlock the gate.

"We're not out here to create a theme park," says Averbeck. "We're here to balance all of these moving parts." Stewardship, Robinson says, is a hugely important second step for climbers once they do get access. He's been encouraging climbers to clean up trash, maintain trails and find other ways to improve the areas where they are allowed to climb.

"Climbers I think always have to look for positive things they can do," Robinson says. "They've got to demonstrate that they're responsible and accountable because it opens doors for more and more climbing resources."