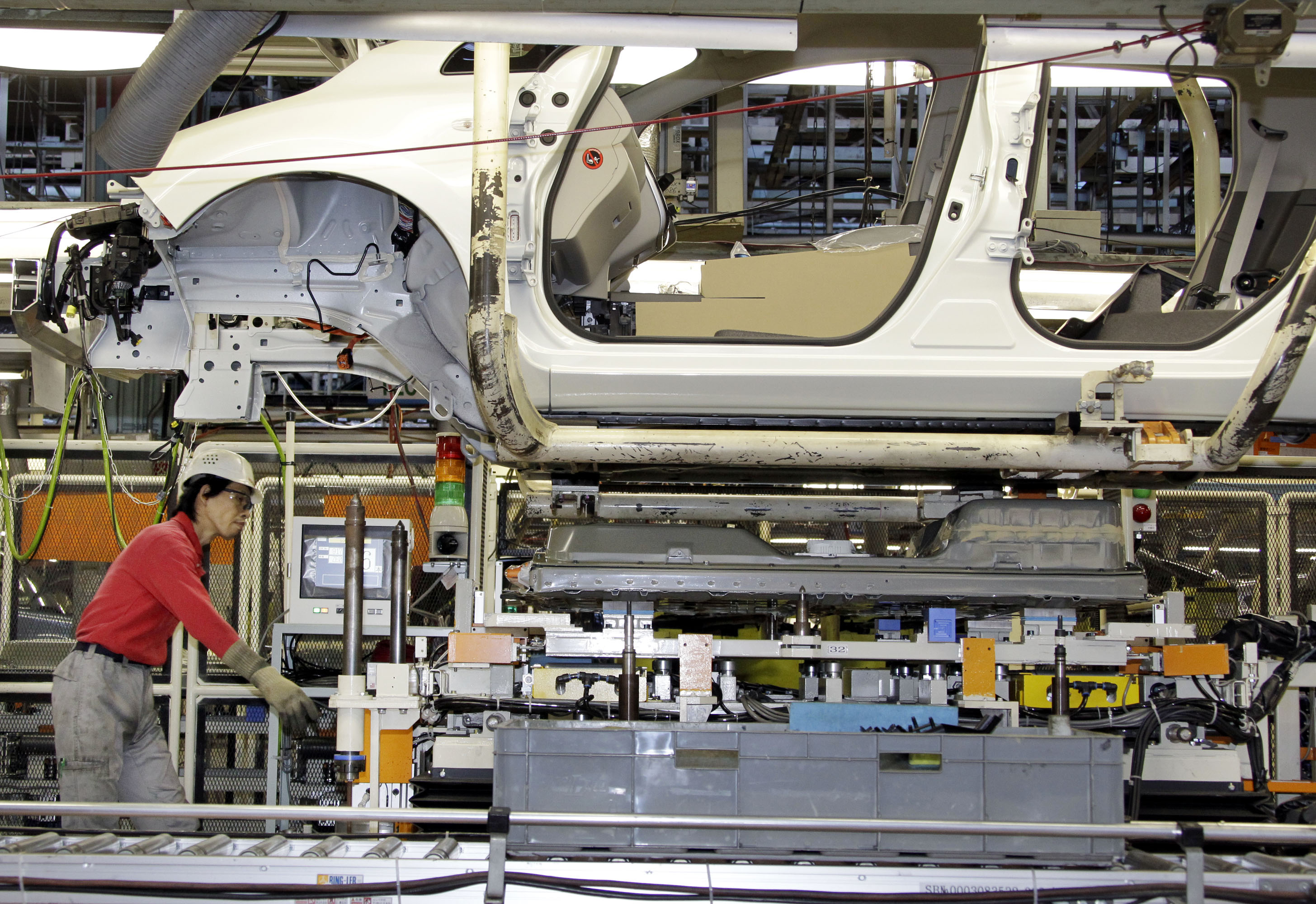

An assembly line worker puts a battery, seen right under the body, to a Nissan Motor Co.'s electric vehicle Leaf at the Japanese automaker's Oppama plant in Yokosuka near Tokyo. Nissan resumed auto and parts production at more Japanese factories last week, but it may be several months before inventories and other elements of the country's auto industry return to normal.(AP Photo/Koji Sasahara, file)

An assembly line worker puts a battery, seen right under the body, to a Nissan Motor Co.'s electric vehicle Leaf at the Japanese automaker's Oppama plant in Yokosuka near Tokyo. Nissan resumed auto and parts production at more Japanese factories last week, but it may be several months before inventories and other elements of the country's auto industry return to normal.(AP Photo/Koji Sasahara, file)By PAUL WISEMAN

AP Economics Writer

WASHINGTON - The Japanese economy has been staggered by an earthquake, a tsunami and a nuclear crisis. But history suggests it will bounce back with no lasting damage.

