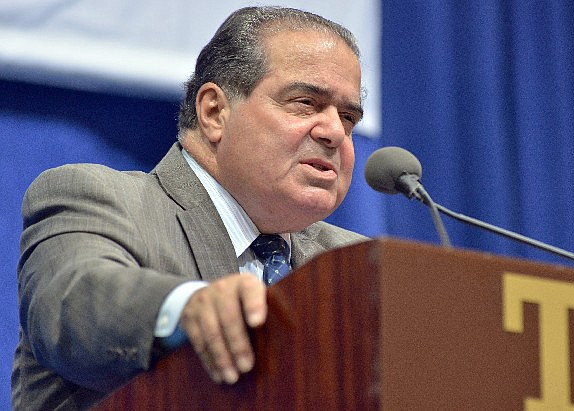

Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia speaks at Tufts University in Medford, Mass. At the Supreme Court, technology can be regarded as a necessary evil, and sometimes not even necessary. When they have something to say to each other in writing, the justices never do it by e-mail. And the court's historical society says the Supreme Court had no photocopying machine until 1969, a few years after Xerox had become a verb. Among those who think the Supreme Court will weigh in is Justice Antonin Scalia, who addressed the topic in July in a question-and-answer session with a technology group. Scalia said the elected branches of government are better situated to balance security needs and privacy protections.

Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia speaks at Tufts University in Medford, Mass. At the Supreme Court, technology can be regarded as a necessary evil, and sometimes not even necessary. When they have something to say to each other in writing, the justices never do it by e-mail. And the court's historical society says the Supreme Court had no photocopying machine until 1969, a few years after Xerox had become a verb. Among those who think the Supreme Court will weigh in is Justice Antonin Scalia, who addressed the topic in July in a question-and-answer session with a technology group. Scalia said the elected branches of government are better situated to balance security needs and privacy protections.WASHINGTON - At the Supreme Court, technology can be regarded as a necessary evil, and sometimes not even necessary.

When the justices have something to say to each other in writing, they never do it by email. Their courthouse didn't even have a photocopying machine until 1969, a few years after "Xerox" had become a verb.

So as the legal fight over the NSA's high-tech collection of telephone records moves through the court system, possibly en route to the Supreme Court, some justices already are on record as saying they should be wary about taking on major questions of technology and privacy.

As Justice Elena Kagan understated last summer, "The justices are not necessarily the most technologically sophisticated people."

The wariness shows up in rulings, too. When the court in 2010 upheld a police department's warrantless search of an officer's personal, sometimes sexually explicit messages on a government-owned pager, Justice Anthony Kennedy suggested caution. He wrote, "The judiciary risks error by elaborating too fully on the Fourth Amendment implications of emerging technology before its role in society has become clear."

Clear or not, the implications of technology are increasingly relevant. Constitutional protection against the prying eyes of government, without a judge's prior approval, is embodied in the Fourth Amendment's prohibition on unreasonable searches and seizures.

Last month, U.S. District Judge Richard Leon of Washington ruled that the NSA's phone-records collection program probably fails that Fourth Amendment test and is unconstitutional. Leon called the program "Orwellian" in scale.

The Obama administration has defended the program as an important tool in the fight against terrorism and is expected to appeal the ruling. Complicating matters, 11 days after Leon's ruling, U.S. District Judge William Pauley III of New York declared the NSA program legal in dismissing a lawsuit filed by the American Civil Liberties Union. In addition, legislation in Congress and possible administration changes could alter NSA surveillance and affect the court cases.

Still, many people expect the Supreme Court will have the final word on the program, especially if other appellate judges agree with Leon.

Among those who think the Supreme Court will weigh in is Justice Antonin Scalia, who addressed the topic in July in a question-and-answer session with a technology group. He didn't sound happy about the prospect of such a ruling. Scalia said the elected branches of government are better situated to balance security needs and privacy protections.

But he said that the Supreme Court took that power for itself in 1960s-era expansions of privacy rights, including prohibitions on wiretapping without a judge's approval.

"The consequence of that is that whether the NSA can do the stuff it's been doing ... which used to be a question for the people ... will now be resolved by the branch of government that knows the least about the issues in question, the branch that knows the least about the extent of the threat against which the wiretapping is directed," he said. Scalia repeatedly used the term "wiretap" in his comments, but indicated later that he was speaking more generally about NSA surveillance, including the collection of phone records.

In the police pager case, Scalia was part of an exchange with Chief Justice John Roberts that sounded almost like a comedy routine.

Roberts was questioning the lawyer for the officer whose messages were searched. He asked whether it was reasonable for the officer and others to assume that a third party, the pager service, was actually routing the messages from sender to recipient, much the way a phone company does with calls.

"I wouldn't think that. I thought, you know, you push a button, it goes right to the other thing," Roberts said.

Sitting to Roberts' right, Scalia chimed in, "You mean it doesn't go right to the other thing?"

They may have been playing for laughs, but the justices left the impression that day that they did not fully grasp what a pager is and how the process works, said Orin Kerr, a George Washington University law professor and expert on privacy and technology.

"It was embarrassing," said Kerr, who has urged courts to go slow and defer to elected officials in applying constitutional protections to privacy issues raised by new technologies.

Like Scalia, Justice Samuel Alito said he thinks Congress is better situated than the court to reconcile technology and modern-day expectations of privacy.

"New technology may provide increased convenience or security at the expense of privacy, and many people may find the trade-off worthwhile," Alito wrote in a 2012 opinion joined by three other justices. "And even if the public does not welcome the diminution of privacy that new technology entails, they may eventually reconcile themselves to this development as inevitable," he said in the case involving a GPS device that police attached to a car without a warrant.

He added: "On the other hand, concern about new intrusions on privacy may spur the enactment of legislation to protect against these intrusions."

Alone among her colleagues, Justice Sonia Sotomayor used the same case to suggest that it might be time for the court to revise its views on privacy, developed in the 1960s and '70s as they relate to the use of telephones and other devices where people voluntarily hand over information, but assume that those transactions are closely held.

"Perhaps, as Justice Alito notes, some people may find the 'trade-off' of privacy for convenience 'worthwhile,' or come to accept this 'diminution of privacy' as 'inevitable,' and perhaps not. I for one doubt that people would accept without complaint the warrantless disclosure to the government of a list of every website they had visited in the last week, or month, or year."

The justices themselves exercise plenty of care, whatever the reason. Kagan, speaking in Providence, R.I., last August, said that when the justices communicate with each other in writing, they write memos printed out on paper that looks like it came from the 19th century. Aides carry the documents from one justice's chambers to another's.

Television cameras remain barred from the courtroom, and some justices limit the use of tape recorders when they make public remarks.

Of course, the Supreme Court is asked frequently to set national rules on complicated topics about which the justices have imperfect knowledge.

It was Scalia who noted his inability to join some parts of Justice Clarence Thomas' majority opinion in a patent case in June dealing with molecular biology. "I am unable to affirm those details on my own knowledge or even my own belief," Scalia said in a brief separate opinion.