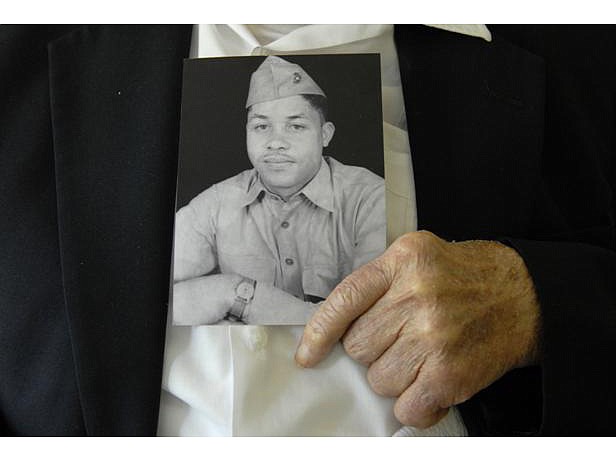

Willie Hazelrig, a WWII veteran who served with the Montford Marines, the first black Marine unit, talks about his experiences during the war. Saturday, Hazelrig will be awarded the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest civilian honor, from the Marine Corps and will receive a letter from the president recognizing his service.

Willie Hazelrig, a WWII veteran who served with the Montford Marines, the first black Marine unit, talks about his experiences during the war. Saturday, Hazelrig will be awarded the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest civilian honor, from the Marine Corps and will receive a letter from the president recognizing his service.LAFAYETTE, Ga. - When Willie Haslerig was drafted on May 20, 1945, he'd never heard of the U.S. Marines.

Today his brothers-in-arms will honor him for being among the first black men to enter the military branch's ranks.

As World War II raged overseas in the 1940s, Haslerig worked on his father's farm near Chickamauga, Ga. A young black man in the pre-Civil Rights era South, he had seen his family home burn in a racially-motivated attack, he said.

The borders of the segregated world where Haslerig lived didn't end at the Mason-Dixon line. Until an order by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1942, the Marine Corps was an all-white force that didn't want blacks.

The first wave of black men recruited or drafted into the Marines became known as the Montford Point Marines, named for their segregated boot camp in North Carolina.

On June 27 Congress honored those Marines with the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest civilian honor given by Congress. Documents show that there could be 420 Montford Point Marines still living. According to news reports, 370 were present at the Congressional ceremony.

Marines from the Chattanooga-based reserve unit and local officials are scheduled to present Haslerig with the medal this afternoon at Heritage Health Care, the nursing home where he lives.

A life change

Haslerig's farm job was deemed essential to the war effort and he was exempted from the draft the first few times. Then the Georgia state draft board took over and his exemptions ended.

The 23-year-old saw his record first stamped "Army" and later "Navy." When he arrived at the induction center for duty, he was told he and the other men were going to be Marines.

"I didn't know what a Marine was," Haslerig said.

He'd soon find out.

The Marine Corps didn't roll out the welcome mat for black recruits sent its way. Rather than train with the white troops in San Diego, Calif. ,or Parris Island, S.C., the men were shuffled off to Montford Point, N.C.

From 1942 until 1949 as many as 20,000 black Marines went through boot camp there.

On his first day, a hard-jawed drill instructor got in his face.

"What's your name?" Haslerig recalled the man yelling.

"Willie Haselrig," he replied.

"Where are you from?" the drill instructor yelled.

"Walker County, Ga." he said.

"Spell it," the man yelled.

And before he could open his mouth the drill instructor had knocked him to the ground.

"It was awful rough," the now 90-year-old man recalls.

After boot camp he and 140 other black Marines traveled by train from North Carolina to Meridian, Miss., to ship overseas.

He was in charge of the men. As the train pulled into the station, one of the Marines hopped off, kissed two white women and jumped back into the crowd.

Military police escorting the men called the state militia, Haslerig said.

He knew who the man was and ordered all of the Marines to put on their helmets and packs.

"We all looked the same with helmets and packs," he said.

The MPs couldn't find the man.

"I don't know what would have happened to him," Haslerig said.

Returning home

Not all of his time in the Marines was bad. He landed an administrative job after boot camp and shipped to Hawaii soon afterward. The war ended and he returned with troops in a mixed unit, blacks and whites, coming home from overseas.

But some things still hadn't changed.

The first command on reaching a U.S. port was to separate, whites this way, blacks that way, he recalled.

Like many of his generation, Haslerig returned home, went to work, raised children. He spent 14 months in the Marines and the rest of his life in this area.

Three of his children - Carol Newman, Delores Hodges and Joyce Harrison - marvel at their dad's service.

"I'm just so proud of him," Hodges said Friday.

"In spite of everything, he's an optimist," Harrison said.

Newman said their father is a strong reminder of the struggles minorities have faced and overcome. His life serves as a lesson for members of their family and the black community.

In his own words, Haslerig says it best: "Use every obstacle that you get to as a stepping stone. Any obstacle that I run into, I try to use that to climb a little higher."