PARKDALE, Ore. - People on the West Coast have counted on fish hatcheries for more than a century to help rebuild populations of salmon and steelhead decimated by overfishing, logging, mining, agriculture and hydroelectric dams, and bring them to a level where government would no longer need to regulate fisheries.

But hatcheries have thus far failed to resurrect wild fish runs. Evidence showing artificial breeding makes for weaker fish has mounted. And despite billions spent on significant habitat improvements for wild fish in recent decades, hatchery fish have come to dominate rivers.

Critics say over-reliance on costly breeding programs has led to a massive influx of artificially hatched salmon, masking the fact that wild populations are barely hanging on and nowhere close to being recovered. Recently touted record runs were made up mostly of hatchery fish, and scientists are concerned that hatchery fish could completely replace wild fish --though state and federal officials say they are working to address the problem.

Now, the practice of populating rivers with hatchery fish rather than making greater efforts to restore wild runs is facing a battery of court challenges in Oregon, California and Washington state.

The disputes illustrate a crucial tension in the Pacific Northwest, where salmon and steelhead are iconic fish -- of enormous cultural and nutritional significance to tribes, job creators for commercial fishermen and big draws for recreational anglers. Hatcheries also help meet legal obligations to provide fish while dams are in place and fulfill Native American treaty rights.

"We as a society have made conscious decisions to significantly alter habitat, and we also made commitments to people who utilize fish - tribes and non-Indians - that fish will be available," said Stuart Ellis, harvest biologist at the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission. "To the extent that hatchery programs may pose some sort of risk to remaining natural populations, you have to balance those risks with the promises that were made."

With 13 species of salmon and steelhead listed as endangered or threatened under the Endangered Species Act in the Columbia River basin, the government also has a legal obligation to restore wild runs. Court battles on just how to do that have been going on for years.

Environmentalists and many scientists argue the only way to bring back wild fish is to remove dams that produce the region's cheap power, but the government has ruled that out. The hatchery lawsuits are trying a different tack.

Last month, an Oregon judge ordered officials to do more to ensure hatchery fish do not stray into wild fish habitat and harm wild fish on the Sandy River, a Columbia River tributary. Lawsuits have been filed to limit or block the release of hatchery-raised fish into Oregon's McKenzie River and Washington's Elwha River.

And in California, a lawsuit recently resulted in a settlement requiring a hatchery on the Mad River to institute a genetic management plan to better protect wild salmon from hatchery fish. Another suit is still pending regarding the Trinity River hatchery in that state.

The impact of the lawsuits on other hatchery operations is unknown, but environmental groups say the Sandy River ruling sets an important precedent.

Courts could mandate hatcheries do less harm to wild runs, including releasing fewer artificially-bred fish into rivers, more monitoring and stronger barriers separating wild from hatchery stocks, said Bill Bakke, director of the Portland-based Native Fish Society, which filed the Sandy River suit. Such reforms, he said, could put wild fish on the road to recovery -- and benefit the fisheries.

"We need to maintain healthy and abundant wild populations not only for their own sake, but to be a supply of fish for hatchery production and to keep hatchery programs cost effective," Bakke said.

