By MICHAEL BARBARO and ASHLEY PARKER

c.2012 New York Times News Service

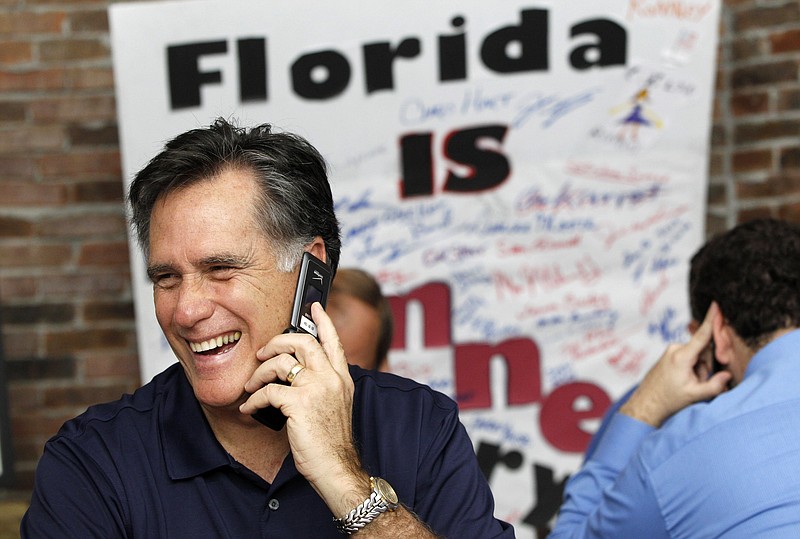

With his resounding victory over Newt Gingrich in Florida on Tuesday, Mitt Romney showed a worried Republican base a side of himself that it has both longed for and feared that he lacked: the agile political street fighter, willing to mock, scold and ultimately eviscerate his opponent.

But if he has quelled doubts about his toughness, he also emerges from the Florida free-for-all and the three contests that preceded it carrying heavy new baggage.

Romney was savaged by Gingrich over his record at Bain Capital, softening him up for the coming Democratic effort to portray him as a heartless capitalist happy to fire people to enrich himself. His release of his tax returns, complete with details about a Swiss bank account, provided concrete new facts for opponents seeking to cast him as out of touch with ordinary Americans.

And the very trait that propelled him in Florida - a willingness to descend into the muck and run a relentlessly negative campaign - distracted from his economic-themed argument against President Barack Obama while deepening his rift with some populist conservatives. Should Gingrich remain a viable enough candidate to stay in the race through the summer, Romney could be forced to maintain an edge that could undermine his appeal among moderate and independent voters - groups whose views of him, polls suggest, appear to have been harmed by the Florida melee.

"There are questions about his wealth and Bain, but he has not become an intensely polarizing figure yet," said Alex Castellanos, a Republican strategist who worked on Romney's presidential campaign in 2008. "The question is, will he become that?"

Romney himself seemed sensitive to the perception that his campaign has become locked in a bitter - B and counterproductive - war of words with his leading Republican rival.

"I would like to spend more of our time focusing on President Obama," he said in Tampa, Fla., on Tuesday as voting was under way. "That's ultimately what's going to be essential to taking back the White House."

His challenge is about to become even more complicated. As much as he would like to be punching and counterpunching with Obama, he must still contend with Gingrich, who vowed Tuesday night to remain in what he described as a two-man nomination fight.

Romney faces a classic dilemma in presidential politics: Going negative is never an appealing option, but the alternative amounts to unilateral disarmament and a much higher likelihood of defeat, especially against a rival like Gingrich who has little to lose.

"In primary politics, short-term gains are what matters, because if you don't have the short-term gains, you won't be around long enough to deal with the long-term problems," said Peter A. Brown, assistant director of the Quinnipiac University Polling Institute.

Romney and his super PAC allies spent $15.4 million on television and radio advertising in Florida, three times what Gingrich and his supporters spent, in the most intensive assault of the Republican nominating contest: Overall, 92 percent of the ads from the candidates and outside groups were negative. In Florida, the outcome was what Romney needed - and possibly enough to all but eliminate Gingrich as a threat.

But if Romney has to engage in a long stretch of negative campaigning against Gingrich, the challenge will be to hit back hard enough that he does not leave himself exposed to another Gingrich comeback without undercutting his own image among voters.

A candidate who comes across as attacking too viciously and personally runs the risk of turning off all but the most partisan voters. It happened with Bob Dole on a number of occasions, most famously when he lost his temper during the 1988 presidential race, snapping that Vice President George Bush should "stop lying about my record." That moment haunted him throughout the campaign. That may be one reason that Romney, in the glow of his Florida victory, praised his three competitors and turned his attention to the president.

Romney has never been especially squeamish about negative advertising. As jarring as his campaign's tone seemed over the past 10 days, he has long history of resorting to such tactics. (The exception was 2008, when Romney bowed out relatively early in the primary season, without having faced the kind of scorched-earth matchup he has had with Gingrich.)

During his 2002 campaign for governor of Massachusetts, Romney ran biting television commercials that portrayed his Democratic rival, state treasurer Shannon O'Brien, as a basset hound asleep on the job as men walked off with bags of money. His poll numbers soon surged, and he pulled out an unexpected victory.

"He has learned along the way that this stuff works pretty well," said O'Brien, who called the ads inaccurate and unfair.

This time around, Romney has been responding to scathing assaults on him from Gingrich, who in turn has said he went negative because the super PAC supporting Romney had unfairly attacked him in Iowa. Determined not to lose in Florida as he did in South Carolina, Romney unleashed a wave of attacks on Gingrich's finances, ethics and even stability -B hammered repeatedly in TV commercials, conference calls, emails and speeches by the candidate himself - that helped stoke the image of Gingrich as an "erratic" and "unreliable" leader who.

The balance that Romney is trying to strike in his so-far effective campaign against GingrichB is the same one he has to strike if he ends up running against Obama, whose campaign aides have made clear that a general election campaign against him will be highly personal. B