Wealthier countries with stable government institutions are especially suited to benefit from reconstruction after a natural disaster. So are countries with vast international trade and those that can easily raise money.

Japan falls into all those categories. Its own Kobe area recovered unusually quickly from a 1995 earthquake, for example. And researchers say the May 2008 quake in the Sichuan province of China led to stronger growth that same year.

The World Bank estimates Japan will spend up to five years rebuilding from the March 11 disaster. Reconstruction projects contribute to growth by putting people to work. Economies also benefit as damaged roads, ports, buildings and equipment are replaced. And typically, they are replaced with more efficient structures that help expand the nation's productivity and growth.

"We expect growth in Japan will pick up as reconstruction efforts accelerate," Vikram Nehur, the World Bank's chief economist for East Asia, said Monday.

In the aftermath of the nuclear crisis, Japan also stands to benefit from research and development projects designed to find alternative energy and reduce its dependence on nuclear energy and imported oil, says Reinhard Mechler, an economist at Austria's International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Researchers have documented that natural disasters, for all the death and destruction they leave, cause surprisingly little lasting economic damage.

A report last year by the Inter-American Development Bank found that natural disasters tend to cause long-term economic damage only when they trigger political upheaval. Iran and Nicaragua, for instance, were crippled economically by 1979 revolutions that followed killer earthquakes.

Otherwise, economies usually respond with long-term resilience after natural calamities.

Chinese government researchers have calculated that the Sichuan earthquake and the massive reconstruction effort that followed added to China's sizzling 9.6 percent growth in 2008.

And consider the deadly earthquake that hit Kobe, Japan, in January 1995. Experts predicted the area would need a decade to recover. Instead, Kobe's manufacturers were producing at 98 percent of pre-quake levels within a year and three months, according to a study by the late Purdue University economist George Horwich. About four in five retail shops, including all department stores, were open in a year and a half.

Even with the devastation in Kobe, Japan's economic growth more than doubled from 1994 to 1995.

Similarly, Hurricane Katrina devastated coastal Louisiana and Mississippi in 2005 but "didn't puncture investment or growth in the rest of the country," says Robert Shapiro, a former Commerce Department official and chairman of the economic consulting firm Sonecon.

And the reconstructions that followed the 1989 Northern California quake and the 1994 Southern California quake are widely believed to have helped the California economy.

Countries without deep financial reserves, trade relationships or skilled work forces are much less likely to benefit from rebuilding programs. Impoverished Haiti, for instance, lacked the resources to handle the aftermath of a deadly quake last year - even with help pouring in from overseas.

Japan, by contrast, has the institutions to handle a massive reconstruction effort, says Mark Skidmore, a Michigan State University economist. "They have high human capital," he says. "They have pretty darn good institutions."

And "if you've got trade, you've got ports and other distribution resources" that speed delivery of relief supplies and construction material to disaster zones.

Even in the developing world, the economic damage is typically short-lived. A poor country's economy typically shrinks in the first year after a calamity, then bounces back as investments pour in and money moves around, Mechler says.

Sonecon's Shapiro raises the concern that Japan won't prove as resilient this time as it was after the Kobe quake in '95. This month's quake damaged power plants, leaving communities with crippling electricity shortages. Shapiro says the threat of radiation leaks from a nuclear power plant damaged in the quake also could paralyze the economy. And the Tokyo government is deep in debt. Some question whether it could finance a rebuilding effort that is expected to cost more than $200 billion.

Others point out that the Japanese government can raise money by selling bonds to the Japanese public, which has a high savings rate. The United States, by contrast, relies heavily on foreign governments and investors to finance massive government deficits.

In its report Monday, the World Bank estimated that Japan's disaster would reduce the country's growth by up to 0.5 percentage points this year. But it also says the slowdown won't last much beyond mid-year.