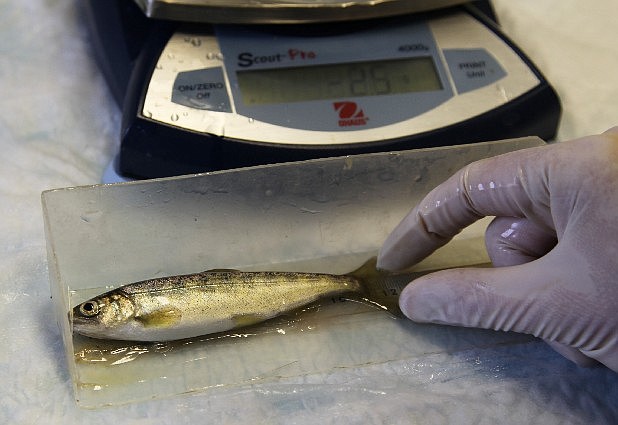

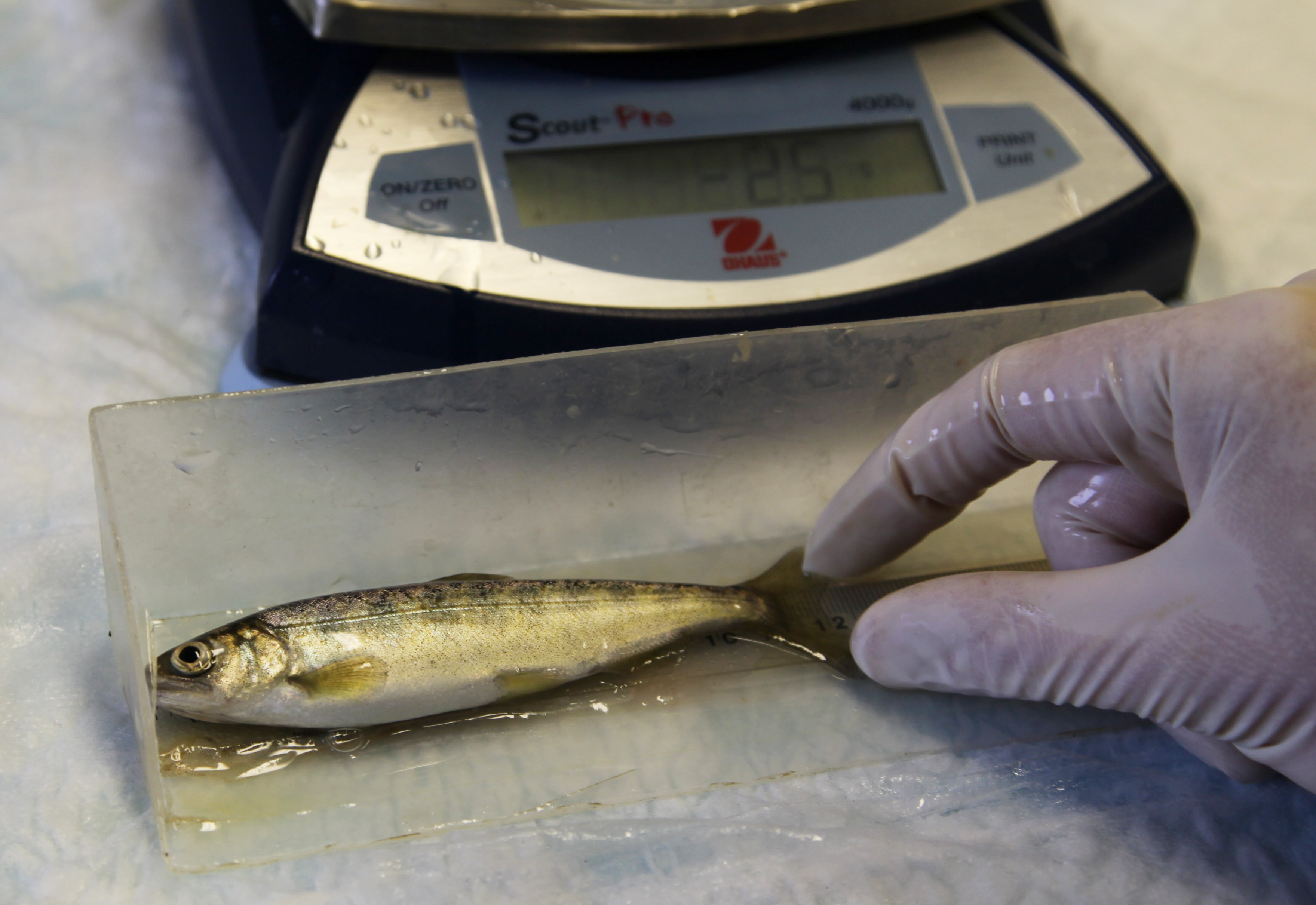

About 400 hatcheries operate throughout the West Coast today. In the Columbia River basin, about 180 hatchery programs breed millions of fish in plastic trays, transfer them to rearing "ponds," and then release them to join wild ones travelling down river to the Pacific Ocean, to later return to the same river to reproduce and die. Most hatcheries are devoted to turning out fish for fishermen to catch.

Over the past few decades, numerous studies have shown that breeding in captivity makes for fish that are less capable of producing offspring. Hatchery fish also out-compete wild fish for food as they inundate rivers and oceans. Their presence lowers the number of offspring produced by wild populations, disrupts local adaptations acquired over centuries, and leads to loss of genetic diversity.

Hatchery proponents acknowledge the risks of artificial propagation. They say reforms are already in the works. Many hatcheries now use native breeding stock. They also avoid mixing hatchery and wild fish on the spawning grounds. Other hatcheries have been scaled back or turned off.

But "much of the effort is to try to figure out ways to both maintain significant hatchery production and limit impacts to wild populations," said Mike Ford, conservation biology division director for NOAA Fisheries' Northwest Fisheries Science Center in Seattle.

Ford and other proponents say artificial breeding has benefits: it can bring back fish to rivers where they have been wiped out. That's already happening on the Hood River, where the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs and Oregon biologists have reared Chinook salmon for over two decades. Their population has increased, enough to re-establish limited fishing for the tribe and other fishermen.

But hatchery fish and their progeny now dominate the run, just as they do on the Snake River, where another tribal hatchery has vastly increased the numbers of returning fall Chinook salmon.

"If the only societal goal for salmon was conservation and recovery of wild populations," Ford said, "I think hatcheries would play a much more limited role than they do now."